“What does it feel like to be innocent on Death Row?”

My answer?

“A setback for mankind.”

I was born in the ‘70s to black parents in black times in a world that was gray at best. My earliest lessons on guilt were not determined by wrongdoings, but by the color of one’s skin. I saw the guilty as they were dipped in tar and strung up for public viewing, or set upon for sitting down to eat. Guilt then becomes a psychological impression on the minds of black communities; a sense of guilt that is the origin of the criminal mind – a reflection of how we feel. Guilt is the cultural identity that leaves behind a trail of regrets, so I am dissociated with feeling innocent in a country that charges people guilty for having black skin.

I was convicted of the murder of a restaurant manager in April, 2000, and sentenced to die by a consenting jury by way of lethal injection. Arriving on Death Row, I conceded two things – my innocence was insignificant and justice grotesquely one-sided. I decided that neither guilt nor innocence had brought me there – it was powerlessness. I was powerless to take charge of my life and break the cycle of recidivism. I was put on the path to prison at the age of seven, the time I first stole, my impropriety promising to progress over time. By the age of twenty-seven, I was the product of circumstances and my road ended here, yet despite all my wrongdoings, still I did not deserve to be on Death Row.

I avoided eye contact with men, sparse with my words, afraid that my difference would show and the rapists, brutes and murderers would figure out I was not. There was no introduction guide to Death Row, but if there was, I imagined it would’ve read,

Innocence does not thrive here,

your hope is your despair.

For the first year, I uttered not a word about innocence, though the subject was one of recurrence, casually hinted at by some in conversations, while others were more straightforward. I wondered if my own innocence sounded as disingenuous as theirs when spoken aloud. The improbability of their innocence caused me to dismiss their claims as prison colloquialism.

Over time, I learned to shelve my innocence while emulating the hardened killers. I was wary and distrusting, argumentative, and constantly on the lookout for a fight. At night, sometimes, my mind broke free, much to my dismay. I never knew fantasizing could hurt so bad. I envisioned life as a working-class citizen, doing stringent work that was wearisome but decent, with a pension as opposed to a penalty. Other times, I grasped at the wilting memories of family and friends as their influence crumbled under their hefty absence, and their faces yielded to time.

Then came the biggest news… a Death Row man was freed from here after being awarded a new trial. I was skeptical, challenged his innocence, as he was someone I previously dismissed. Still the question lingered… what if he was innocent? And what if there were others? These men I’d subjected to my silent criticism, fostered by widespread belief. Unable to relate due to their menacing aura, my innocence was too fragile to trust, so I rejected them based solely on my preconceived notion. It was the very same rejection I feared. I wanted to be happy for a guy whose stay on Death Row was at its end, but with my errant dismissal of him and my own self interest, I was too ashamed.

As the years rolled by, cases were amended and death sentences overturned – mental retardation and the prohibiting of minors were enactments that saved lives. In some few cases, the men were exonerated on the likelihood of innocence, an unsettling error revealing that behind the virtue of our courts was depravity. There was a time when I presumed our judicial system stood on the right side of public service, but with the growing number of death sentences vacated, an alarming truth emerged. Wrongful convictions were not the result of legal mishaps – but a setback in the evolution of justice. It was a systemic trade-off, conviction rates in return for support at the ballots. On the verge of understanding how my injustice came to be, I was nowhere close to help, as I struggled to wish well those men who departed… their hope was my despair.

Every day I longed for my freedom until all my hope was spent, and I was left with nothing more than a stale existence. With each reversal, I felt sorely abandoned by the securities of the laws. I pondered the plausibility of my injustice and came away rejecting myself. I used recreational drugs, obscenities and conflict to propel my downward spiral. I severed outside connections, quit my aspirations and rigorously questioned my faith. It seemed my road didn’t stop on Death Row, but I was headed to a place much darker, and no matter how far my mind drifted from my mad reality, the executions pulled me back.

On those nights I ached helplessly as the clock wound down on the lives of men tethered to a gurney. I wondered if they winced at the needle’s prick like I did as a kid at the clinic, or closed their eyes in defiance to die alone. Done with feeling helpless, I put their deaths out of my mind and tried to remain unaffected by the executions until a death date arrived for a friend of mine… and my helplessness turned to surrender.

It was thirteen years later before I gained some clarity into the disorder taking place in my life. It began with written essays that chronicled my past offenses, offenses unrelated to my stay here, restoring in me a sense of worth. Accountability for my previous wrongs – saved my life. Without it, I would’ve given up. With the many death sentences being vacated, I couldn’t wait one more turn, and through accountability, I discovered there was redemption behind these walls, the potential to reinvent the principles of humanity – and the most promising yet was the willingness of these men to die with more dignity than that with which they lived.

So, what is it like to be innocent on Death Row is best answered by the word ‘unrest’. It is a constant grinding of the mind in an effort to determine how we tolerate such criminal indecency. My being wrongfully convicted is a laborious affliction under the stigmatic strain of disbelief – a strain that offered one resolve for me, complacency for my accusers. It’s lonely being innocent with no one to talk to about the certainty of my innocence. And frightening. Only Ichabod Crane, a character from my childhood, terrified me so. Often enough, being innocent feels pointless after 21 years of punishment, when death is no longer a menacing possibility but a welcome alternative.

Being innocent on Death Row is soulfully depressing, granting little peace of mind. It is my fight to hold on to the hope I deserve, when the culpability isn’t mine to bear. My innocence is no more relevant than the next man’s guilt when the ink on our status reads the same – and yet, what does it matter, guilt or innocence, in a nation such as our own, where both are punishable by death.

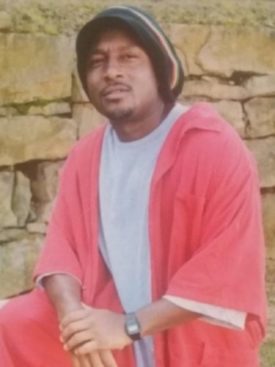

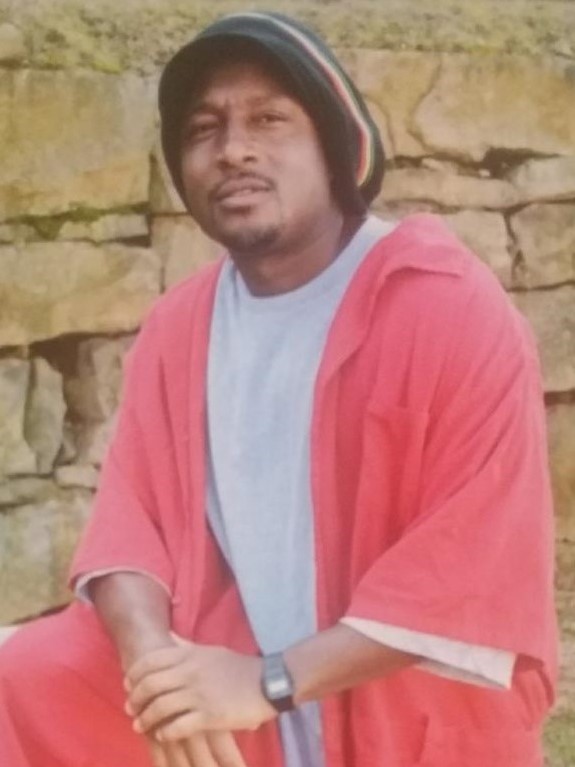

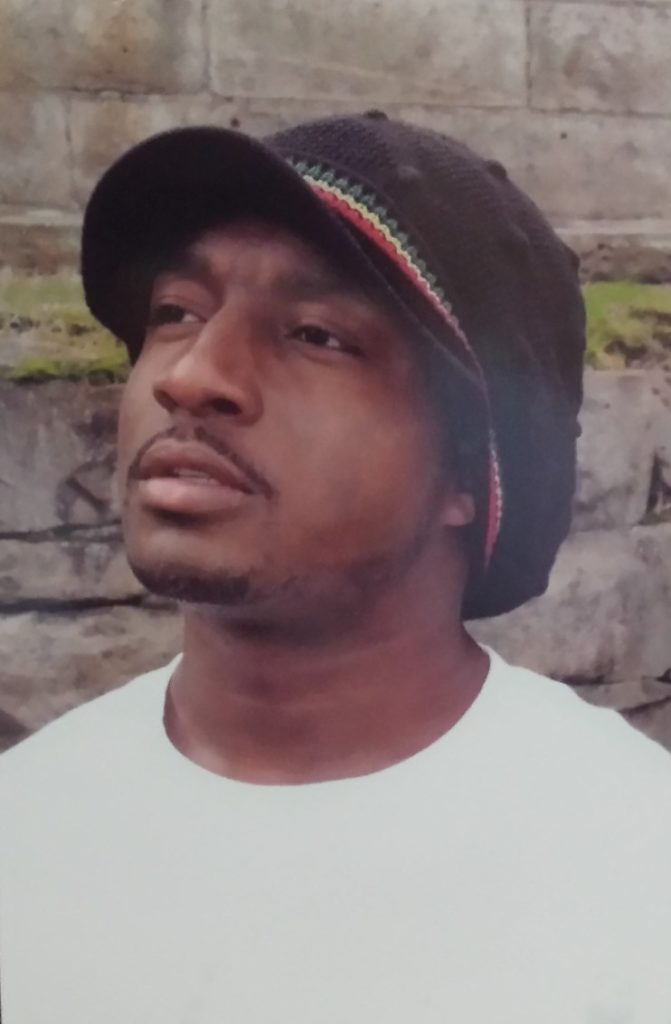

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: ‘Chanton’, is a member of the Board of Directors of WITS, and heads up a book club on NC’s Death Row.

He has always maintained his innocence, and WITS will continue to share his story and his case. On our Facebook page, we regularly share stories of wrongful convictions, they are real, frequent, and Terry has been living one for over two decades.

Terry continues to work on his memoirs, as well as a book of fiction, and he can be contacted at (Please Note, this is a change of address, as NC has revised the way those in prison receive mail):

Terry Robinson #0349019

Central Prison

P.O. Box 247

Phoenix, MD 21131

OR

textbehind.com

![]()