After walking away from a decade in solitary, I did not feel rehabilitated. I was and am frustrated at not really being able to understand the real damage done to my mind until I am released from prison all together. Who can predict the type of person or monster these isolation units will re-birth back into society? Is there a possibility that destructive behavior will be born out of being forced into an environment where an individual is purposely outcast, ‘misfitted’, and alienated through prolonged solitary confinement?

After walking away from a decade in solitary, I did not feel rehabilitated. I was and am frustrated at not really being able to understand the real damage done to my mind until I am released from prison all together. Who can predict the type of person or monster these isolation units will re-birth back into society? Is there a possibility that destructive behavior will be born out of being forced into an environment where an individual is purposely outcast, ‘misfitted’, and alienated through prolonged solitary confinement?

An elephant has one of the longest gestation periods, lasting twenty two months. A woman’s pregnancy lasts about forty weeks. The figurative gestation period of isolation units holding prisoners sometimes exceeds years, even decades. If the cells in a prison are the belly of the beast, the isolation units are the womb.

When prisoners are left to languish within isolation cells for prolonged periods, those cells then become a place of development. But nothing about this development period is constructive to the mind and spirit. The environment is made of cold metal and concrete and filled with air that carries the sound of screams, fists pounding on doors, and unpredictable moments of dead silence. There is little to no compassion or communication with the outside world, and the opening of the cell door acts as the umbilical cord the beast uses to maintain our life through food, mail and medications.

In the womb of a woman, a baby is surrounded by warmth and the nourishment of amniotic fluid. Doctors can test the fluids to determine the baby’s health. In the womb of the beast, there are no amniotic fluids, rather psychological pressure attacking those it holds within. The pressure is a mix of horror, anger, wrath, loneliness, hate and sadness. There is no way for doctors to test a prisoner’s well-being and monitor health. So what happens upon rebirth?

Some prisoners may come out strong, others broken, but all affected. Many will get lost in the psychological labyrinth and come out part human and part beast – psychopathic minotaurs.

Restrictive conditions within the ‘womb’, solitary, are radically different in harshness than in the ‘belly’, general population. When exposed to the radical prison gestation conditions of the Womb of The Beast, prisoners are more prone to develop mental and personality disorders, such as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, Post Incarcerated Syndrome, Dependent Personality Disorder, Bipolar Disorder, etc. While suffering such mental and emotional traumas, these prisoners are more susceptible to staying in or joining gangs, or worse, becoming radicalized for religious or political causes. All of which makes them more likely to commit more crimes upon release, even the extreme kinds. But, this could be the goal of the Beast and its many minions (investors and employees). If it doesn’t end, we will continue to see…

Illegitimate Trick Babies

Conceived from the blood of society’s lust,

Forcing thousands into an underworld

That never gave a fuck,

One way or another,

DNA make ups

Of crooked cops, prosecutors, and judges,

Who wear the masks of equality

Knowing damn well

They never loved us!

It’s Toxic Wombs Constructed

Of barbed-wire labyrinths of unforeseen change,

Too many years developing

Within the womb of a fiend,

Drowning us in the fathoms of tattoo tears

While constantly stabbing our souls

With infected syringes of loss and pain,

Depriving the many caterpillars

Held within its concrete cocoons,

Slowly killing the moths

Before they can reach

The lights of truth!

While Never Preparing

It’s offspring to breath

The polluted air of society:

“The Deceit of nature!”

Designed to systematically scrape you,

Of all your humanity

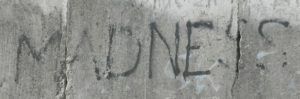

Sanity

And class,

While it proudly welcomes you:

“Com’on man!”

Before it’s billy-clubbed hands

Smack numbers on your ass,

Push you back inside

For the labor process

To start all over again.

WITHIN THE WOMB OF THE BEAST!

As you can gather at this point, I am not an educated person, nor a certified psychologist or behavioral scientist, but my experiences and my descriptions are truthful and authentic. My experience being exposed to solitary units for prolonged periods has afforded me valuable perspective. We need to continuously move toward abolishing the use of solitary confinement in all U.S. prisons.

While in general population, people often look at me strange when they realize I’m one of the guys who has spent ten or more years in solitary. Many have asked me, “Did you lose your mind while you were in there, bruh?”

I always reply, “Hell, nah. I’m too strong to go out like that!”

But the reality of it is, that I do not know how damaged I really am, because I suffer underneath my soldier’s mask of strength and fortitude and sometimes whisper to myself in the mirror, “They got me fucked up…”

But the reality of it is, that I do not know how damaged I really am, because I suffer underneath my soldier’s mask of strength and fortitude and sometimes whisper to myself in the mirror, “They got me fucked up…”

‘But, who isn’t messed up in some type of way?’ my thoughts try to rationalize with my deepest internal cries.

I am haunted by a statement made by Friedrich Nietzche in “Beyond Good and Evil” (1986):

“Whoever fights monsters should see to it that in the process he does not become a monster. And when you look long into an abyss, the abyss also looks into you.”

‘Damn!’

Leon Benson #995256

PCF

4490 W. Reformatory Road

Pendleton, IN 46064

(Due to mailroom restrictions, any communication with Leon Benson is required to be written or typed on notebook lined paper. Unfortunately, he cannot receive printed correspondence.)

![]()

When people try to tell me I can find a better ‘cause’ than criminal justice reform, it only punctuates how much need there is for education. This is just one story. This story and the countless like it are why this is my cause.

When people try to tell me I can find a better ‘cause’ than criminal justice reform, it only punctuates how much need there is for education. This is just one story. This story and the countless like it are why this is my cause.