When my ex-wife sent me divorce papers, it was a hard day. I hadn’t seen or spoken to her in more than three years, and I was hurt she had broken her promise before God. But I came to understand… eventually. I was unable to free myself from this hell after nine years of marriage. I’m happy to have been touched by that woman, to have breathed that air. I can’t be mad.

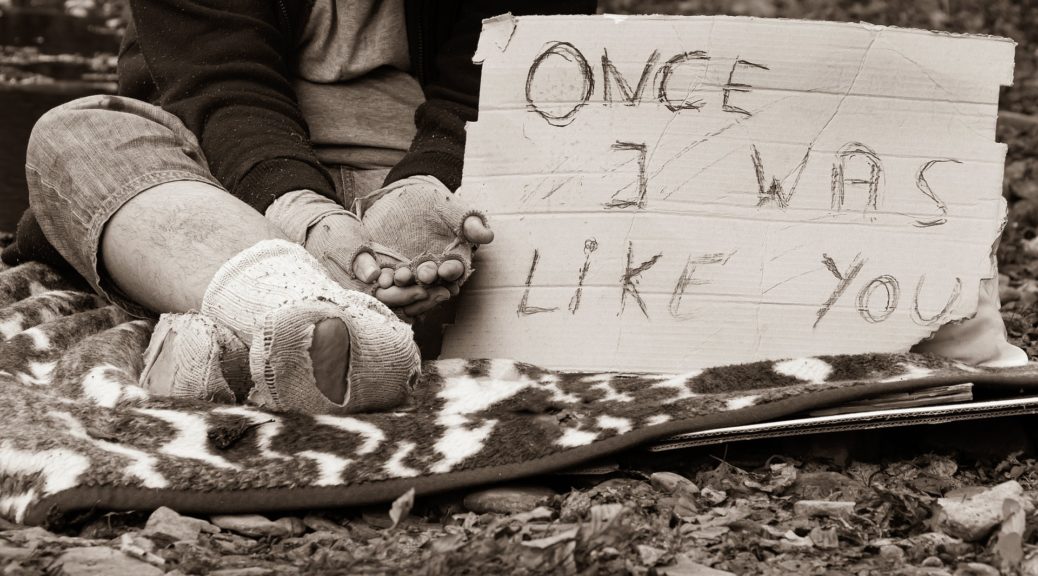

Food, water and touch – I don’t care who you are, where you come from, or what your socio-economic status might be, those are vital to living. Time in prison is meant to deprive you of touch, being loved. It’s meant to cut others off from confirming your worth and value despite your faults.

I first started getting locked up when I was about twelve. Truancy was a crime that they put kids in a cage for. Back then it was my grandmother’s touch that mattered, her showing up to say, “That one over there? You can’t have him! I want him back!” Value. Worth was set.

I didn’t know what it was to condition someone back then, purgatory. It wasn’t until I had served three and a half years on twenty-three hour a day lockdown, one hour out per day, and found myself adapting that I panicked. I was a mess when I got out. I still have trouble being in large crowds. I had to go to Toastmasters to regain the confidence of speech. To this day, my reactions to conflict tend too violent at first blush. It’s hard to shake years of depression and the ‘you ain’t worth shit!’ mentality of ‘fuck it!’ after that much time of having no contact with anyone. I’ve gone up to ten years without family or friends, without touch.

I’ve lived most of my life on lockdown, over more than twenty years total. It’s done things to my mind and spirit, killed parts of me in an isolated cage, witnessed only by God and myself. Vital pieces of me the young man didn’t know that the old man would need, the two of us at war over what shape or form my soul, my person, would eventually be. Deprivation of touch is an old slavery tool, tried and true, meant to reshape the human spirit.

It’s a hell of a thing to question your worth because of conditions, situations and an environment designed to deprive you of an affirming touch. People are paid to make this happen?

I’m guilty, you say? I agree, I am. I’m also remorseful, grateful, humbled, able and flawed. I’m broken but not destroyed, and I’m worthy of more than judgment and fear. I’m so much more than guilty. I’m a man in need of a woman’s touch.

Many who are far more eloquent than I have written about the power of contact and connection, but I’ve been curled up on my bunk in tears for lack of her. That need has broken my heart in a hundred ways, as I call out to God for her touch, only to curse Him for not moving fast enough! I’ve had a thousand conversations designed to return love to her, only to hear myself speaking out loud to no one I’ve ever met or knew to be real, a conversation based on a freedom that may never be returned to me, that I may never recapture.

A product of this battle is an intense focus on myself to the exclusion of others, withdrawing into my own pain and rejection, knowing to touch or be touched by another comes at a great risk, much like a child punished for his love of candy bars to the point that he fears the glorious taste of chocolate. A man adrift in a sea, fearing the dry, sandy shore will not return his feet once they are covered.

Just as fear and desperation are the greatest of motivators, hope and desire are the coinage used to barter passage from the what was of yesterday to the dream board of tomorrow, and all you have to build on is the now – this moment of contact, of being touched.

I met her through a friend, by all accounts a beautiful soul, person and woman. Brave and courageous beyond believe, she flung herself forward with an open heart, one broken by some who were forever cutting the wheel in a game of chicken when she has always too much of a woman to bluff. Then, as such stories go, she’d blame herself for not being enough. It’s crazy the way the brave are willing to carry the faults of others as their own, despite the facts.

Loneliness? Depression? Sure, we’ve both seen those, but as long as I’m 100% the man in her life and she fills mine to the brim with her touch, we’ll change the quality of the air in this hell we find ourselves in.

Is it enough to simply survive the hardships of life? My world is a place of hot ash and fire, metal and concrete. The real danger for her is that I’ll never see freedom. She could spend the rest of her life sharing breath with a man she can never reach out to in the middle of the night. But do I be the man she needs in her life, tempt her, only to then reject her in the name of sparing her the ‘possibility’ of future pain? At the expense of her touch in my life? Is that a noble sacrifice or me fearing the sand won’t give my feet back?

Everything in life should be insurable! There are too few guarantees in this world. Identify who you like and need, and fight longer and harder than anyone else for who you must have. Give your all to see that someone grow and prosper, as they tend the same garden in your life. This is how you wed to someone, know and become known by someone. Shared contact. Touch.

Sharing dark moments of my life on paper gives someone else permission that was never needed to clench their fist or soften their hearts – or both. For some, its teeth and claws, for others, its writs and laws, maybe a business plan, but for yet others – it’s a helping hand to one not your kind, color or even your friend, because trouble is a promise and nobody gets it right every time.

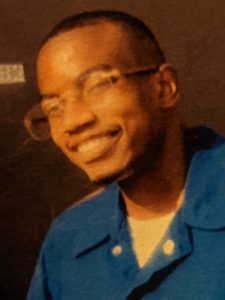

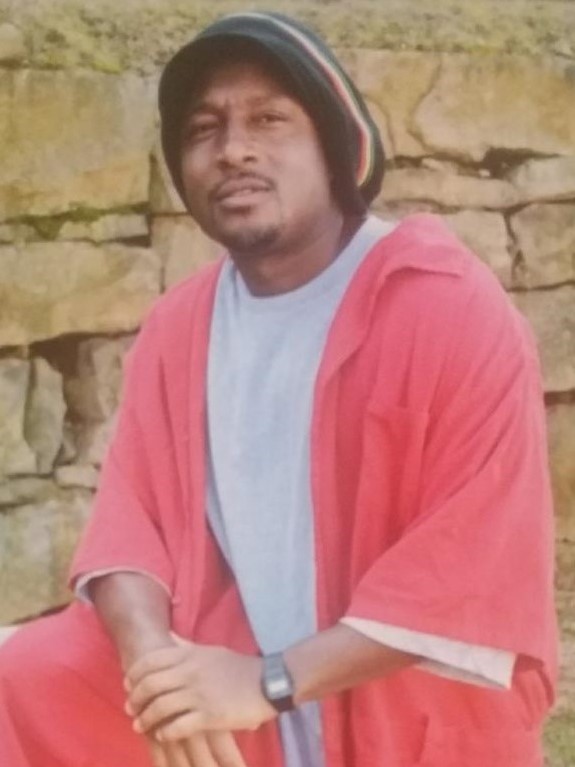

ABOUT THE WRITER. DeLaine Jones has, once again, risen to the occasion. He his our second place writing contest winner. He is a great talent, and we are honored to be able to share his work here. As always – I look forward to hearing from him again.

Mr. Jones has served 32 years for a crime he committed when he was seventeen years old, a juvenile. He can be contacted at:

DeLaine Jones #7623482

82911 Beach Access Road

Umatilla, OR 97882

![]()