Present Day, Death Row.

I recently studied a photo of Stephen Hayes’ exhibit, 5 lbs., featuring a wall of dark dinner-plate-sized frames, each filled with brass shell casings. Emerging from the bullets, hands that seem to be reaching from underneath – or maybe surging up through – a flurry-flood, breaking the surface like drowning men and children.

The first message is cerebral. As a series, the lots of dinner plates and lots of hands suggest a widespread pattern of violence.

The second message is emotional. Wide-spread fingers and clenched fists speak a language I recognize – DESPERATION – showing that ultimately each of us suffer fear and death alone.

I’ve been incarcerated twenty years, but even now, at forty-one, my breath quickens as if those fingers are mine, screaming at me from the past. When I was twelve and living in the projects, I suddenly realized that before I turned thirty, I’d either be dead, serving a life sentence, or waiting to be executed. When I told my homies, they looked at me coolly, like I’d pointed out some obvious and natural law, the way gravity pulls all bodies toward earth’s center.

February 1993. The Projects.

You need to call the cops… What? I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. Call the cops! That was taboo in the projects; we all knew the consequences. My homie’s mom draped her heavy arm around my shoulders, lifted my chin to examine tonight’s damage. I had thick red welts from where my dad’s fingers had encircled my neck.

“George, sweetie, I know we not s’posed to, but if you don’t call the cops, yo daddy gon’ kill you or one of yo brothers.”

She said it so tenderly, I started sobbing again. Though I was scared of my dad, I was terrified of the po-leece.

As boogeymen, police had supernatural powers to make people disappear. Adults threatened children with them, like, if you don’t take yo li’l ass to bed, the po-leece gone take yo li’l ass to jail. Our campfire stories centered around THE LAW – run-ins with them, running from them, getting captured by them. I didn’t want to call the cops; I didn’t want to die either.

She dialed, then pressed the cordless phone to my ear. A stranger’s voice said, “9-1-1, what’s your emergency?”

Finally, desperate, I told on my dad. I told about the years of beatings, the broken bones, how he’d tried to kill me, that my brothers were still in the apartment with him.

By the time the cops came to rescue me, I felt better. I figured my brothers and I would either go live with our mom (wherever she was) or go into foster care. Either way, we’d escape the projects and our dad.

The cops were kind. Both were middle-aged, one White, one Black. They took me to confront my dad who stood shirtless on our stoop, smoking a cigarette. He smirked when he saw me walking up between two brawny officers.

We stopped about five feet away. One of the officers rubbed warm circles between my shoulders. They told my dad all I’d said, then got quiet. My dad dropped his cigarette, stubbed it out with his bare heel, then growled, “Yeah, I did it. All of it.”

The guy on my right looked down at me a couple seconds, then back at my dad. Then he pressed me forward and said, “Well… you must’ve done something to deserve it.”

The cops nodded to my dad, then walked away saying, “Have a good night, sir.” My dad sidestepped as I hung my head and went inside to rejoin my brothers.

Sometimes, after that night and just prior to or following a beating, my dad would drag me by an ear to the kitchen phone and thrust the receiver against my head. “Here, call for help,” he’d say, chuckling. I’d close my eyes and click the phone back into its cradle.

March 25, 1993. The Projects.

I’d turn twelve at midnight. I lay on my bed monitoring the sounds inside and outside the apartment, anxious. The corner where our sidewalk bordered our parking lot was a prime hangout spot for dealers, users, prostitutes. Every night I listened to car stereos thumping, people laughing, bottles bursting (sometimes through our windows), the undulating tones of an argument that ended with the slaps and thuds of fists on faces – or gunshots. After years of living here, like an inner city lullaby, these hypnotic sounds soothed me, rocked me to sleep each night.

But tonight was initiation night. Despite having lived here so long, my family still wasn’t accepted. At first, it was because we were only one of two nonblack families – my mom, Korean, my dad, White. Also, my dad tried to keep my three brothers and me within shouting distance at all times, locking our doors for the day once the sun went down. We were day-shift people.

During the day, the projects seemed mostly abandoned, withdrawn, guarded, like my dad. Though we lived in the ‘hood, we weren’t of it. My brothers and I were baited into fights every day. People stole our towels, socks, even underwear off our clothesline; threw mud, burnt grease, piss and shit on our drying bedsheets. All of it screamed, YOU DON’T FUCKING BELONG HERE!

So, I’d decided to join them. My friends would help initiate me into the real ‘hood life. What had me on edge was my dad. I didn’t know the term schizophrenia yet; all I knew was that he was crazy, unstable, violent.

He also oscillated between narcolepsy and insomnia. Most nights, he’d prop up on the couch in our living room, in pitch dark, chain smoking Winstons… until he passed out for ten or fifteen minutes at a time. I was waiting to hear his heavy breathing turn into snores. I needed those loud snores if I was going to sneak out – and later, sneak back in – under their cover.

I was startled upright by screeching tires and, “FREEZE!” A stampede of feet slapped grass and cement and rattled hedges outside my window as shadows flitted past. A minute later, several ambled back and became menacing silhouettes outlined by strobing red and blue lights. They laughed among themselves.

“…like roaches!” one of them yelled.

Though the cops had cleared the corner, everybody knew the crowd had simply relocated to one of the other parking lots. As kids, before we ever committed a crime, ‘hood life taught us to scatter reflexively at the sight of a police cruiser, period. It was a joke, or a dangerous form of Tag. You’re it.

My dad’s lawnmower-snores rumbled through the apartment, unbothered by the ritual outside. I laced up my sneakers. I was tired of being treated like an interloper. I knew my family was too poor to move anywhere else, so I crouched on my bed, listening to dad’s steady snores, then climbed out my window.

Present.

Looking back, that was around the time I found the first gun I’d ever own, just laying in the grassy field beside my parking lot – the same field we’d cross to get to the bus stop, or when running from cops.

Last week, I heard on the news that someone there did a drive-by shooting, hitting three teens standing on the sidewalk near that bus stop, across from the police substation. The assailant got away. It seems nothing has changed except the generation. I can’t help but wonder – was there so much crime, really, because our way of life in the projects was anti-police, or were we behaving criminally because police were anti-us, and we didn’t have anything to lose?

For me, the art exhibit photo merges past and present desperations. In the past, perhaps, one of those hands is mine, reaching toward the police for help. Presently, those hands seem to embody the pervading fear of police that people of color have – hands held up defensively, pleading, STOP… ENOUGH… WAIT… JUST FIVE MORE MINUTES…

It’s as if those hands know that to keep their freedom and bodies intact, while facing impossible odds, they must learn to part the sea. They’ll need a miracle.

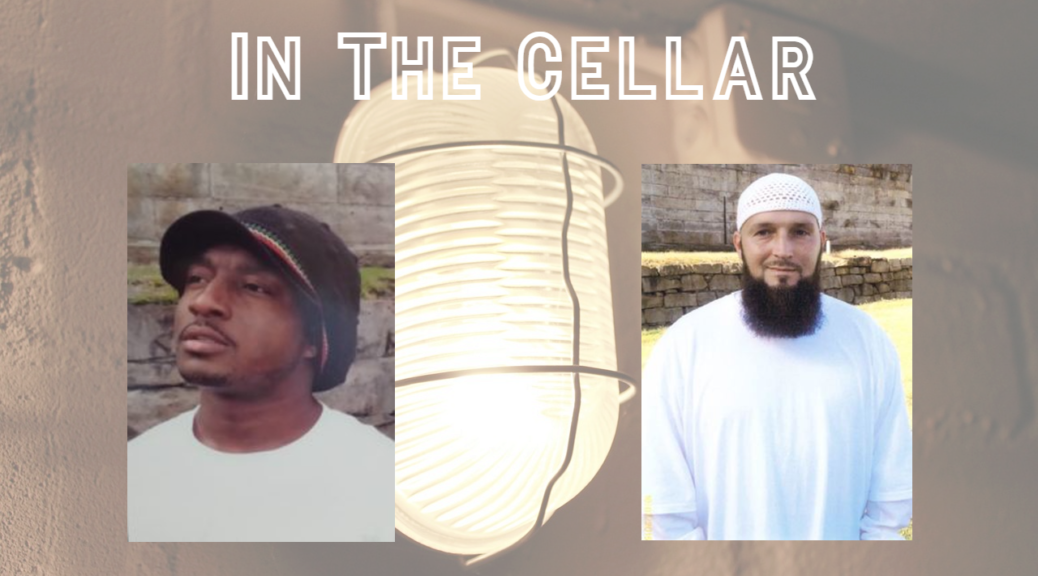

ABOUT THE AUTHOR. George Wilkerson is an accomplished writer, poet and artist, and I am always grateful to share his work. George is the author of Interface and Bone Orchard, as well as co-author of Inside: Voices from Death Row and Beneath Our Numbers. He is editor of Compassion, and he has had speaking engagements on multiple platforms, adding to discussions on the death penalty, faith, the justice system, and various other topics. George’s writing has been included in The Upper Room, a daily devotional guide, PEN America and various other publications. More of his writing and art can be found at katbrodie.com/georgewilkerson/.

George Wilkerson can be contacted at:

George T. Wilkerson #0900281

Central Prison

P.O. Box 247

Phoenix, MD 21131

He can also be contacted via textbehind.com

![]()