Charles,

Hey, I’m not sure how much love you get through the mail, brah, so I thought I’d push some your way. It’s free, so why on earth wouldn’t I give it away? You only have to pay for it, if you refuse to pass it on. Funny the truths that you’ll trip over in these little cages, right?

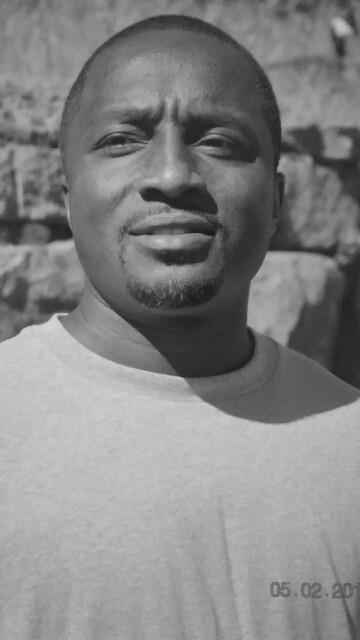

My name is DeLaine Jones, and I’ve been on lockdown for the last thirty-three years. I’m also a writer for WITS. I’ve been reading about you for awhile now, meaning to get at you, but only now making the time. I’m not sure if you’ve read any of my work, but I’d like to write a piece to you.

I’m not looking to gain from the war you’re fighting to take your next breath. But I don’t just look like this, I’m really black! I speak, read, watch and write through these bars, into and about a struggle that I can’t physically take part in. But even as I gasp and choke my way to hope… I see you, brah!

Back in the dayz when we were in chains on the other side of these bars, we as black people used to speak to other black people whom we had never met. Not simply as a courtesy, but from a genuine concern, a want to help someone who’s chains, pains and scars resembled our own. I personally believe that if I can in any small way, shape, or fashion, help you be heard – it is the reason for my ‘hood card’. As I started out, you’ve got to give it away to keep it coming in, brah.

I’m serving ninety years for crimes I committed when I was seventeen years old. Though I don’t have a date to die, I too know the value of hope, how being touched can alter the quality of the air you breath. That at times it’s easier to let go rather than fight to hold on for another day. That at times, we need to be held on to. Today, I’ve got ya, brah!

So, this is us passing on an old dirt road in the deep South… “What’s up blood, you good?” – meaning, if you need me so you can hide for a awhile and rest till you are able to run again – I’ve got you. I’ve got a scrap or two of food that’ll tide you over too! “You good, cuzz-in?”

I’ve only ever written about my life and the people who’ve passed through it. It’s crazy how I can hear their voices at times when I write. Has that ever happened to you? For me, it comes when people encourage me. It’s then that I hear my granny say, “We are all that we’ve got.” Only the encouragement comes from some place other than my blood. So I expect the givers of those words to give up at some point, to wake up tomorrow and they too will have ‘passed through.’

No family, I’m not in the same part of the river, but I can see you being drowned from where I’m being held down. Those words are needed, welcomed even, but as we both know this is way too much water for either of us to be tryin’ to drink!

People will try to rob you of your anger, telling you to be ‘be calm’. But as a black man in the system, ‘be calm’ is code for ‘stop struggling so that I can kill you!’

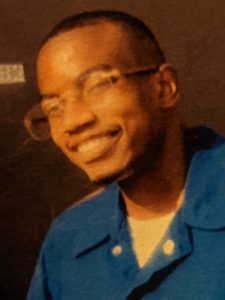

Charles, I’m not sure if I’ve ever met an innocent man before. But I do know that they hand out far too many of these sentences without revealing every bit of information that they can get their hands on, laying it out for all to see, rather than allowing the D.A. to decide what it suits his case to present. Who knows a diamond’s worth until it’s seen? Under magnification at that!

It’s the systemic contradictions and racist collusions that gall. To be willing to seek a mans’ life as payment for a life – but to be negligent in that you don’t turn over every single stone in your quest, this in respect of the very priceless substance you claim to hold so dear.

Life!

Charles, I call the collusion systemic and racist because its not an accident that you’re black nor how you’ve come to be on death row. Your legal counsel never bothered to ask basic and obvious questions that would have lead to the truth. How does anyone who’s passed the bar in this country allow testimony about a sexual assault without the challenge of a rape kit? Evidence? Examination? Something!

Your counsel stood by and let that become part of what the jury heard and a fact, agreed to but not supported by evidence. The D.A. knew it and your counsel had to know it. But it gets better!

The medical examiner shows up without the physical evidence he gathered! Doesn’t even mention it. The D.A. shows up without the only physical evidence that can suggest that you didn’t, in fact, commit the crime. The Judge allows it all to happen, and your counsel, none of the sworn officers of the Court, think that it is note-worthy? Each of their perspectives center on the same physical evidence, which happens to have been collected in a rape kit, and none of them bother to produce the only existing physical evidence? And we ‘the public’ are to simply ignore the obviously choreographed farce?! Allow you to kill a man based on the above?!

A lone woman from Virginia went to Texas and found the rape kit twenty years later. It was never lost.

Charles, I have no idea at what temperature the naiveté of white people is burned away. Many seem baffled as to why black men would be so desperate to escape the mere presence of police if they were not guilty – as if guilt justifies murder.

For some, it’s the walk on the sun that has fried the brain’s ability to believe what it’s seeing, a quick flicker of a thing that is banished in a single blink of the eye. In that glint, they reach for justification that makes them okay with themselves and cools their soul. They can then dismiss and pardon and excuse themselves.

In that flicker, they find themselves on an old dirt road in the deep South, passing a person who’s breathing hard from running. They see the pain of the other’s soul reflected in eyes they quickly turn away from, denying them to be like their own. They don’t offer the other a place to rest until they can run again, a scrap of food to tide them over. “You good, bro?” only crosses their minds.

In that encounter they find themselves face to face with themselves. Their guilt isn’t about Jim Crow or slavery or things of the past, but what happened this morning. The modern day lynching of a black man that took place in a courtroom in Texas. But hold tight, brah! Charles, be encouraged! If you need me so you can hide for a awhile and rest till you are able to run again – I’ve got you. I’ve got a scrap or two of food that’ll tide you over too!

ABOUT THE WRITER. DeLaine Jones is not only an amazing and thoughtful writer – he displayed his heart and compassion in this piece. He was never asked to write this, simply sent it in with no prompt at all.

As a WITS writer, he receives pieces from other WITS writers when possible. In that way he came to know Charles Mamou’s story, also a WITS writer. I can’t think of a better piece to post this holiday season. As always – I look forward to hearing from him again. Mr. Jones has served 32 years for a crime he committed when he was seventeen years old, a juvenile. He can be contacted at:

DeLaine Jones #7623482

82911 Beach Access Road

Umatilla, OR 97882

![]()