My life was over. I could tell from the looks on their faces. No more was I Duck, Dreadz or EyeGod – brother or son. When I stepped into the courtroom, I was nothing. Blank, a clean slate, yet covered in the dirt of my past, so much so that the me I knew disappeared under the grime. And now I was just a stage show, a star villain in a real-life tragedy that left a man dead and others calling for my execution. There was no going back after that. It was as sure as that prickly feeling nagging me for the first time ever – whether good or bad – my old life was gone.

I was dressed in a flannel button-up and beige dockies – the first clothes I’d worn in eleven months besides jailhouse jumpsuits and prison browns. I was supposed to look civilized, already mitigating before the judgment began. My black and white Airforce sneakers and outfit didn’t match, but neither did the stories match that were told about me, so my clashing wardrobe was keeping with the theme. Still, I wanted to explain away my uncoordinated attire and tell the jury that I had better clothes to die in, but silence was the etiquette when trying to elicit sympathy. So, I didn’t speak. I didn’t tell them that they had the wrong man. I hoped my sober face, mismatched clothes and nappy Afro said it all – I didn’t kill John Rushton.

I was escorted by a sheriff who held my elbow in a grip that was bolt-resistant. I didn’t blame him for thinking I would run. I’d done so twice before. Seated at the table were my defense attorneys, looking busy as they shuffled through a mess of papers, cutthroat attorneys whose aim was all wrong since they kept trying their tactics on me.

“One juror is your mother’s coworker? …that could work in our favor.” “Oh, you weren’t supposed to pass the IQ test,” and, “Have a look at the victim’s body and tell me… does it make you wanna sign a plea?”

They were persistent at trying to invoke a sense of guilt and responsibility in me – now if they could just be as committed to defending me. My eyes swept over the room in search of my mother. I didn’t want to lose her face in the crowd. I was comforted by thoughts of my mother during those cold dark nights in solitary confinement when I took myself to trial. I found her amongst the section of the pews reserved for those in sorrow, the woman who nursed me when I had a cold or scraped my knee was now watching a capital boo-boo unfold that her Band-Aids couldn’t fix. Her face looked unendurably strained, like commercial glass pelted by a storm’s debris. A face that had long ago shattered, but one she put back together for my sake. She was trying to be strong for me. But who was going to be strong for her? I picked my head up and acted like it all meant nothing.

The jurors were seated side-by-side in a wooden box, their arms and legs shielded from view allowing them to fidget anxiously in private. I was told that they were a panel of my peers, but I’d never seen any of them on the corner selling dope, so to me they were strangers, there to judge my life without repercussions to their conscience. They were decent-looking folks who all claimed to be Christians but said they could come back with a penalty of death. I figured they were reading from the Bible with a typo that read, “Thou shalt not kill, unless…” They appeared like the heads of a mythical creature, inhabiting their wooden box as they waited to lay waste with their pens and perspective. I made the mistake of looking over at them and many glared back, but only one of us turned to stone.

The door swung open and in walked the judge with a blond comb-over hardened with gel. He was a small man sporting a giant personality, his shoulders raised and eyes steady as he flowed across the room draped in black, a good place under which to hide his personality. He took to the stand and seized hold of his gavel, the same one from the day before when he struck down my attorney’s motions. I sucked in a deep breath of air and held it there bracing myself for the impact.

The judge spoke fancy gibberish that made some eyes narrow with wonder, lawyer talk for ‘now’s the time to tell me what this boy has done’. The prosecutor lead off by saying he could prove I carried out the murder. I was immediately concerned, more than I already was – his accusation sounded like a fact. Mild mannered and with an affinity for neatness, he straightened his tie and said he would ask the jury to kill me. I could tell they were thinking about it – they hardly looked my way again.

My attorneys continued their paper shuffling while pitching whispers at one another. Every so often they gave me a reassuring grin – somewhere in those papers was proof of my innocence. They, in turn, gave a compelling opening argument to rival the prosecution, and for a moment I was proud to have such prestigious white men speak adamantly on my behalf. The judge banged his gavel signaling the end of the preliminary warmups as the real fight was about to begin.

The prosecution called on several law enforcement officers to take the stand, each laying out the credibility of his case. It was a professional exchange that grew more intense the longer the inquiry lasted. For the most part I was able to follow along, but I kept getting tripped up in the terminology so I paid attention only when they mentioned my name. By the time it was over, my word was already shot. These were men and women with guns and integrity for the law, and all I had was a story full of holes.

During the cross-examination, my attorneys recovered, though they didn’t fill in any holes but rather created some of their own by asking questions that warranted answers scientifically in my favor. But I didn’t care much about the DNA, as I knew it wouldn’t point to me. I was waiting on the testimony of the two people I knew – Jed and Udy.

Udy was a neighbor whom I’d known since we were kids. We were in-laws since we were born. He was an impressionable teen with a propensity for trouble – but hell, so was I. I’d been to prison twice before and talked with Udy about what it was like. I tried to steer him on a different path because he was like a brother to me. I’d made whole-hearted attempts on several occasions to keep him out of prison, so it was not only shocking for him to say I encouraged him to do a robbery – it was insulting.

Jed was a different matter – he was trouble personified yet a charmer masquerading as civil. He was a master manipulator which didn’t bother me before because we were blood relatives, and I looked up to him. But now he was claiming I confessed murder to him and that he reported me because it was the right thing to do. Bullshit! Jed was up to something, and I needed to look into his eyes to figure out what.

Udy took the stand wearing a dress shirt and tie with a fresh buzz cut and a youthful face, the kind of look that made it hard to discredit him. He testified to the same story he’d made previously in a statement to the police, except now the details were extensive. He sounded so believable that I wanted to puke. His lies were so sickening that they made me regret our friendship, yet strangely enough my anger wouldn’t keep me from feeling sorry for him.

Then Jed, who was kept sequestered to preserve his grand entrance, burst through the door, all mad and determined. Part of me was hoping that, as family, he would be bound by a code of ethics to tell the truth. But swearing on the Bible was like swearing on a matchbook to Jed because his story was even crazier than Udy’s. It was all the same I guessed to a Christian jury who believed God would support their vote for death. He gave such a heartfelt testimony of how much it hurt him to have to turn his cousin in, claiming he did it because it was the right thing to do. It was then his motives became obviously clear. Jed had no allegiance to any higher power – his God was self-preservation.

I could hardly wait to take the stand on my own behalf and tell the jury what really happened. There were corroborating witnesses to vouch for my whereabouts – I was off selling drugs that night. I didn’t own a gun. I wasn’t hard up for cash. I didn’t make any robbery plans. I’ve never killed anyone in my life, and I certainly didn’t confess to doing so. Still, the jury would want to know why my cousin and friend said I did those things, and for that – I had no answers. But the burden of proof wasn’t on me, right? Right?

Turns out, I wouldn’t get the chance to testify. At the last minute my attorneys advised me not to, assuring me that putting on evidence would ruin any chance of a favorable verdict. “The DA has the burden of proof. You heard them, Terry – they didn’t prove a thing. If we start throwing crackheads on the stand, it’s gonna look like we’re grasping for straws and they’ll find you guilty for sure. Besides, our putting on evidence would mean we’d have closing arguments first, and I want to argue last.”

I didn’t give a damn about straws and arguing strategies. I wanted to fight for my life. But I also couldn’t afford to piss off the only two men assigned to defend me and I was unfit to deal with their tantrums, so I stood up in open court and waived my right to present evidence. It felt like I killed myself. It took the jury a few hours to decide that any man who won’t confront his accusers is likely guilty. As they read the verdict I fiddled with the fabric of my clothes, so I wouldn’t forget what it was like to be me.

The rest of the trial was a haze of legal formalities that grew limbs and sprouted into the death penalty. While all the mitigating, paper shuffling and scrounging was going on, I was still trying to figure out how I got there. A man was dead. I was accused. I didn’t say shit to the jury – and just like that, my life was over. The numbness softened the blow, the sentence not affecting me like I thought it would – that’s what happens when you judge a stone. I was afraid that at the mention of the word ‘death sentence’, I would keel over and die. Nope. They were saving me for the lethal injection. I wondered about the jurors, when their lives were done and their day of judgment came, what would they do when they learned that they were wrong?

As I headed to Death Row in a prison van, my wrists and ankles bound by a chain, I took in the sights around my hometown for the last time. I cried not because I’d lost my life to injustice. I cried because they took my name.

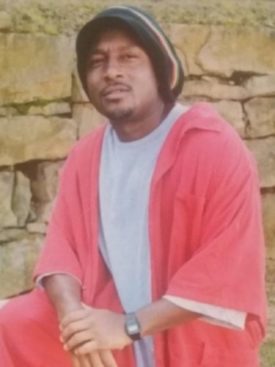

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Terry Robinson writes under the pen name ‘Chanton’, is a member of the Board of Directors of WITS, and heads up a book club on NC’s Death Row.

He has always maintained his innocence, and WITS will continue to share his story and his case. Terry continues to work on his memoirs, as well as a book of fiction, and he can be contacted at:

Terry Robinson #0349019

Central Prison

P.O. Box 247

Phoenix, MD 21131

OR

textbehind.com

![]()