In 1999, the year Charles Mamou was sentenced to death, Texas performed 35 executions. The following year, they performed 40. The state was and is very practiced at executions – but has it become too easy to execute?

In 1999, the year Charles Mamou was sentenced to death, Texas performed 35 executions. The following year, they performed 40. The state was and is very practiced at executions – but has it become too easy to execute?

Tough on crime is one thing, execution quite another. There is no do-over. The system is not faultless. Innocent people have been executed, and they will continue to be as long as there are executions. Those mistakes are more likely in a state that gets too comfortable executing. History has already proven that it sometimes doesn’t matter if the cases in question involve minorities or the poor or both.

As Charles Mamou’s execution inches closer, many who have looked closely at his case feel he won’t be executed because he is guilty of the crime for which he was sentenced. Some feel he will be executed because – Texas can.

Charles Mamou was guilty of being a drug dealer. But in the case of the murder he will die for – there were no eyewitnesses, no confessions, no DNA, and no physical evidence outside of a shell casing found near the body that cannot be definitively linked to anything – in spite of the prosecution’s arguments.

So, in a year in which Texas averaged about three executions a month, the testimony of a handful of drug dealers who had a lot to gain by pointing the finger away from themselves, sealed the fate of Charles Mamou. They didn’t even have to testify to witnessing the crime. They all had a lot to gain in a capital murder case with the death penalty on the table – and nothing to lose but their integrity.

The night of the drug deal that started it all, Kevin Walter, Dion Holley and Terrence Gibson had guns and planned to meet up with Charles Mamou and his friends to sell drugs – which actually were not drugs. They had nothing to sell. That is why they went to the meeting with guns. Each of the men intended to come away with cash from a drug sale in which they did not have drugs to sell. There is no doubt each of the three – Kevin Walter, Dion Holley and Terrence Gibson – intended to commit crimes that night with loaded guns in tow. They were willing to go to extreme lengths to commit their crimes. They also knew Mary Carmouche was out of sight and in their backseat. Mary would be found dead two days later.

The buyers were to be Terrence Dodson (not to be confused with Terrence Gibson), Samuel Johnson and Charles Mamou. Those three men also traveled with loaded guns and had no cash to make their purchase. It was a drug deal – a crime – in which all parties were planning to come out ahead, with little regard for the others involved. They weren’t there for charitable purposes – and the actions of them all indicated that at that point in time – they were each willing to give up their integrity for personal gain.

Of the sellers that night, Terrence Gibson lost his life. He had a loaded gun and no one was ever charged with his death, and if they had been, there would be a strong argument for self defense.

Dion Holley testified for the State at Charles Mamou’s trial, and it appears he was not charged with any crimes related to what happened that night. The vehicle the sellers were driving belonged to Dion Holley’s mother, and of the scant amount of evidence in this case, Dion’s print was the only one later found in the vehicle. And – it was Dion’s friend, Mary, who was hiding in the backseat of the car they arrived in. Holley testified regarding hearing shots at the drug deal, running, getting shot in the arm, seeing Mamou get in his mom’s car and hearing both cars leaving the scene of the drug deal.

Kevin Walter also testified for the State. It appears he was also not charged with any crimes related to what took place, although he testified regarding the plan he and his friends had to arrange a fake drug deal and rob Charles Mamou of $20,000. Mr. Walter was clear about his understanding of the planned robbery and his participation in it.

Samual Johnson testified for the State. It appears he was also not charged with any crimes related to what took place, although he testified regarding his own involvement in the plan to rob men of drugs and his connection to the crimes. Samual Johnson was the driver of the car that Charles Mamou arrived at the scene in. Charles Mamou was actually from Louisiana, and did not have a vehicle in Texas, nor was he as familiar with the area as the men he was working with.

Terrence Dodson testified for the State, although there was nothing he could testify to that would benefit the prosecution regarding what he had ‘seen’ that night, because he was not at the scene of the drug deal. But, according to court documents, Terrence Dodson was very involved in the drug deal, and it appears he was not charged with any related crimes. But, Terrence Dodson was instrumental in arranging the deal, and also intended to rob the dealers with a gun he had. Terrence Dodson had good reason to be concerned about what he might be charged with for his involvement in the murder, although he was not in the car by the time the deal actually took place. During the trial Dodson testified that Charles Mamou ‘confessed’ to him that he had committed the crime because the victim looked at him ‘funny’. Mamou has steadfastly denied this confession took place.

That is what the State had. That was the closest that they could get Charles Mamou to the actual murder through witness testimony – several young men who all had something to gain by working with the State, all involved in criminal activity, and all with questionable integrity going into the trial. Even with their testimony, which Mamou’s current defense says is ‘riddled with inconsistency’, none of them witnessed anything connected to a murder. Mamou has always maintained that after the drug deal gone wrong, he and Samual Johnson drove back to the apartment complex he was staying at. He was distraught and several other people saw Mary and interacted with her. That was the last night he ever saw her, and she was alive.

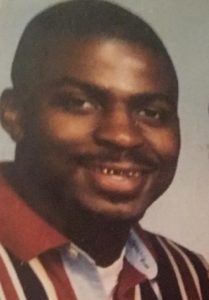

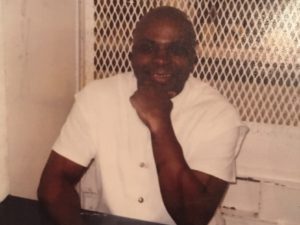

Some would say Charles Mamou doesn’t matter, because he was a drug dealer himself. It is correct that Charles Mamou was a drug dealer twenty years ago. Since that time he has spent all his days in a solitary cell on death row in the state of Texas. He’s now in his forties. The chance of him ever resuming a life of dealing drugs is near non-existent – and being a drug dealer is not a crime punishable with death in this country. If it were, the State’s key witnesses would be in neighboring cells.

Logic alone would make one question why Charles Mamou would call up a drug dealer and tell him he murdered someone because they looked at him ‘funny’, when he has steadfastly maintained his innocence.

One might also wonder how Charles Mamou located a deserted home in which to murder a girl in a state he didn’t even live in. The witnesses who testified against him would be more aware of the surrounding area and more capable of accomplishing that.

In the case of Charles Mamou an execution may allow Texas to close a chapter, but his death will not answer the question of who killed Mary Carmouche. There isn’t enough evidence to prove who killed her, and Texas quit looking for the answers soon after the crime took place.

REFERENCE

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS HOUSTON DIVISION. CHARLES MAMOU, JR., vs. WILLIAM STEPHENS, CASE No. 4:14-CV-00403, AMENDED PETITION FOR WRIT OF HABEAS CORPUS . 4 June 2015.

Related Articles: What Does It Take To Get On Texas Death Row;

Texas Death Sentence Clouded By Irrefutable Doubt;

Awaiting Execution – “Have You Ever Felt Like You Can Taste The Future?”;

Letter From Key Mamou Witness Contradicting Testimony;

Testimony Worthy Of An Execution? The Mamou Transcripts Part I

![]()

It was December 5th, 1998, when I stepped outside of Jimmy’s nightclub at 2 a.m. The strip was packed with inebriated club hoppers loitering on the sidewalks. Cars blared their stereo systems, and the scent of ganja lingered in the night air. With 15 grams of cocaine stashed in my jacket, I decided to head home. I had no intention of being around when the cops showed. I popped on my headset and bopped to the lyrical testimonies of Tupac Shakur, “Come listen to my truest thoughts, my truest feelings, all my peers doin’ years behind drug dealing…”

It was December 5th, 1998, when I stepped outside of Jimmy’s nightclub at 2 a.m. The strip was packed with inebriated club hoppers loitering on the sidewalks. Cars blared their stereo systems, and the scent of ganja lingered in the night air. With 15 grams of cocaine stashed in my jacket, I decided to head home. I had no intention of being around when the cops showed. I popped on my headset and bopped to the lyrical testimonies of Tupac Shakur, “Come listen to my truest thoughts, my truest feelings, all my peers doin’ years behind drug dealing…” As dozens of footsteps converged towards me, I was imbued with panic. I trained the gun on the first face that hovered, only to see it was a friend who’d rushed to help. At his request, I ceded the gun and watched as he bolted around the corner. More faces appeared, suspended above me, annoying me with their questions and concerns. My backside raged with pain as if being cauterized with a searing stake, while pressure penned my chest, causing my breathing to strain. With each new face that happened into view, a fraction of the air was claimed, as my vision succumbed to a fierce swirl that distorted the surroundings. Voices were reduced to murmurs over the thumping of my chest.

As dozens of footsteps converged towards me, I was imbued with panic. I trained the gun on the first face that hovered, only to see it was a friend who’d rushed to help. At his request, I ceded the gun and watched as he bolted around the corner. More faces appeared, suspended above me, annoying me with their questions and concerns. My backside raged with pain as if being cauterized with a searing stake, while pressure penned my chest, causing my breathing to strain. With each new face that happened into view, a fraction of the air was claimed, as my vision succumbed to a fierce swirl that distorted the surroundings. Voices were reduced to murmurs over the thumping of my chest. I closed my eyes, stilled myself, and relinquished my woeful struggles. I drew on a spiritual medium where inner calmness was fostered. Compelled by the notion to atone, I immersed myself in prayer, neither for forgiveness nor some half-hearted attempt to explain away my misdeeds, but a prayer of strength for my mother. I wanted her to know how much I loved her and thought she deserved better. Afterward, I wasn’t afraid anymore. I was ready for the final transition.

I closed my eyes, stilled myself, and relinquished my woeful struggles. I drew on a spiritual medium where inner calmness was fostered. Compelled by the notion to atone, I immersed myself in prayer, neither for forgiveness nor some half-hearted attempt to explain away my misdeeds, but a prayer of strength for my mother. I wanted her to know how much I loved her and thought she deserved better. Afterward, I wasn’t afraid anymore. I was ready for the final transition. ‘Have you ever felt like you can taste the future? Like you know what’s about to happen? That’s how I feel. Back a few years ago, a friend here broke away from the officers who were escorting him and walked towards me in the dayroom. On instinct, I reached out through the bars and grabbed him. Tears stained his face from crying for hours during his last visit. I gave him a huge hug, and he kissed my cheek and whispered in my ear, “Roaddawg. You have the best chance to get free. Don’t let them win. Go back home to your family. Get free. Promise me?”’

‘Have you ever felt like you can taste the future? Like you know what’s about to happen? That’s how I feel. Back a few years ago, a friend here broke away from the officers who were escorting him and walked towards me in the dayroom. On instinct, I reached out through the bars and grabbed him. Tears stained his face from crying for hours during his last visit. I gave him a huge hug, and he kissed my cheek and whispered in my ear, “Roaddawg. You have the best chance to get free. Don’t let them win. Go back home to your family. Get free. Promise me?”’

Back in the hallway we continue until we reach the end. There is a door in front of us that leads to the electric chair and a door to the left that leads to the death row housing unit. The Sergeant taps it with his keys, and a guard who looks like he should be just entering high school opens the door.

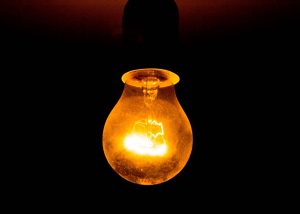

Back in the hallway we continue until we reach the end. There is a door in front of us that leads to the electric chair and a door to the left that leads to the death row housing unit. The Sergeant taps it with his keys, and a guard who looks like he should be just entering high school opens the door. After they leave, I look around for a light and spot a string in the corner dangling from the ceiling. I pull it, and a dim, 40-watt bulb comes to life. Roaches scurry everywhere.

After they leave, I look around for a light and spot a string in the corner dangling from the ceiling. I pull it, and a dim, 40-watt bulb comes to life. Roaches scurry everywhere. And so Mamou’s trial began. The O.J. Simpson trial was still fairly fresh on peoples’ minds – and Charles was a black man in Texas. The words of the Judge set the tone from the beginning, as he referred to O.J.’s trial that ended in an acquittal, stating that was, “not going to happen here. This is the real world. It is not California.” The Judge also compared being a juror to, “being a pallbearer at a funeral.” This was followed up with, “the State is going to seek the appropriate punishment in this case; that is, their claim that it will be the appropriate punishment, punishment of death.”

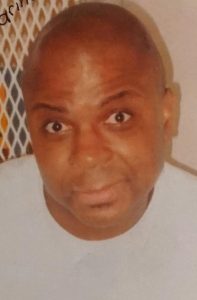

And so Mamou’s trial began. The O.J. Simpson trial was still fairly fresh on peoples’ minds – and Charles was a black man in Texas. The words of the Judge set the tone from the beginning, as he referred to O.J.’s trial that ended in an acquittal, stating that was, “not going to happen here. This is the real world. It is not California.” The Judge also compared being a juror to, “being a pallbearer at a funeral.” This was followed up with, “the State is going to seek the appropriate punishment in this case; that is, their claim that it will be the appropriate punishment, punishment of death.” The U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals has denied Charles Mamou’s last appeal, and he is currently awaiting an execution date.

The U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals has denied Charles Mamou’s last appeal, and he is currently awaiting an execution date. More than happy to oblige my ‘peers’, the Judge took all of sixty seconds to pronounce my fate. I already knew the sentence would be death, just as I had known the verdict would be guilty. “May God have mercy on your soul,” he concluded, before banging his gavel in an authoritatively dismissive manner, almost god-like himself.

More than happy to oblige my ‘peers’, the Judge took all of sixty seconds to pronounce my fate. I already knew the sentence would be death, just as I had known the verdict would be guilty. “May God have mercy on your soul,” he concluded, before banging his gavel in an authoritatively dismissive manner, almost god-like himself. Dammit! This heat! Sweat pours. The prison uniform I’m in is soaked. Sweat drops into my eyes, stinging me further. I squint and try to collect myself, so I can focus on the task at hand.

Dammit! This heat! Sweat pours. The prison uniform I’m in is soaked. Sweat drops into my eyes, stinging me further. I squint and try to collect myself, so I can focus on the task at hand. On July 19, 2018, my last appeal was denied. Not on the merits of actual guilt, for my case on appeal has never been argued orally. In fact, a recent study by the Houston Law Review cited my case and others for the opprobrious “rubber stamping” policy that Harris County and the southern appellate courts use.

On July 19, 2018, my last appeal was denied. Not on the merits of actual guilt, for my case on appeal has never been argued orally. In fact, a recent study by the Houston Law Review cited my case and others for the opprobrious “rubber stamping” policy that Harris County and the southern appellate courts use. …August 17, 2018. I have walked and counted eighty-eight full circles while contemplating my situation, which seems so surreal. Sometimes I wish it was as easy as John McClane made it seem as he stood bare foot, bleeding, bruised and scarred on top of Nakatomi Plaza screaming, “Yippee ki-yay, muther fuckers!” The good guys stood triumphantly for justice and made sure it rang loud and true.

…August 17, 2018. I have walked and counted eighty-eight full circles while contemplating my situation, which seems so surreal. Sometimes I wish it was as easy as John McClane made it seem as he stood bare foot, bleeding, bruised and scarred on top of Nakatomi Plaza screaming, “Yippee ki-yay, muther fuckers!” The good guys stood triumphantly for justice and made sure it rang loud and true.