I am in prison because of my downward spiral of compromise, the gradual degeneration of my character and consequent choices. One compromise led to the next which led to the next, each one increasing the momentum of travel to and the probability of the next compromise.

My story is a tragedy, but not one of tragic beginnings. I was tremendously blessed to have wonderful parents and the advantages of academic gifting and opportunity, yet I still ended up in prison with a life sentence. How? Why?

My parents were incredible – loving, caring, kind, gentle, giving and honest. They taught and lived by their Christian beliefs of loving God and loving others. They prioritized the needs of others, supported without being overbearing, disciplined firmly yet without harshness, provided while instilling appreciation, and emphasized character, integrity, and respect for all.

I was academically gifted. Teachers frequently told my parents I was the smartest child they had taught. I won math contests and Science Olympiad events, participated in numerous opportunities reserved for top students, attended the prestigious North Carolina School of Science & Mathematics (NCSSM), and received several college academic scholarships.

I did not nose dive from the apex of the values my parents taught down into a cesspit of selling cocaine and carrying a gun. I descended one selfish, unprincipled choice at a time over several years. I entered the downward spiral by compromising with alcohol and marijuana. I drank alcohol for the first time while spending a week at the beach with a friend’s family. We went to a condo where more than a dozen people, all older, were hanging out. Drinking with the older crowd made me feel accepted and cool. Although I threw up and passed out, looking like a fool, I liked being part of the ‘cool’ crowd, naive with the dangerous desire to be accepted as part of the ‘in’ crowd.

The next year, the same ‘friend’ introduced me to marijuana, or pot. I did not want to smoke but did not have the courage to say ‘no’. My cowardice caused me to open a proverbial Pandora’s box of drug use. I liked being high on pot because it settled my mind, which was normally like an extreme laser light show, constantly on hyper-drive. Pot slowed the pace, allowing me to relax and feel normal for the first time. I eventually developed a daily habit.

My junior year began at NCSSM. Graduating from the residence high school for academically stellar students was my dream, but I traded it for nothing. Compromising by drinking and smoking pot cost me that valuable opportunity – it would not be the last one I wasted. Preparing to leave for college, I made another pivotal compromise, purchasing pot to sell.

For a while I could smoke pot and function well and still excel in school, even winning a math contest (Calculus) while very high. Selling pot allowed me to smoke every day, but smoking pot that much bore a critical side effect – it stole my drive. The exceedingly driven person with big plans, goals, and dreams, as well as the dedicated effort to accomplish them, was replaced by a distracted slacker.

As a freshman, I attended far more parties than classes, did more drinking and smoking pot than studying and learning, and added experimentation with other drugs (ecstasy, LSD, hallucinogenic mushrooms). I forfeited the academic scholarship due to terrible grades, having to attend summer classes to maintain eligibility.

I regained my academic focus and made the Dean’s List the next two semesters. Although the frequency of partying, drinking, and using drugs decreased (mostly on weekends), continuing to use at all was complete compromise. Two years later, I made another pivotal compromise, the terrible choice to sell cocaine. Quickly, I became addicted to the money, and began to view myself as a drug dealer. Adopting that identity led me to accept violence as a necessary part of the drug business.

Eight months later, my apartment was broken into and ransacked, drugs and cash stolen. My little beagle puppy, Bruiser, was left hiding under my bed, shaking uncontrollably. The break-in shattered my sense of security. I hated feeling afraid, violated, helpless. I wish I had responded by quitting the selling and using of drugs – forever. Instead, I responded by seeking revenge. Thinking I had determined the culprit, I organized a late-night armed robbery, however, the people we accosted were not involved in the break-in.

I thought striking out at someone, anyone, would make me feel less afraid and more in control, but the fear increased. I started carrying a gun everywhere, even to class. I always reentered my apartment with the gun at the ready, afraid.

Two weeks later my long, ever-worsening series of bad choices caused irreparable harm. Killing other human beings and being arrested for murder awakened me to how far down I had descended. I had the gun because for two weeks I carried a gun everywhere, because guns and violence are part of being a drug dealer, because using drugs can easily transition into selling drugs, because one compromise leads to the next. The overall direction of the compromises I made was steeply downward, but the incremental drop from one compromised choice to the next was so small as to be indistinguishable.

My parents and my gifts gave me the foundation for success, but I wasted both. The mistakes I have made are my own. I am solely, wholly responsible for my impulsive, immoral choices. I failed to learn from my mistakes, not only repeating them but making worse and worse choices. Smoking marijuana took my drive, selling drugs took my direction, identifying myself as a drug dealer destroyed my boundaries.

Now, I refuse to compromise on my values of honesty, integrity, compassion, diversity, and social responsibility. I know it takes only one compromise to enter the downward spiral, and I will never again re-enter the downward spiral of compromise.

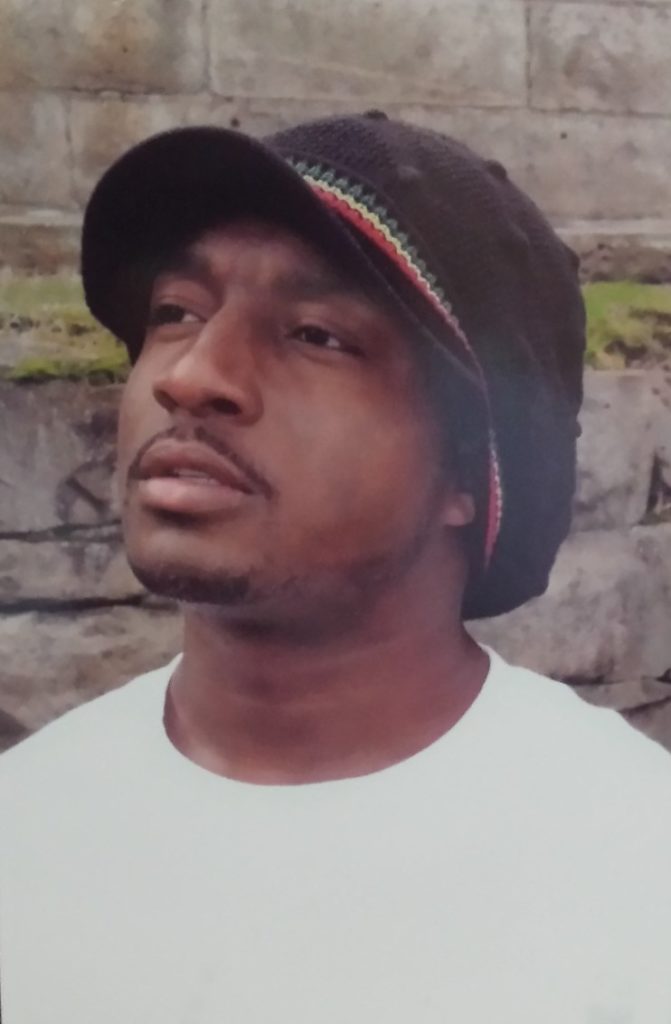

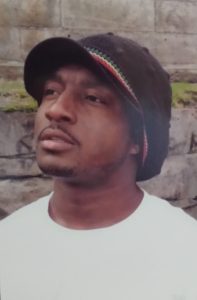

ABOUT THE WRITER. Timothy Johnson placed second in our most recent writing contest. Timothy has been incarcerated for nineteen years and is serving a life without parole sentence. He has a Bachelor of Arts degree in Pastoral Ministry with a minor in Counseling from the College at Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary; he serves as the assistant editor for The Nash News, the first and longest running prison publication in NC; he was editor of Ambassadors in Exile, a journal/newsletter that represents the NCFMP; he is a co-author of Beneath Our Numbers; and he has been published in the North Carolina Law Review (Hope for the Hopeless: The Prison Resources Repurposing Act https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/nclr/vol100/iss3/2/).

Mr. Johnson can be contacted at:

Timothy Johnson #0778428

Nash Correctional Institution

P.O. Box 247

Phoenix, MD 21131

Timothy Johnson can also be contacted through GettingOut.com

![]()