A lot has changed since I first arrived on Texas’ nefarious death row. I’ve met a lot of guys over the years, and many seem like decent men. They even gave me a nickname – Louisiana. The name was more about keeping the peace than seeking a new identity. Texas folks, inmates and officers, have a difficult time pronouncing my last name, which was irritating me ‘cause I assumed they were doing it out of ignorance and not because they couldn’t pronounce a name they had never heard before.

Some tried to say it like ’ma’am’ followed by ‘ooouuu’ or other variations. Then there was one redneck officer who called me ‘Moe-Moe’. I ignored him and wouldn’t answer. The convict population within Texas’ death row saw this would become a future altercation, so they simply agreed to call me Louisiana since that’s the state I was from. I settled with it.

I wasn’t the only guy with a nickname. Everyone seemed to have one. There was a Spanish guy named Casper (the ghost). There was a guy named Soultrain. There was a Youngblood and other names like, Freaky Frank, Oso Bear, Juke-box, Icy Red, Cash, B-Down, South Park, Third Ward, Sunshine (which he quickly changed to Youngsta), and on and on the list went. There was even a Ms. Good Pussy. And then there was Mookie.

I was still fighting off depression at the time, though I had become a little more optimistic. My mother had written me a powerful, religion-laced letter, and though I didn’t follow her instructions for praying to Mother Mary, Saint Peter, Saint Paul or any of the other Catholic saintly crew, I did however reread the line she wrote saying, “Talked to the lawyers today, and they told me in five years the system will correct the mistake they made and bring you back home…”

Five years? Granted, I didn’t want to hear that, at the time it seemed like a life sentence, but it did give me something to focus on. I mean, that was still 1,725 days away, but at least I had a benchmark to look to. That’s what I needed to keep hope alive.

I was allowed to go to group recreation which was a huge stress reliever. Just to be able to play basketball with other guys, bodies banging against other bodies, having locker room talk about ex-lovers. We were able to watch TV, Family Matters or ESPN, or play chess or dominoes at the tables back then. Camaraderie. I miss it.

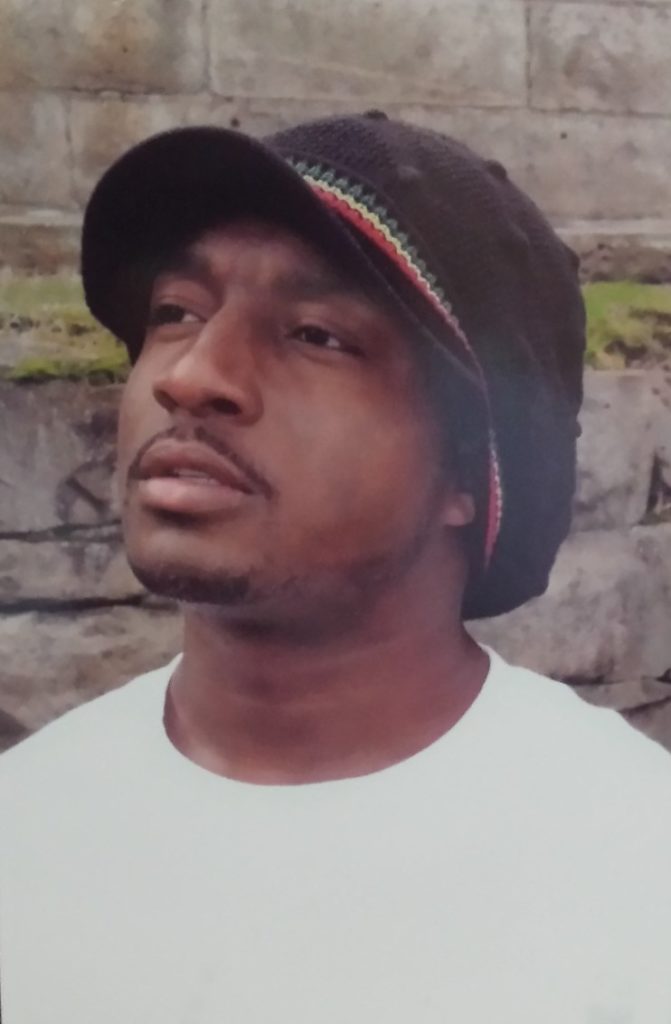

The first day I was allowed to join the others in group recreation, I was the last one to be escorted out. I immediately went through the process of matching guys with voices I had heard from my cell. Okay, that’s Casper. That’s J-Dubb. On and on it went. Guys came up to me and introduced themselves, but there was one guy that stood out. He was standing alone, arms folded, wrapped around himself. He was dark and handsome and stood a little over six foot tall. ‘That’s gotta be Mookie’, I thought. Everything I had assumed about him was wrong. I introduced myself, and our first meeting was very brief.

Days later I read about him in the newspaper. He had an upcoming execution date. Impregnated with the declaration my mother once made about my future, “Chucky will be a preacher one day,” I felt as if I was a shepherd and needed to tell my flock to follow me. I wrote Mookie a brief note, telling him to renounce his sin so he could enter the Kingdom of Heaven. You never know what kind of response you will get when you try to force your ideologies upon another, but I felt I had a duty to save this man’s soul.

He accepted my note, read it and told me he would get back with me later. Since his execution date was days away, he was allowed to spend commissary money on anything he wanted. He chose to buy everyone a pint of ice cream, which we all enjoyed and appreciated. Then he wrote me back, four pages, on yellow stationary. His handwriting was neat and artistic. He told me a parable.

The story was about a father and son. The son was asked to carry a pot full of water to a nearby town. What the boy didn’t know was that there was a hole in the pot, and by the time he arrived at his destination, all the water was lost. The boy was distraught, thinking he had let his father down, but his father told him not to blame himself. The two rewalked the path, and to the son’s amazement his father pointed out the beautiful flowers that grew along the side of the road where the water had been ‘wasted’.

Mookie went on to explain the story’s meaning. He taught me that I was in no position to judge any other, for I was not God. He taught me that every creation has its flaws, we all make mistakes. Some get public attention. Some don’t. Some people get caught. Some don’t. None of us are any better than the next. Mookie humbled me. He was executed/murdered days later.

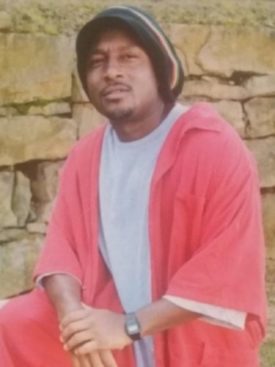

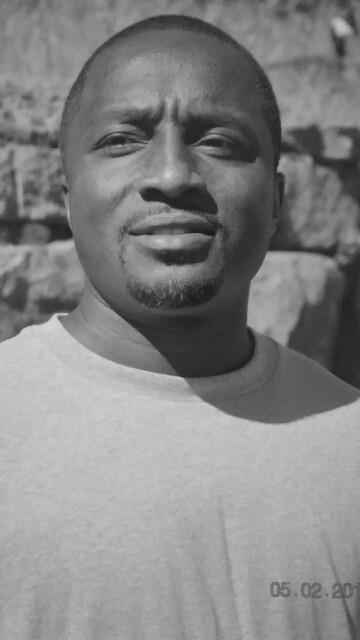

ABOUT THE AUTHOR. Charles “Chucky” Mamou is a long-time writer for WITS. He has also been the subject of WITS’ in depth look at how cases are sometimes mishandled.

Over the years, we have shared here how evidence was clearly kept from the defense in a death penalty case, information was manipulated and truth put on the back burner. For example, among a number of questionable actions taken in Mamou’s case, the prosecution was aware that physical evidence was collected from the victim and not only knew, but had the evidence processed. Mamou had no idea that physical evidence existed and exists – until it was recently located by an advocate. Yet, Charles Mamou is waiting to be executed and out of appeals. If you or I were to have knowledge of physical evidence and have it tested, not sharing that information with the opposing party, that would be an issue for the Courts. Why is this not an issue? You can read more about Mamou’s case and sign a letter requesting an investigation – please add your name to his petition.

Charles Mamou can be contacted at:

Charles Mamou #999333

Polunsky Unit 12-CD-53

3872 South FM 350

Livingston, TX 77351

![]()