Having served over 38 years, guilty or innocent, I wake each morning to the profound reality of doing life in prison. This is not what I or any man was created for. But here I am in a box, caged like an animal, and as the tours come through, I’m often looked upon as such.

Yes, a man, a human no less, but looked at and treated as other than, the wretch of the earth.

I have a friend who wrote a book titled, ‘A Costly American Hatred’. His name is Joseph Dole. In the foreword he states, “At one time lepers were segregated from society and exiled for life to leper colonies.” A new type of leper and leper colony has taken their place in America. People who commit crimes are the new leper. The new leper colonies are prisons, sprung up across our nation like Starbucks.

Doing life is not easy, and one has to adjust and continue to adjust as the hours, days, months and years go by. And as life – your life, my life – plays out, one has to remain hopeful. I first entered prison without a care. I still had a woman and family. In a span of a few years, they were gone. The losses unimaginable. I spoke to my mother on the phone weekly and got an occasional visit, but life as I knew it changed the moment the judge found me guilty.

When you enter the belly of the beast, trust me, your life will change too. That’s a fact. I had no heart when I first arrived. I was as cold as the steel that confined me. I often applauded the misfortune of others that played out on the news and before my eyes. Sometimes, I played a part in the demise. I was a young son with an estranged woman, who became hooked on drugs. I had a mother trying to be the conduit of help and a good grandmother while also a parent to me. I was doing time, gang-banging, getting high and doing much of what I had been doing on the street. I was numb to the time I had to do. I had yet to realize I was doing the best I could to escape reality.

Each year time gets harder as the prison industry dries up. The prisoncrats took back their prisons and commerce has dried up as well. As an artist, the end of arts and craft shows and being allowed to sell our art to officers and visitors was a game changer. I went from earning a few hundred dollars each month to depending on a state stipend of $10.00. Trust me, that doesn’t go a long way in prison these days.

Now I sit here with no family, my mother gone, and a brother who hasn’t spoken to me or my son in over twenty years. There is no other family. I had a woman for over twenty of the thirty plus years. She was a rock in and out of my life. She would help me weather many a storm, but at seventy plus years of age and chronic everything, time has crippled her in many, many ways. Years have gone by, and I haven’t heard a word from her. Time waits for no one.

I too have aged. I’m blessed to have my son here with me in prison, but it’s certainly not where I want him to be. As an elder, our relationship affords me a bit of comfort many my age do not have here. Life has taken a toll on my body, but not my spirit. I hold on to hope and dream of being free! But I also face the awesome reality that I may die in here. That’s real and something I think about often. I ask myself, what will my legacy be?

Up until the point when I changed my life, I was en route to further failure and the banner of having been born and died and absolutely nothing else. It’s my hope, my fervent prayer, that my legacy will be that of a man who helped shape the futures of young men who came through this penal institution, especially those now in the free world. I hope that I have helped them change their lives for the better, and that I have given some hope, some insight into making better decisions.

As for my son, I am honored to have shown him the other man, not the gang-banging, ice-cold, uncaring man who caused harm and damage to men, women and community, but a visible man of Yah (God). A man who shows and teaches the lessons of love, respect and compassion. A man who shows how important it is to extend our hands to our elders. A man who has always extended his hand to the many sons I’ve adopted during my journey in prison.

I want my legacy to be that I was a man of Yah, who with each new breath of life represented the banner of my holy name – Ananyah – which means, he has covered or the covering of Yah (God). I would like my legacy to be that my writings I once did for the youth on life from lock down, provided a teachable moment, a vision, and led readers to see, know and hear the truth of my words.

I want you to think of your favorite part of the day, when everything else stops. Taking your children to the park, the warm embrace of a loved one, waking to the one you love, or just a simple cone of ice cream. Your favorite home-cooked meal or a nice refreshing shower. Now, imagine that moment gone forever – that’s doing life in prison, my friend.

A sentence of life without the possibility of parole, is a death sentence, but worse. It’s a long, slow, dissipating death without any of the legal or administrative safeguards rightly awarded to those condemned to the traditional form of execution. Life in prison is indeed the other death penalty. It exposes our society’s concealed belief that redemption and personal transformation are not possible, thus no one is vested in us except for the monetary value our incarceration provides.

You have the ability to chart a new course has always been my belief and message. I’ve expressed concern to the youth and parents of youth in hope they avoid sitting in one of the many cells available in the US Penal System – like I am.

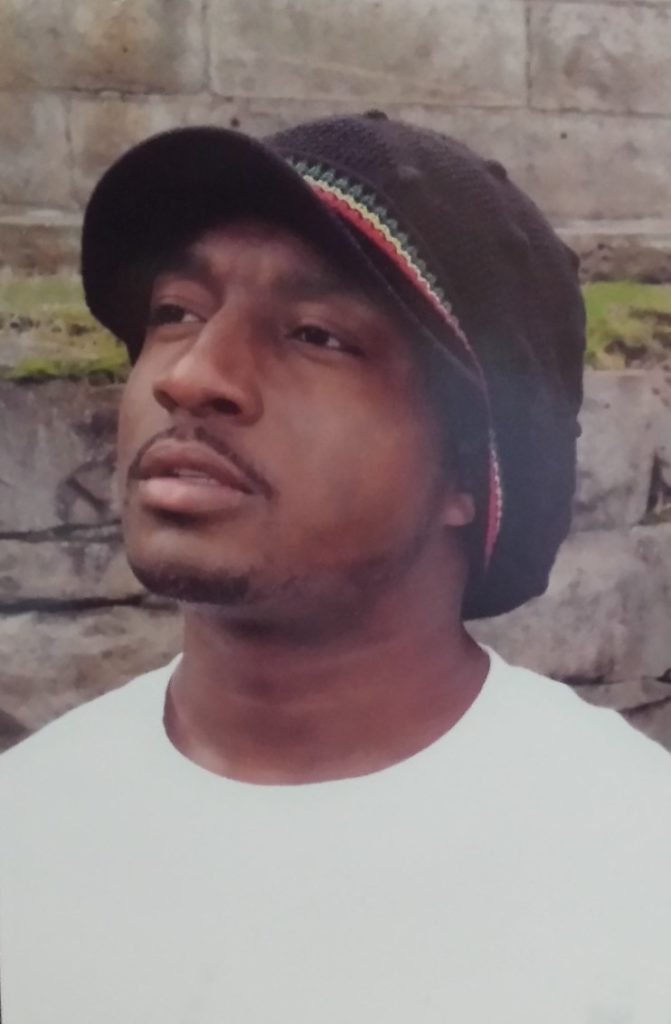

ABOUT THE AUTHOR. Kenneth Key is an accomplished artist and writer and can be contacted at:

Kenneth Key #A70562

P.O. Box 112

Joliet, Illinois 60434-0112

![]()