Inside the confines of solitary confinement’s concrete cell, you have to make abnormal adjustments in a rather abnormal situation. Otherwise, your capacity to socialize atrophies, you wither up and die a social death. In this place, you’d better adjust and find creative ways of connecting and communicating, lest your emotions become hollowed out, leaving behind only a mere shell of your social self. I’ve been isolated on federal death row for fifteen years now and have learned some deaths are more inhumane than lethal injection.

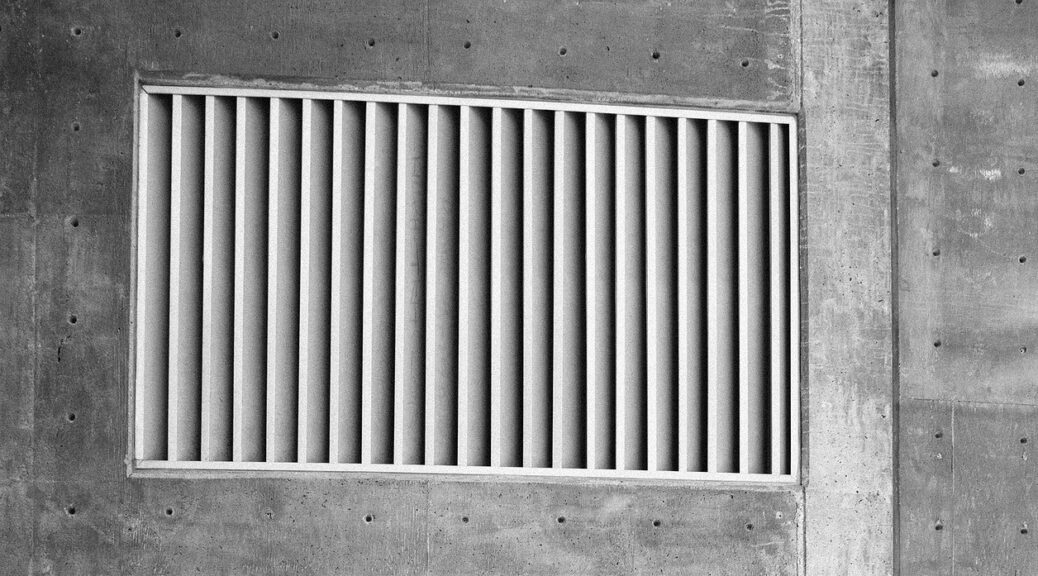

As long as there is an ounce of humanity left alive in you, a person is compelled to reach out and socialize, by any means necessary, even if you gotta yell through the solid steel door of your solitary cell. Or shoot the breeze, as I often do, with disembodied voices through the ventilation system.

In this four-storied, maximum-security building at the federal penitentiary in Terre Haute, Indiana, the ventilation system is a social lifeline. The grapevine of prison gossip and not-so-private confessions. The social network where mundane conversations go viral, carried through the vents of far-flung cells across the four floors.

Standing on my stainless steel toilet in my third-floor solitary cell, I shoot the breeze with voices from downstairs, my head close to the perforated vent on the concrete wall.

“I’m a white girl with tits and hips and ass,” a feminine voice lilts through the air ducts, cutting through the heavy male notes clogging up the airways. I would know that nasal, high-pitched tone anywhere, the way it emotes a joy uncharacteristic in this dank and dark place. It’s Bonnie.

“Call me Bonnie Grace,” she told me when we first met at the vent.

Bonnie lives on the second-floor, confined to administrative segregation, also known as the hole, which occupies the first two floors (federal death row occupies the upper two). In the hole, men who were once in general population are segregated and locked down in solitary confinement for various reasons, most of which have to do with disciplinary infractions or pending investigations. Bonnie is there for the latter. Or so she says.

I’ve been chatting with Bonnie since earlier in the day. I’d been pacing when I heard her yell up through the vent.

“Death Row!”

I ignored the voice at first, not sure who she was calling.

“Upstairs!”

Still, I paid it no mind.

“I know you hear me. Hear you movin’ round up there.”

Sounds travel through all this steel and concrete, and apparently, my footfalls were thudding upon the concrete floor, Bonnie’s ceiling.

Tugged by the voice, and ever yearning for social proximity, I stepped up on the toilet seat, put my ear to the vent, and that was the start of our social exchange. And no matter the subject, Bonnie tends to go off on tangents and promote her appearance, as if she’s taking selfies with her words. At this moment, she’s doing just that.

“I’m about five-ten, weigh about 150 pounds. Skinny. Long hair. Pretty…” She pauses, perhaps distracted or thinking, and then she says with gleeful pride, “And they say I look like the girl on Beetlejuice!”

“Beetlejuice? What?!” I reply, confused. I faintly remember that movie. I think the characters are phantoms or a version of living-dead, ghostlike, and I’m surprised that Bonnie sees this as a compliment. “WTF!” I comment.

A male voice interrupts us, “And she gotta big-ass nose too!”

“Oh my god!” Bonnie says, her signature interjection. “But I’m cute though!” She giggles, and I picture her admiring herself, her hand running through her long hair, flinging it in the air, giddy with all the social attention.

Bonnie is transgender, identifies as female, and takes hormones. “I take estrogen and anti-testosterone pills every day,” she informs us. And now she’s “a white girl with tits and hips and ass,” one of fourteen or so transgender residents at this all-male prison.

Bonnie’s legal name is Steven, out of Texas. Steven used to be part of a white supremacist gang. “I used to tear shit up,” Bonnie says, wilding out, fighting and stabbing, doing all kinds of “crazy shit” for the gang. But all along, she says, a part of her felt like a female.

Bonnie never tells me what led her to taking the prison psych evaluation, one of the first steps to transitioning inside the federal Bureau of Prisons. She just tells me about the process. She started transitioning less than a year ago, and her body has changed drastically. Or so she says. You never know what’s true at the vent. A person can be anybody, assuming whatever persona, catfishing and being catfished.

But I choose to believe Bonnie. I have to. In order to socialize. To stave off social-death.

After some time, I end the exchange, step down from the toilet, and plant my feet on the cold concrete ground. I resume pacing compulsively, one of the adverse effects of solitary confinement, and I immerse myself in the lingering warmth – the afterglow of social rapport.

ABOUT THE WRITER. Rejon is new to WITS, but determined to build on his natural ability with words, spending a good deal of his time on federal death row constructively using his creativity. I hope he continues to write, and I also hope he sends some of that writing our way. You can learn more about Rejon at his website: www.rejontaylor.art

He can also be contacted at: rejonltaylor@gmail.com

To learn more about Rejon’s case, which involved being charged at the age of eighteen years old and later sentenced to death, click here.

![]()

You are great at expressing lived experiences in a unique way from worlds, barely anyone on the “outside” bothers to acknowledge!

This is a most powerful testimony to the horror of a “Row of Death” that we Americans have allowed to be created in all of our names. Thank you as ALWAYS, Rejon, for using your gift to illuminate the darkness. May the world heed the warning! – The Thousands of Members of “L’chaim! Jews Against the Death Penalty.”