It was December 5th, 1998, when I stepped outside of Jimmy’s nightclub at 2 a.m. The strip was packed with inebriated club hoppers loitering on the sidewalks. Cars blared their stereo systems, and the scent of ganja lingered in the night air. With 15 grams of cocaine stashed in my jacket, I decided to head home. I had no intention of being around when the cops showed. I popped on my headset and bopped to the lyrical testimonies of Tupac Shakur, “Come listen to my truest thoughts, my truest feelings, all my peers doin’ years behind drug dealing…”

It was December 5th, 1998, when I stepped outside of Jimmy’s nightclub at 2 a.m. The strip was packed with inebriated club hoppers loitering on the sidewalks. Cars blared their stereo systems, and the scent of ganja lingered in the night air. With 15 grams of cocaine stashed in my jacket, I decided to head home. I had no intention of being around when the cops showed. I popped on my headset and bopped to the lyrical testimonies of Tupac Shakur, “Come listen to my truest thoughts, my truest feelings, all my peers doin’ years behind drug dealing…”

Scanning the crowd, I readied for my departure when I spotted a familiar face. “Oh shit! That’s Crip.”

His lean, wiry frame was indistinguishable under baggy clothing with dangling dreadlocks that curtained his face, but I was convinced – the nerve of the guy to show his face. He and I should not be in the same club scene, not after last week. Confrontation was inevitable. My only advantage was that I saw him first.

I slunk behind a group of people, then hurried across the street. Advancing alongside the building where Crip stood, I drew the 9mm handgun from my waist and chambered a live round. Intended as a last resort, I shoved the heavy steel into my back pocket, and rounded the corner. There was Crip…

Our eyes locked in a silent exchange that revealed an awful truth – we were both bound by circumstances, and there was no turning back. I lowered my gaze and eased onward, careful not to alarm him. At precisely the moment we stood at arm’s length, I spun, fists clenched, and demanded, “What’s up mutha fucka? Which one of ya’ll niggas shot at me?”

His eyes widened with the shock of being accosted as he raised his shirt and pulled a .357 revolver. I figured if I went for my own gun now, we would likely kill each other. Instead, I flashed my palms, stepped back, and hoped to dissuade him with an explanation. “What the fuck man? I was just…”

That’s as far as I got before my words were cut short by the sudden jerk of his hand. I turned and dashed for cover, yet there wasn’t any place to hide. Crip thrust the chrome tool at my chest and fired. POW!

The deafening sound sent shock waves through my body as I stood frozen with fear. My impulse trumped all ability to reason, and I pulled out the 9mm. The Crip I saw now was different, as though he’d undergone a fiendish transformation. His lips were curled in a fierce snarl, and there was confidence in his eyes that pierced. Again his hand snaked forward in a lethal jab. I pointed my gun, desperate to stop him.

Joint blasts amplified the terror between us and sent bystanders scurrying to safety. My legs tore away with a mind of their own as another pop sounded behind me. I squeezed the trigger, but nothing happened. Two strides later, I crashed to the ground, the brutal impact smashing my watchcase and wrenching the 9mm free. My legs felt locked in a whirlwind, yet when I checked them, they were still.

Damn. I was shot.

I struggled to rise, but slipped back down to the crunch of scattered debris. The 9mm laid inches from my face with a spent shell casing lodged in the chamber. I reached for it but faltered, thwarted by sudden paralysis. Then the unexplainable happened. I began to relive my entire life through a surge of memories and emotions. The sensation catapulted me through a space in time, nearly causing me to forget about Crip.

A swift search revealed that I’d fallen around the corner. I didn’t know if Crip was even injured. I expected him to step around the corner and kill me at any moment. Empowered by the urgency to prevent my death, I grasped the gun. With a violent shake, the casing sprang loose and tinged against the asphalt. I rolled and popped off a series of shots in the sky and waited for Crip to show.

As dozens of footsteps converged towards me, I was imbued with panic. I trained the gun on the first face that hovered, only to see it was a friend who’d rushed to help. At his request, I ceded the gun and watched as he bolted around the corner. More faces appeared, suspended above me, annoying me with their questions and concerns. My backside raged with pain as if being cauterized with a searing stake, while pressure penned my chest, causing my breathing to strain. With each new face that happened into view, a fraction of the air was claimed, as my vision succumbed to a fierce swirl that distorted the surroundings. Voices were reduced to murmurs over the thumping of my chest.

As dozens of footsteps converged towards me, I was imbued with panic. I trained the gun on the first face that hovered, only to see it was a friend who’d rushed to help. At his request, I ceded the gun and watched as he bolted around the corner. More faces appeared, suspended above me, annoying me with their questions and concerns. My backside raged with pain as if being cauterized with a searing stake, while pressure penned my chest, causing my breathing to strain. With each new face that happened into view, a fraction of the air was claimed, as my vision succumbed to a fierce swirl that distorted the surroundings. Voices were reduced to murmurs over the thumping of my chest.

“I… can’t… breathe…” I whispered, my voice scraggly and feeble. “Move them back, man, I can’t breathe.”

Pandemonium swelled as onlookers gathered and cast down stares of sympathy. Then a voice emerged, booming in the distance, “Ya’ll git the fuck back!”

Although I was unable to see his face, his commanding ways consoled me. “Stop panicking, Duck…,” I heard him say, “…if not, you’re gonna die.”

I closed my eyes, stilled myself, and relinquished my woeful struggles. I drew on a spiritual medium where inner calmness was fostered. Compelled by the notion to atone, I immersed myself in prayer, neither for forgiveness nor some half-hearted attempt to explain away my misdeeds, but a prayer of strength for my mother. I wanted her to know how much I loved her and thought she deserved better. Afterward, I wasn’t afraid anymore. I was ready for the final transition.

I closed my eyes, stilled myself, and relinquished my woeful struggles. I drew on a spiritual medium where inner calmness was fostered. Compelled by the notion to atone, I immersed myself in prayer, neither for forgiveness nor some half-hearted attempt to explain away my misdeeds, but a prayer of strength for my mother. I wanted her to know how much I loved her and thought she deserved better. Afterward, I wasn’t afraid anymore. I was ready for the final transition.

As I journeyed toward that terrible darkness to end my worldly suffering, I held on to the vision of my mother and let go of everything else…

©Chanton

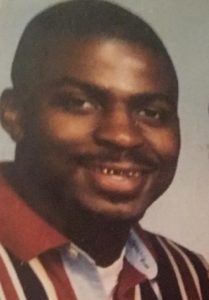

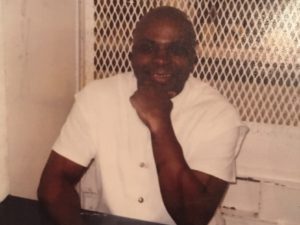

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Chanton is a thoughtful and gifted writer as well as a frequent contributor.

![]()

‘Have you ever felt like you can taste the future? Like you know what’s about to happen? That’s how I feel. Back a few years ago, a friend here broke away from the officers who were escorting him and walked towards me in the dayroom. On instinct, I reached out through the bars and grabbed him. Tears stained his face from crying for hours during his last visit. I gave him a huge hug, and he kissed my cheek and whispered in my ear, “Roaddawg. You have the best chance to get free. Don’t let them win. Go back home to your family. Get free. Promise me?”’

‘Have you ever felt like you can taste the future? Like you know what’s about to happen? That’s how I feel. Back a few years ago, a friend here broke away from the officers who were escorting him and walked towards me in the dayroom. On instinct, I reached out through the bars and grabbed him. Tears stained his face from crying for hours during his last visit. I gave him a huge hug, and he kissed my cheek and whispered in my ear, “Roaddawg. You have the best chance to get free. Don’t let them win. Go back home to your family. Get free. Promise me?”’  If these bars could talk,

If these bars could talk, I’ve spent almost half my life here. During that time, I’ve done everything possible to return home – to leave this place and return to society. I’ve abandoned fear, anger, bad feelings, all in search of the way – my own walk.

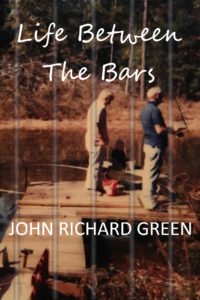

I’ve spent almost half my life here. During that time, I’ve done everything possible to return home – to leave this place and return to society. I’ve abandoned fear, anger, bad feelings, all in search of the way – my own walk. ABOUT THE AUTHOR. Shipwrecked and found. John is currently doing a two-year set off, after 25 years of incarceration. He is a frequent contributor as well as the author of

ABOUT THE AUTHOR. Shipwrecked and found. John is currently doing a two-year set off, after 25 years of incarceration. He is a frequent contributor as well as the author of

Back in the hallway we continue until we reach the end. There is a door in front of us that leads to the electric chair and a door to the left that leads to the death row housing unit. The Sergeant taps it with his keys, and a guard who looks like he should be just entering high school opens the door.

Back in the hallway we continue until we reach the end. There is a door in front of us that leads to the electric chair and a door to the left that leads to the death row housing unit. The Sergeant taps it with his keys, and a guard who looks like he should be just entering high school opens the door. After they leave, I look around for a light and spot a string in the corner dangling from the ceiling. I pull it, and a dim, 40-watt bulb comes to life. Roaches scurry everywhere.

After they leave, I look around for a light and spot a string in the corner dangling from the ceiling. I pull it, and a dim, 40-watt bulb comes to life. Roaches scurry everywhere. I had just kicked back for the night and began to relax – boots off, feet up – when I sensed movement off to my right. It was him – my boy was nearly four years old and had long blonde hair. He was motionless, staring, and I finally asked, “What is it?”

I had just kicked back for the night and began to relax – boots off, feet up – when I sensed movement off to my right. It was him – my boy was nearly four years old and had long blonde hair. He was motionless, staring, and I finally asked, “What is it?” “See?” I rifled through the garments checking the corners. “There’s no monster in here.” I knelt down to his eye level, “and there won’t ever be, because they know I will get after them if they ever get close to you. Okay?”

“See?” I rifled through the garments checking the corners. “There’s no monster in here.” I knelt down to his eye level, “and there won’t ever be, because they know I will get after them if they ever get close to you. Okay?”