Suicides, assaults, perpetuated acts of nonsense, exonerations, relationships severed and put back together – I thought I’d experienced all there was on Death Row. I’ve seen mild, treatable medical conditions fester and decline, often turning fatal due to inadequate healthcare. And I’ve seen the dismal look in a man’s eyes, helpless and void, moments away from being executed – yet even after twenty years, nothing could’ve prepared me for today.

For over six months now, due to global restrictions imposed to prevent the spread of COVID-19, all weekly in-person Death Row visitation has been suspended. As an alternative, online video visitation was implemented, which was a welcome remedy to the growing concerns of our loved ones for our well-being. For men decades removed from society, video visits ignited Death Row with an ever burning anticipation to view our family in the comforts of their homes as opposed to a concrete booth with reinforced glass and steel bars. Appointments were made faster than a sweepstakes giveaway and everyone that returned from a visit had a tale to tell, some recounted with exuberant smiles, some with heavy hearts.

In the following weeks, as per safety regulations, the site for Death Row video visits was moved to another area in the prison. Many of us know the new location as the ‘Death Watch’. It’s where capital punishment is performed. Few men here have suffered the Death Watch prior to having their scheduled executions vacated, one in particular describing the most dreadful night ever with a broken voice to match. More often, the men who’d been hauled off to the Death Watch would not return. It was a wasteland that was now being assigned familial merit and a path on which I would walk.

Friday, September 18, 2020, at 9:03 a.m., a call blared over the P/A system, one that came expectedly as I had awaited the sound since the night before. It would be my first video visit with my family, whom I hadn’t seen in months. The anticipation of it all elevated my mood beyond the reach of my daily struggles. I hopped into the standard Death Row uniform, one meant to evoke guilt – a hot red jumper that draws heavy around the shoulders in a color scheme that clashes with one’s dignity. With nothing left to do but settle my eagerness, I strapped on my face mask and headed on my way.

I joined the company of two other inmates, also with scheduled visits, as they shuffled slightly on their heels, anxious to be off. One guy, like myself, was a first-timer; I surmised he was equally as nervous. The other inmate had attended video visits prior and schooled me on what was to come.

With the arrival of the escorting officer, we set out on our trip from the Death Row facility down to an area usually reserved for visitation, nothing to heighten the excitement along the way, yet nothing to diminish it. We then discontinued the familiar route and veered down a flight of stairs, a control station identical to the one above at the bottom. We crossed the lobby to a sliding glass door that held beyond its threshold something menacing – the very path condemned men had journeyed before as they faced a despicable end.

The door cranked open with a woeful whine, like a symphony of restless souls. I followed the group as they seemingly proceeded with no ills for our whereabouts. What looked to be a short distance to the other end of the hallway became a faraway stretch of land, my steps laden with the realization that, for some, this was their final walk.

Rows of windows, made murky and distorted to deny one last peaceful look at nature, lined the passageway. Here, nothing would be offered to soothe the spirit of the wretched, though in a failed act of humanity, sedatives would be used to ease their pain. At the midway point was a sally port with its inner workings obscured as it sprang into view like a childhood boogeyman, chasing away my sense of security. I needn’t inquire of anyone to know this was the Death Watch. It appeared nothing like the horror I’d dreamed of, yet it incited the same despair. I was standing in the final resting place of a friend of mine named Joe who was executed in ’03 by lethal injection. Longing for his company, I whispered to myself and hoped he could hear me.

We made our way to a waiting area, each taking up a station as the first of us was ushered away to begin his scheduled visit. It would be some twenty minutes later before he returned, talkative and rather giddy as the next guy hurried off in his place. I sat and thought of all the laws passed over the years that would’ve prevented some executions, like the Mental Retardation bill that would’ve saved a man named Perry, or the Racial Justice act for another guy, Insane. One law that was enacted excluded defendants under eighteen years of age from being eligible to receive the death penalty, an amendment that would’ve kept two other men, Hassan and J-Rock, alive today.

The second inmate emerged with a smile so bright I soaked up a bit of his joy. I was sure that I’d seen the worst of the Death Watch. I couldn’t have been more wrong.

I stepped around the corner to what I thought would be a cozy, makeshift cubicle with a monitor on which the faces of my loved ones awaited. Instead, I happened onto an arching hallway with blinding lights at the far-end and a metal tank made obvious by the gear-wheel bolted to the door. I was told it was the crank that released the gasses into the chamber during executions. Beside the Death Tank was the viewing area, where the deaths have actually been watched by those who would champion vengeance while holding others to a different standard. I cringed at the thought of such an immoral practice and the historical transgressions. I’ve often wondered if my friends felt alone when they were executed – part of me now prays that they did.

After visitation, I passed by the infamous Death Chamber once more and peered into the darkened sarcophagus. I had hoped to get a feel for my friend, Joe, but all I got was a question of fate.

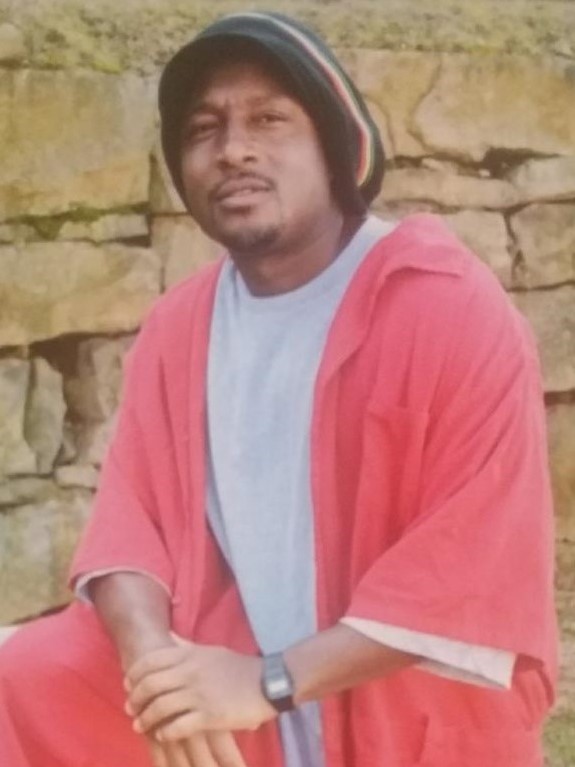

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Terry Robinson often writes under the pen name ‘Chanton’, and this year he and others co-authored Crimson Letters, Voices From Death Row. He continues to work on his memoirs, as well as a book of fiction. Terry Robinson has always maintained his innocence, and hopes to one day prove that and walk free. Mr. Robinson can be contacted at:

Terry Robinson #0349019

Central Prison

4285 Mail Service Center

Raleigh, NC 27699-4285

![]()