He stormed on to Death Row with his fists balled tight, a sneer on his face that was either a challenge or a deterrent. His wavy hair was spinning, too well-kept to have just fought someone, so if he wasn’t in trouble, then he must be looking for it. ‘Who the hell comes through the doors on Death Row inviting conflict with hardened killers?’ I thought. Not me. I arrived on Death Row the day before, and I was trying to go unnoticed. He was trouble alright, with his tattooed neck and gangster lean as he slung his sack of property on the top bunk with a thud. Young. Unruly. Someone to avoid. My judgment of him was just getting started when, unexpectedly, he turned and offered me a cigarette.

That was how I first came to know Eric Queen, it was upon our arrival on Death Row. Two young men trying to wrap our heads around the most terrifying thing to happen to a person. At least, that’s what receiving the death penalty was for me. Eric seemed too mad to give a damn, an anger that burned without direction. I should’ve been just as mad since I was there without cause. I’d taken a beating to my reputation at trial court with the lies and accusations. Maybe I thought playing nice would earn me a reprieve, when the truth was, I could have used some of Eric’s anger.

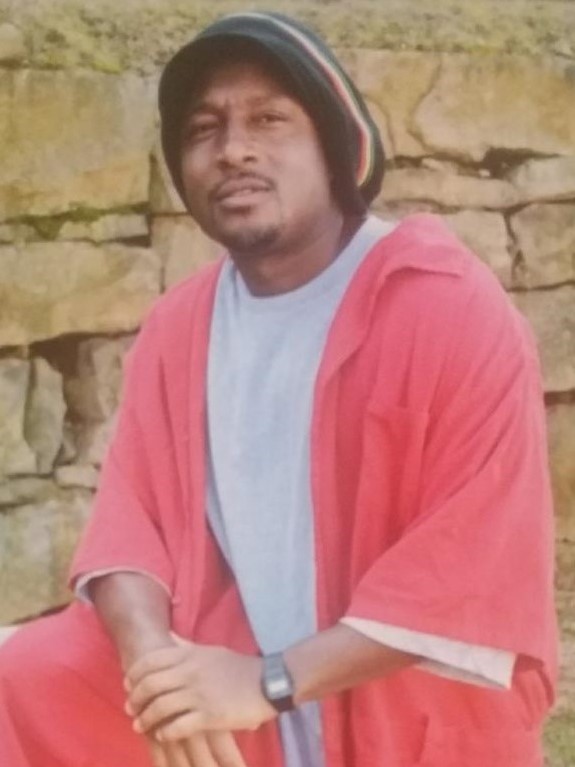

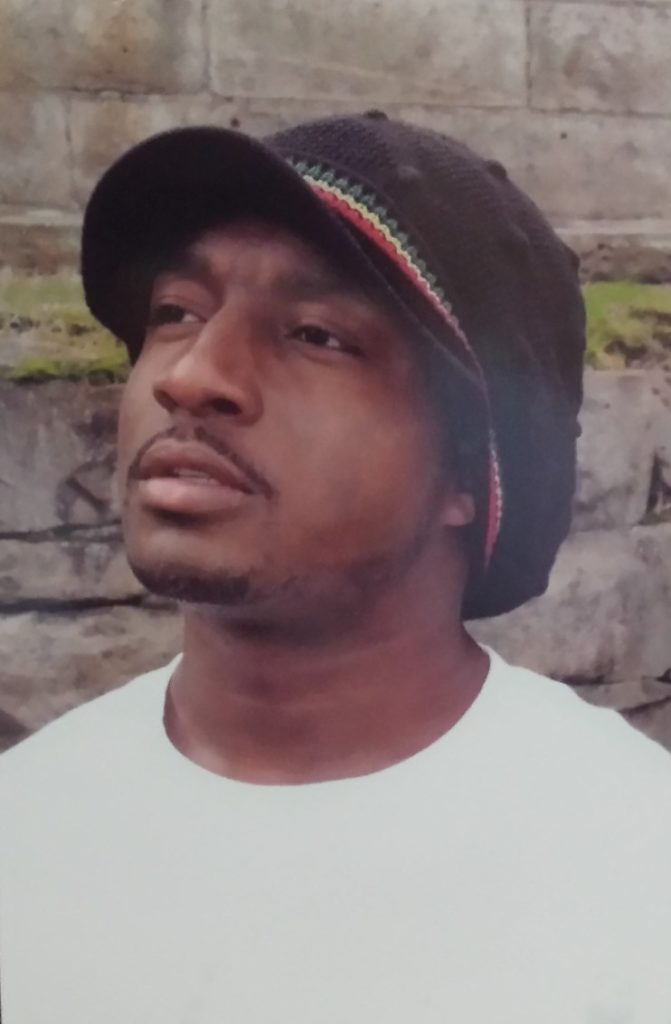

We bonded over Newport cigarettes, shared adversity and the recent events that brought us to Death Row. As the menthol smoke spewed from our lungs and dissipated into nothingness, so too did the intensity ease from Eric’s face. What I once thought was an unruly, trouble-making thug was really a harmless-looking average guy. Harmless with the potential to be lethal, like a steel trap that lies rusting idly away over time as long as nobody comes fucking with it. His brown eyes gleamed with the curiosity of someone eager to learn. His skin was the color of sunset at the end of a blistering day. A man in his early twenties, his youthful facial features were likely to require proof of I.D., with a gap-tooth smile that he sported with such confidence it left him on the right side of handsome.

He said he preferred to be called E-Boogie. Funny. He didn’t seem like the dancing type. He bobbed when he walked, his arm like a pendulum swaying ridiculously side-to-side with each step, but that appeared to be the extent of his rhythm. Still, it occurred to me that almost every black person on Death Row went by a nickname. Bedrock. Yard Dog. Napalm. Dreadz. There was even an Insane. I thought to get me one since the name ‘Terry’ was in no way as intimidating as Insane. That was the night I became known as Eye-G and E-Boogie and I first shook hands.

In the days and weeks to come, E-Boogie and I grew to know more about each other. I considered my own story as boring as a silent film, but his was action-packed. He told me about being a military brat, though I must say it sounded more like a confession. The packing up and leaving friends, always the new guy at school, the unstableness of it all. I couldn’t pretend to know the struggles of life on the base, so I mostly listened. Many of his tales lasted about as long as a punch line, then he was on to the next. It was only when he reached his experiences with gangs that he spoke at length. The only thing I knew about gangs was that I didn’t want to know about gangs but without it I could never fully come to know and understand E-Boogie.

Out of tolerating our differences, we found we had many things in common. We played basketball together every day, usually on the same team, but we both had a competitive spirit so rivalry was in the air. Our love for music kept us up at night listening to rap songs and debating which hiphop artist was better. Sometimes it was an all day affair at the poker table, cheating our asses off with hand signals only to walk away with a few pennies to show. We liked the same movies, ate the same foods and drank about the same amount of prison hooch before staggering to our bunks and crashing for the night. Every day spent with Eric was taxing yet we woke up and did it all over again as our shenanigans kept the adverse conditions of Death Row at bay and staved off the awaiting pain.

Our coping with conviction did not come without dissent from the other inmates. Some thought that our rowdiness violated their personal space. It kind of did, but it wasn’t intentional. Prison strips a person of almost every dignity, every liberty you could think of until all you have is an incredible sense of personal space. It’s all bullshit when even our personal space belongs to the state, yet it’s the only thing left for us to claim in this world in order to say we’re still here. No one understood that more than me. Hell, I was holding on to something too. While they were griping about personal space, I was fighting to keep my sanity. Even E-Boogie and all his thug moodiness would not deliberately infringe on someone’s personal space. Yeah… he was mad as hell at times, but I think it was more at himself. His and my antics were simply that – antics to distract from the chaos of having a death sentence. It was hard to accept the reality that my life as I knew it was over.

Nothing good lasts forever. That’s the motto of Death Row. We’d gone a few months fending off the misery and picking each other’s spirits up. Maybe we had no right to be enjoying ourselves while Death Row was grinding away at the minds of those around us. Well, E-Boogie and I would both learn that the misery was infallible and friendships were bound to suffer. It started one day with a dispute between he and I over something so petty I can’t remember. The exchange got heated. We both were talking shit. Suddenly E-Boogie called me out to fight. We argued over something so frivolous I believed he wasn’t serious. I walked up to him, looked him in the eyes – and he punched me in the face. I was so shocked, my breath caught in my chest and my heart sunk with betrayal. Eric, the person I relied on the most, had violated my personal space. The fight that ensued wasn’t much of a fight at all, rather a bunch of grappling to try and salvage our friendship. Before the day was over, we were back in each other’s good graces… but something between us had changed.

Afterwards we explored other friendships while maintaining a strained connection. We still got together and did all the things we enjoyed, but when it was over we’d go our separate ways. Eric made friends with a few people whose company I did not care for. Even from a distance, I could see his mood darkening to a point where I was overly concerned. He started getting into fights, in fact, he and I would go another round. It wasn’t anything our friendship couldn’t survive, but it wedged us further apart. One day we watched Eric’s sister, Kanetra, play college basketball before the nation on TV. After the game he went to his cell and closed the door, proud and isolated for two days.

On a few occasions he and I got together and talked like old times. I hadn’t realized how much I missed him. At the time, I wasn’t doing all that great in coping with Death Row, but Eric seemed to be doing a lot worse. I promised myself I would be there for him more, the way he was there for me.

Eric opted out of the annual basketball tournament, which left everybody on Death Row like… “What?” He was a top player. He upped everybody’s game. The tournament wouldn’t be the same without him. He did, however, coach that year. I was chosen to play on his team and man – we butted heads all season. I didn’t expect favoritism, I was too proud for that. I earned my spot on the team. In the end, we lost terribly in the elimination round, and I didn’t speak to Eric for over a week. Now, I wish I had.

I was at the card table that day when the announcement came over the PA system.

“Lockdown. Lockdown. All inmates report to your assigned cell. Lockdown. Report to your cells now.”

It was 5:00 p.m. We hadn’t gone to dinner yet. What the hell was going on? We packed up the poker chips and headed to our rooms. My biggest concern was winning my money back. The chatter started behind the doors. Speculation mostly. A fight broke out downstairs. A fight? Downstairs? E-Boogie was housed downstairs. Money was now the furthest thing from my mind. I knew in my heart it was Eric. The cell doors stayed closed throughout the night, and I went to bed wondering with whom Eric had a fight.

The next morning, I was standing in front of the mirror brushing my teeth when a guy popped up at the door. His face was rather long, his eyes dodgy, and he shifted from one heel to the other. He said that he was just dropping by to check on me since he knew E-Boogie and I were close.

“What the hell you talkin’ ‘bout? What happened to E-Boogie?” I asked.

“He hung himself, dawg. E-Boogie is dead.”

There were no tears to soothe the burning in my eyes as they were a river cascading down my heart. I wanted to sling my toothbrush aside, run downstairs and save him, but my chance for that was gone. I couldn’t remember the last words I said to him, and I couldn’t forget saying nothing. I felt like I failed him for not being there for him like he was for me when I needed a friend the most. The word about Eric spread like wild fire in a gasoline storm. He was found hanging in a mop room closet and pronounced dead on the scene. I realized Eric had been fighting after all; I just never guessed it was a fight with himself. Maybe there wasn’t much I could have done about that, but I owed it to him to try.

Eric Queen perished on August 5, 2007. He was 28. He was a hothead at times, but he was generous and if he loved you, he made sure you knew it. Eric made mistakes in his life, but I never heard him make excuses. In fact, one time he said to me, “Life don’t bend over for nobody, Eye-G. We just gotta roll with it.”

I’m still wondering where he got that from with his young ass. Eric swore he was a philosopher, and at times he really was. Dude was smart as hell. He could figure out anything – he just chose to figure out the streets. Can’t say I blame ‘im. The streets are tempting; they’ve led a lot of good people down bad paths. Still, there is redeem-ability after the streets. I wonder if Eric believed he could be redeemed. We never talked particularly about the crime that led him to Death Row, so no speculation there. But I know he had regrets in other areas of his life – we both did. It was us sharing those stories and being vulnerable with one another where we became like brothers. I just wish he knew his life was so much more than the evil that plagued him that day. If nothing else, his redeeming quality was in all that he did for me. I was spiraling into an unhealthy mental space when he walked through the doors that night. Eric put aside his own burdens to get me through my worst of times. I only wish I could’ve done the same for him… maybe through my writings I can still try.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Terry Robinson writes under the pen name ‘Chanton’, is a member of the Board of Directors of WITS, and heads up a book club on NC’s Death Row. When he first started writing for WITS, it was apparent he was a gifted writer, but he keeps striving for more – and he continues to achieve it.

Terry continues to work on his memoirs, as well as a book of fiction, and he can be contacted at:

Terry Robinson #0349019

Central Prison

P.O. Box 247

Phoenix, MD 21131

He can also be contacted via textbehind.com

![]()