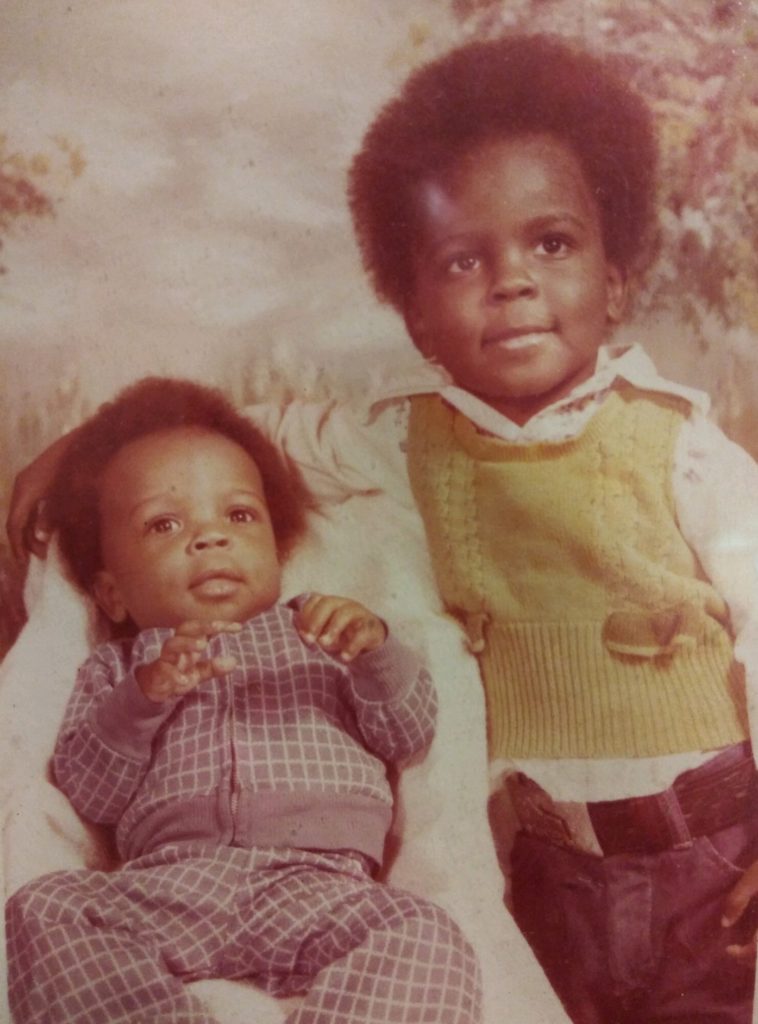

This story is for my brother, Ty. It’s about sturdy white t-shirts and durable black boots. Ty happened to be wearing both when he died. Today he would have turned fifty.

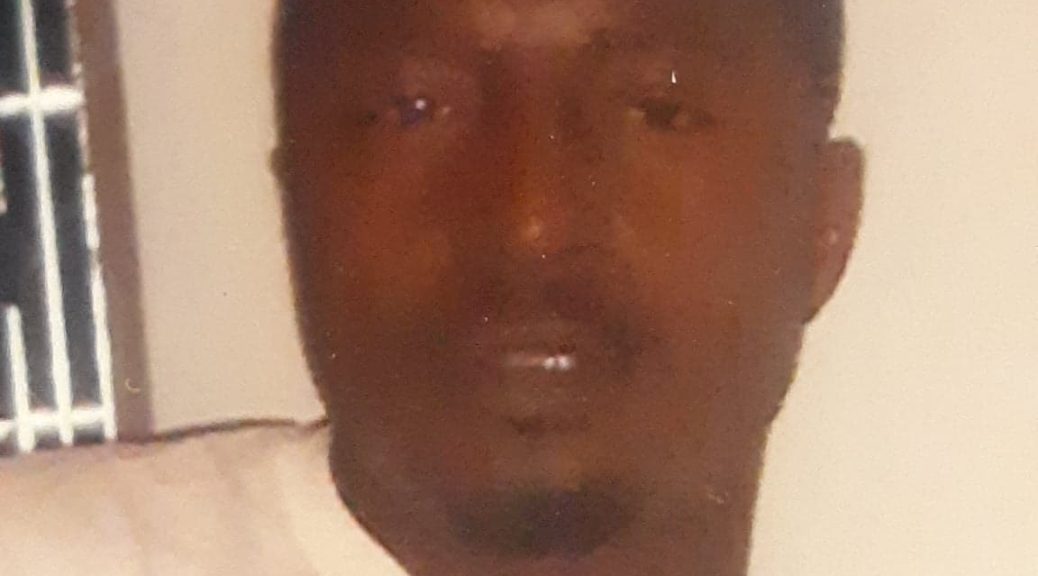

My brother died on a Harley Davidson. Actually the bike was on him when he finally came to rest face down in a lonely Idaho field. He had a broken neck and a B.A.C of 0.29. I imagine Ty smiling as he barreled headlong into the sinking September sun. Three short years have passed since my cousin erected a six-foot wooden cross at the crash site. If only the cool grey dirt could speak.

The rub is, Ty didn’t try to negotiate the familiar curve. There were no skid marks, just a beeline into oblivion. My brother had belonged to a Harley’s Only club. Over a twenty-five year period, he had ridden that Heritage Softtail from Mexico to Canada and everywhere in between. He died two miles from home.

After Ty’s body was cremated, my niece, his youngest, drove west to scatter her dad’s ashes across a windswept Oregon beach. That same day in Utah, her mother, Sue, Ty’s estranged wife, shot herself in the right temple with the 9mm Taurus my brother had inherited from me fifteen years prior when I was sentenced to life in prison. Sometimes I feel like I’m trapped in a soap opera.

I hurt a lot of people who loved me. One f those people was my little brother. His life was never quite the same after I abandoned him. When I selfishly planned and carried out a murder, I hadn’t thought about how the ripple effect would harm so many others who were left to clean up and live with my mess. How would things have been for them if I hadn’t imploded?

Somewhere between missionary and murderer, amid the muddled decades of my life, I lost a prized Hard Rock Café Las Vegas t-shirt to a karaoke groupie named Venna. By the time I realized she had take it from my closet and left a less-desirable Miller High Life tee in its place, she had moved away.

I ended up logging a lot of miles in that shirt. My brother called it a ‘wifebeater’ and laughed out loud when he first saw me wearing it on a fishing trip, and I spent a good deal of time trying to wear it out, everything from singing karaoke, gambling, hunting geese and ducks, camping, skiing, snowmobiling. Turns out Hanes makes a tough shirt – almost as tough as black Doc Marten boots.

Though my brother chose not to visit me in prison, he did write me one letter. That letter remains sealed and locked in a plastic box under my bunk. His daughter had enclosed the sealed letter with some photos she sent me after Ty’s sudden death. She said she had found the letter addressed and stamped in Ty’s business safe.

Exactly what that letter says, only my brother knew – at least until I find the courage to open and read it. I imagine myself dying of cancer and reading it just before my last breath.

Among the photos my niece sent, one stands out. Ty is standing on the deck of a chartered fishing boat off the coast of Mazatlan, Mexico, with a drink in his hand. One of Ty’s friends, Sean Bybee, used to call Ty Dean Martin, because he had some sort of alcoholic beverage in his hand at all times, or at least it seemed so.

At any rate, in that photo my brother was wearing the black Docs and the wife beater. He had them on when he crashed, and he wore them on a vacation with his family. I have to wonder if he wore those inherited items often, and if maybe he was reaching out to me in some way, maybe trying to somehow live vicariously. Maybe the articles of clothing were his bond with me. Lord knows a part of me resides in that shirt and those boots. No amount of laundering will ever remove every particle of mud, blood, sweat and tears.

It’s been said we shouldn’t judge a man until we’ve walked a mile in his shoes. I suppose this maxim applies to boots and t-shirts as well. I don’t know how many miles Ty logged in them, but part of himself is surely woven into their fabric. Too bad clothing can’t speak.

They say God works in mysterious ways, sometimes tragedy benefits us unexpectedly. Surely Christ’s gruesome death on the cross benefits all who believe that his blood has washed away the stain of sin. That said, when Ty died, his funeral notice was posted online. My estranged son of 23 years saw it and drove nonstop from Phoenix to see the uncle he had never met before he was cremated. Zac hit the jackpot when he walked into that Mormon churchhouse and met the hundreds of people gathered to celebrate Ty’s life. He met Ty’s daughter and all of his cousins, reunited with his grandmother, and felt the ground shake in smalltown Rigby, Idaho, when 127 Harleys idled down Main Street in tribute to my kid brother.

Two weeks later Zac walked through the doors of this prison to reconcile with me, the father he hadn’t seen or spoken to since a memorable fishing trip at age five. When he came through the visiting room door two days before my third grandchild was born, accompanied by the other two and his beautiful wife, I was both proud and sad.

My elation was bittersweet because it took Ty’s death to bring about this reunion, and I realized Ty would could never walk through that door, only the black Docs and wife beater Zac had worn. My mother had appropriately presented the items to Zac after they had been removed from Ty’s lifeless body. A stranger had written the first chapter in the story of that white t-shirt. Ty and I had added chapters of our own to the saga and woven the black boots into the narrative. Now it will be up to Zac to continue the legacy. His chapter might be somewhat tame in comparison. Zac is a doctor now and a staunch Mormon to boot. He doesn’t gamble, ride motorcycles or drink beer.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR. We recieved this piece from Mr. Briggs as an entry to a previous writing contest. Every judge was impressed with the strength of Mr. Briggs’ writing as well as his ability to express himself. He was not chosen as a winner in the contest because his work didn’t exactly fill the prompt – but his work is exactly what this site is here for. I hope we hear from him again. And I’ll aways wonder if he ever opened the letter. Mr. Briggs can be contacted at:

Todd R. Briggs #66972

Idaho State Correctional Center, G Block

P.O. Box 70010

Boise, Idaho 83707

![]()