Dear Bear,

Writing this letter is harder than I thought, but for you – it is worth trying. I’ve never known anyone to write a dog before. Maybe that’s because no dog has ever meant so much to someone. It’s crazy to think where we both ended up – you buried somewhere in an unmarked grave and me worse off than dead. That’s what Death Row is, Bear – a place between life and death. It’s where people are deliberately kept alive long enough to anguish over the fear of being executed, tormented until all peace of mind is used up. Only then are we ripe for slaughter. How I got here on Death Row is too long a story and too depressing for the details – but, do you remember the guy next door whom I was cool with? …turns out he wasn’t so cool. I may never know why, but he accused me of taking another man’s life during a robbery. Can you believe that? That’s why I couldn’t get home.

Anyway, getting back to the purpose of this letter. Bear, I had a dream about you just now. Hold on! Before you start bouncing around with those lofty cartwheels of yours, you should know it wasn’t a good dream. In fact, it was probably the saddest thing I’ve ever dreamt, even though part of me wishes I could’ve stayed under. I woke feeling unfulfilled, like when waiting your whole life for something to happen, then realizing five seconds too late that it’s gone. But I believe the dream was necessary, it put things in perspective. I now realize that in life, I left a lot of people behind.

So, the dream – it started out with me finally being released from Death Row. I was given some clothes and a severance package, but when I got outside, no one was at the gate. No family. No friends. No news cameras covering the story. It was as though any relevance I had owned had succumbed to my absence, and the world had moved on without me. I headed home, but when I got there, it wasn’t the same house I remembered. The place was trashy and run-down with neglect, nothing left of the garden but wilted stems. The barn where we held so many of our family outings was now a crumbling derelict, trying to weather the times. All the holiday memories we made in that barn, and now it was no more than a safety hazard. Then I noticed a strange-looking structure. It looked like an igloo made of wood. And who do I see hobbling out from this dog house… yep. Bear – it was you.

You looked so mangy, worn-out and pitiful. Your eyes drooped with the age of years past. You looked like a dog that had been to hell and back with one foot still on the other side. The chain around your neck whined and creaked with the rust of twenty years. Your semblance, I hardly recognized. Then you looked at me and wagged your tail, and something in it spoke of you. I wouldn’t have guessed that any feeling could amount to walking off Death Row after twenty years, but seeing you was an unspeakable joy. And to think you’d waited for me all that time. The gratefulness brought me to my knees. You then bound into my arms with your incessant tongue laps and tail thrashing. No homecoming reception was ever more welcoming.

I was struck with the fact that you had been tethered on a chain for more than two decades. Blame set in on me like a scolding tongue for my leaving you to suffer so. Then I remembered… we never kept you on a chain. My eyes stung with the indecency. It seemed you were also unjustly serving time. I stormed off towards the house, ready to spit fire at the new tenants and demand the key to let my dog loose, but when I burst through the door, spraying glass shards and splinters, I unintentionally shattered the dream.

There is no ache like waking up to the longing of a friend who has never let me down. I kept trying to get back to sleep to rescue you and discovered that the most meaningful things in life are the most elusive. So, you see – it wasn’t a good dream at all, except for the joy of seeing you again. It made me realize what my sudden absence must’ve been like for you, how you must’ve felt abandoned by me.

Did you know the first time I saw you waiting inside the fence, I was reluctant and afraid. I was just dropped off by a parole officer, fresh out of prison that day. I wasn’t aware we even had a dog. I guess my fears stemmed from learning of the era when White supremacists set upon Black people with their dogs. I mistook your panting, pouncing, and acting so unafraid of me as a clear sign of your aggression. But then you settled down and let me pet you, and I realized that all you wanted to do was play. My first impression of you was so unfair. Maybe that is the real source of my guilt.

Needless to say, I was wrong about you, Bear. You just didn’t have it in you to hurt anyone. Well – there was that time when you snagged ahold the pants of that sheriff, but hell, you were only trying to get him off top of me. I remember thinking, ‘this crazy dog gonna get hisself killed’. Nobody had ever risked their life for me like that. I was so freaking proud of you.

I guess I should talk a little more about whatever since this will probably be the last time. It’s not really considered normal behavior for people to write to their deceased pets. I don’t mind coming off as weird; that’s just another word for unique, and sometimes it’s the most abnormal approach that is the only path to closure.

Often enough, there are times when I felt that you were the only one I could talk to, when I could do without anyone’s judgment or advice – I just needed somebody to listen. So many late nights I came home with my pockets heavy from all the dirt I’d done and my conscience weighing on my shoulders. I thought I had to wrong people to survive in the streets, when really I was just trying to be seen. My coming home to you was the only time when I felt normal. With you I could be my ugly self. I would unload all the day’s baggage at the doorstep while you lay curled at my feet, listening as my silent resolve. Bear – I can’t tell you how much having your ear meant to me. Hell, I’ve told you shit I ain’t told no one else. And on those rare nights when I didn’t drop by to unlatch your kennel and chat… well, on those nights my shame was a bit too heavy.

I’m sorry I couldn’t make it back to you, Bear, in both the dream and reality. I just didn’t know that my doing so much dirt would get other people’s dirt on me. I know you waited for me, and that must’ve sucked – wondering why all the late night walks around the neighborhood ended without reason, why all our fun just stopped. I want you to know that it wasn’t because I abandoned you, Bear – not intentionally. No. I didn’t come back because I, myself, am tethered by a red jumpsuit and Death Row has a really short reach. I keep on seeing that chain around your neck. I hope that wherever you are – somebody there will take it off. If not, I don’t know how the spirit world works, but I promise to take care of it when I get there.

So long, old friend, and thanks for all the times when your company gave me solace. There is no loyalty like a dog’s love. And, yep… I learned that from you.

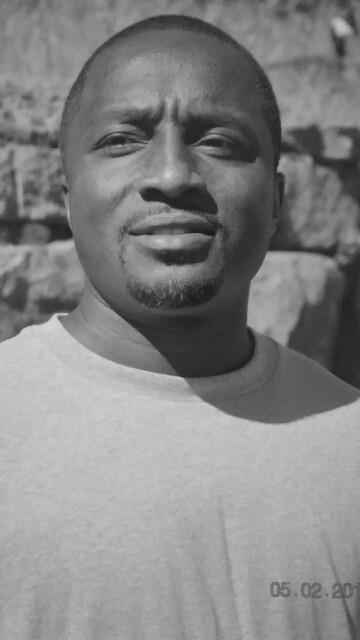

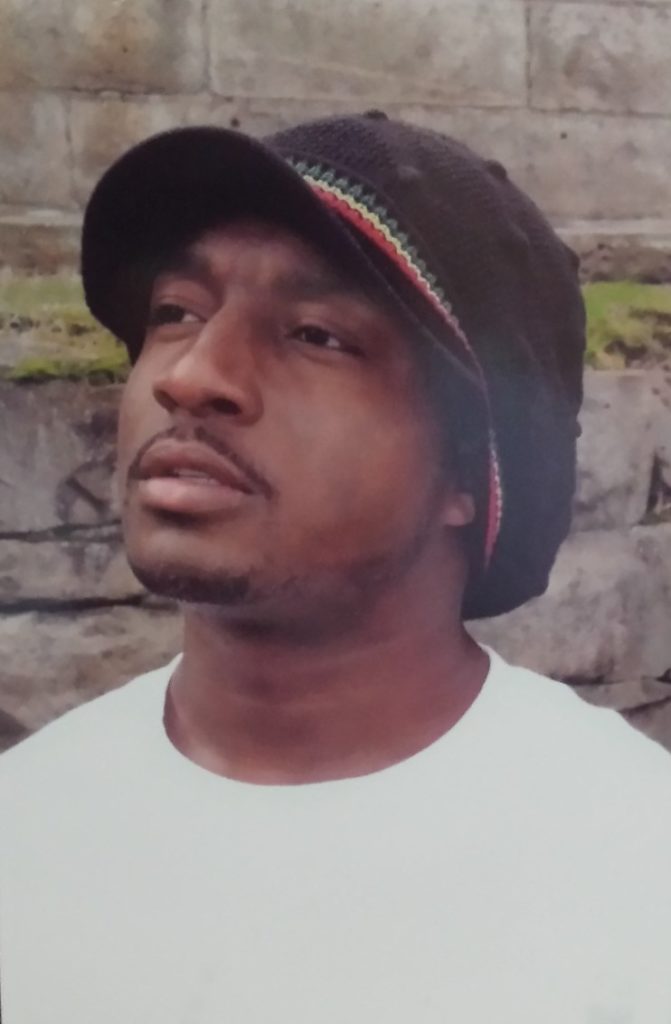

Always, your trusted friend and spirit brother,

Chanton

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: ‘Chanton’, is a member of the Board of Directors of WITS, and heads up a book club on NC’s Death Row.

He has always maintained his innocence, and WITS will continue to share his story and his case. On our Facebook page, we regularly share stories of wrongful convictions, they are real, frequent, and Terry has been living one for over two decades.

Terry continues to work on his memoirs, as well as a book of fiction, and he can be contacted at (Please Note, this is a change of address, as NC has revised the way those in prison receive mail):

Terry Robinson #0349019

Central Prison

P.O. Box 247

Phoenix, MD 21131

OR

textbehind.com

![]()