In the free-world separating true worshippers from fake can be difficult. No doubt, some are true to what they believe, and for them, their faith defines their identity. In prison sorting the true worshippers from the fake is nearly impossible, many ‘in it’ only for what they can get in return. In here we have little variety, so the little variety offered, multiplies in significance.

Prison-issue anything is homogenous, monotonous, bland, devoid of personality. Even one’s personality can start to look prison-issued unless one actively strives to individuate – by getting sleeves of bad tattoos, for instance. Religious affiliation also offers a chance to stylize and spice it up a bit since each religion gives access to exclusive privileges.

If one registers as Jewish, he can receive a ‘special diet’ tray at meals, prepackaged Kosher food that’s fresh and edible, especially compared with typical prison-made grub, which is often congealed, stale, and wilted.

To prevent a choke hazard – think garrote – necklaces are prohibited. However, if registered as Catholic, one may place an order with a vendor for a fancy rosary. Nothing displays one’s piety (and class) like gold-fixtured, dried-blood-looking rosary beads made from compressed rose petals.

Muslims get access to Kuffs (knitted skullcaps) of various colors, and giving alms to the less-fortunate is obligatory. For some guys the deciding factor is the stylish cap that highlights their eyes. For the indigent, the guarantee of commissary items from their brethren is the appeal – plus they get a couple of annual feasts and can brag about (or sell) the lamb, fried chicken, hot sauce, and delicate flaky baklava they get to eat that we don’t.

Back in 2009, tobacco products were banned in state facilities, including prisons, but not for Native American practitioners, for whom tobacco is an essential element in praying. Overnight the Native population exploded from two people to thirty. Death Row’s population is only about 140. Each man lined up outside, stepped to the center of the sacred prayer circle, and the chaplain would hand him a medicine cup containing a teaspoon of pungent tobacco pressed into it’s bottom like a fat brown quarter. They could smoke it in their pipe, burn it in their smudge pot, sprinkle shreds of it into the wind – or secretly smuggle it back to their cellblock and sell it for a dollar per hand-rolled cigarette at least. They could easily get five bucks for that teaspoon – that’s 20 ramen soups or 25 coffee packets: that’s nine stamps or, for the druggies, five pills; or for the perverted, a blowjob from Randy. The Natives also get an annual feast they can brag about or sell food items from.

We can register with only one faith group at a time, but are permitted to change faiths every 3-4 months. That alone should tell you something about the waxing and waning of devotion in prison. Often, when one changes religions, his former faith’s paraphernalia – now contraband in his hands – finds its way to the black market. Headbands and Tupperware sacred-item boxes, prayer rugs, Kufis and Rasta caps, thick Bible dictionaries, prayer beads and shiny crucifixes. It’s all for sale.

Back when they banned tobacco, I registered as Native American so I could smoke and sell tobacco three days a week. I did this for years, despite being a professing Christian. Eventually, I felt so guilty that I left the prayer circle and re-registered as a Protestant. That first Sunday rolled around and I had no intention of attending church services with some I knew were hypocrites. Lying in bed, fiending for a cigarette, I heard a voice in my head that I attribute to God sounding like Charleton Heston in that old movie in which he played Moses. It was a deep, authoritative voice, with a slightly ironic tone. He said, “You went outside to smoke three times a week for an hour at a time for three years straight and missed not one day. In the rain. In the freeze. In the scorch. In the ants. You skipped weekly movies. You skipped recreation. You went through the strip searches… And you can’t go to church twice a week because of the hypocrites? So, there weren’t any hypocrites in the circle? Well, maybe not now, not since you quit going.” Of course I’m paraphrasing, not quoting verbatim, but you get the point.

I got out of bed and went to church. And I haven’t missed a day since, even after we Christians lost our three annual feasts we used to humble-brag about. I also no longer pass judgment on who’s real or who’s a hypocrite because I realize that despite being a sincere worshipper, I often do things to make this hard life a little softer, which from an outside perspective probably makes me look fake as hell. Even so, I am a Christian… meaning I’m forgiven, not flawless.

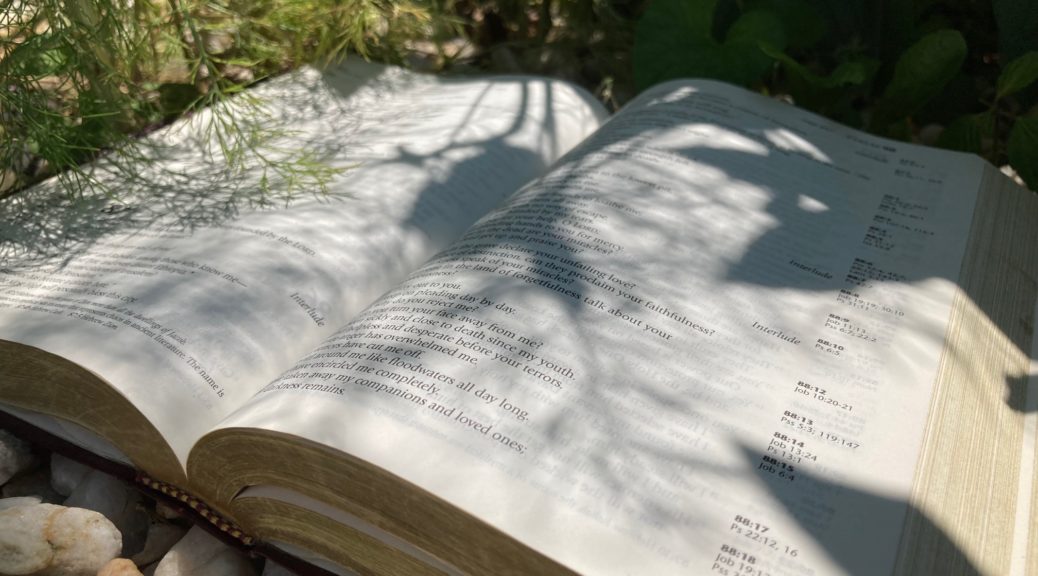

To demonstrate my devotion, I own the most expensive Bible in our small congregation, ornate, leather-bound, handmade (in China).

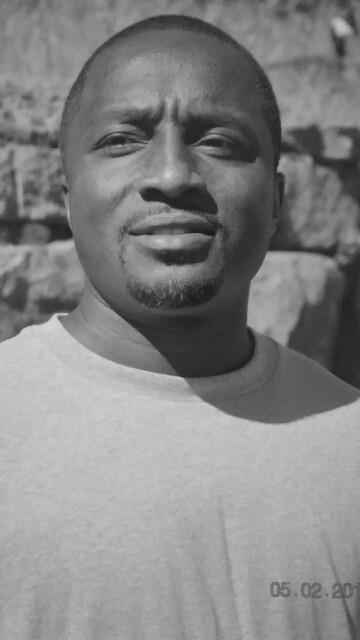

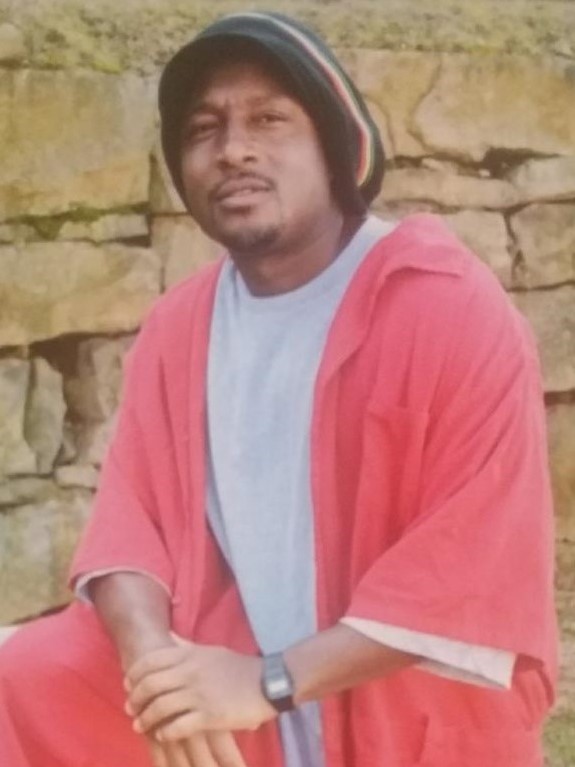

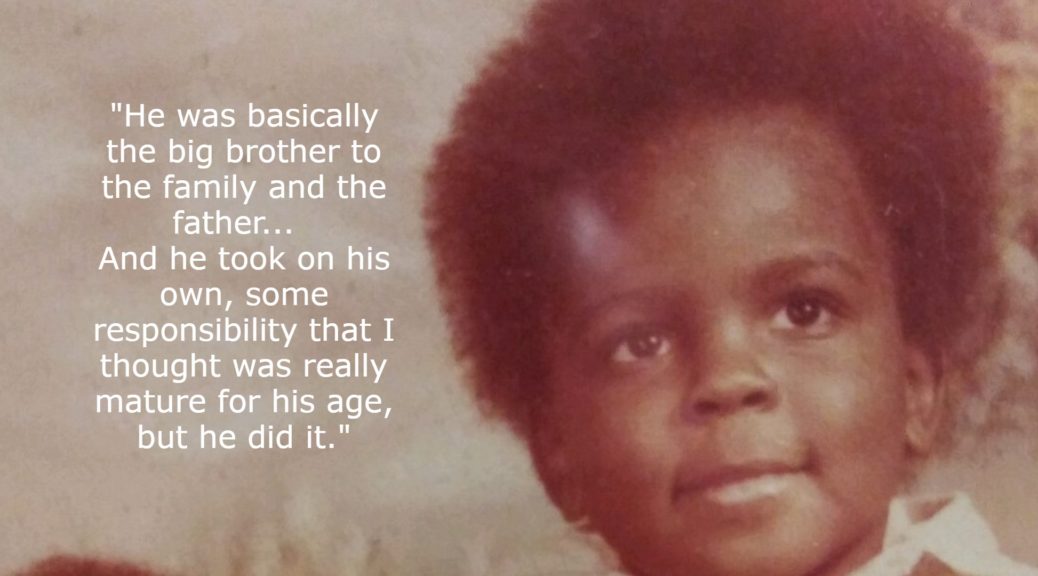

ABOUT THE AUTHOR. George Wilkerson lives on Death Row. He is a talented writer with a unique style, and a solid commitment to his craft. I know when I see a submission from George, I am going to enjoy the read, and I am going to share his work. He is consistent, he is original, he is thought-provoking. He is only an occasional contributor to WITS because he is working on his own book projects, and he is also a co-author of Crimson Letters. I am grateful he takes the time to share his voice here.

Mr. Wilkerson can be contacted at:

George T. Wilkerson #0900281

Central Prison

P.O. Box 247

Phoenix, MD 21131

He can also be contacted via textbehind.com

![]()