For a time when I was a kid I dreamed of someday becoming an architect. While other kids reveled in stickball and tag, I opted for dirt schematics. The idea of designing and building homes was a playground for my mind. I’d sit in the Projects just waiting for rain, and when everyone else in the neighborhood stayed indoors to keep dry, my best friend Chris and I competed over the intricacies of our mud houses. I was fascinated by our ability to make use of the slush many others considered a social hindrance and mold it into a sanctuary. I carried that dream of being an architect for more than half my life, even when I was standing on the pathway to becoming something else. It was a dream that would survive adversity, unaffected by ill-fortune and one fostered by a purpose from God.

Today it’s injustice that has claimed my longtime dreams of architecture, and for the last twenty-six years I dream only of vindication. I’ve been in prison all this time accused of murdering a man named John by conspirators with motive and a trial court with terrible aim. Today I dream of accountability for those that wronged me and restoring my reputation. More than anything I dream the truth of my innocence will come out and I’ll be set free from Death Row.

However vindication can feel much like a pipe dream after over two decades of disappointment. Waking up day after day to being falsely imprisoned can render all hope lost. Yet I continue to dream of vindication in the face of disappointment out of necessity, needing to believe that my life does have value and a false accusation will not be my undoing. But whereas my dream of architecture was one of a soothing nature, the dream of vindication hurts. In one dream I felt fulfilled by future possibilities; in the other I loathe the coming days. Before, the dream was my inner refuge; today’s dream poses risk – the hefty toll of waiting around, hoping and praying for justice that may never come.

The fault was my own for dreaming so big when I knew damn well what I was up against. A man was dead and when someone has to pay, any old villain will do. From the moment I was accused and made a prime suspect, my innocence was in dire trouble. All I had to back me was the word of an alibi whose credibility was tainted by addiction. My downfall was the likeness of my two court appointed attorneys whose sole interest was in mitigation, a novice jury with no qualms of snatching away dreams, and a judge who orchestrated it all. The nerve of me to think I could ever be more than the model to which they assigned guilt. My innocence never stood a chance in a court of iniquities that operates on popular opinion. So here I am twenty-six years later, wrongfully convicted and trying to hold myself up with a dream, which seems so futile given the reality that my hopeful tomorrow will end much like my hellish yesterday.

Today, May 18, 2025, marked twenty-six years since I was falsely imprisoned for murder. Twenty-six years I’ve awaited vindication. Twenty-six years a dream has been deferred. Anyone who ever said “…don’t give up on your dreams,” ain’t never been to Death Row or they’d know the time spent on appeals is the real dream-killer while execution becomes the resolve. Twenty-six years and the only thing more damning than a dream that hasn’t happened is one that’s close but slipping away – when the supporters no longer rally, the faith dwindles, and the legal representation is slow to task. Twenty-six years and I’m back where I started, daydreaming of a life outside my prison cell while the passing time burns my vindication to ashes and leaves me to sift through the residue for a smidgen of hope that ‘someone somewhere’ will make things right.

I am innocent, and I won’t ever get tired of saying it. I’m not responsible for what happened to John. I was not a party in the commission of the robbery that killed him, nor was I privy to the criminal intent. I was condemned by fabricated testimony, misconduct, tunnel vision, and a jury eager to convict. But there’s someone out there that knows I’m innocent, as made evident by their account of the crime, that one person, the cornerstone of my vindication and who can attest to my innocence.

How am I supposed to fight a court system that re-envisions the facts and views circumstantial evidence as truth? Where is the victory if exoneration comes after they’ve stolen from me twenty-six years? Life on Death Row won’t sustain many dreams, but it will crush them under ominous heels. I’ll never become an architect… I know that now. My purpose is just to stay alive. Wrongful convictions are not a misfortune that falls on a few but a transgression that lands on many. My false imprisonment is a breach of moral ethics… it has to be because I’m innocent. So I’m appealing to all those out there who would dare to defy injustice – somebody somewhere please do something!

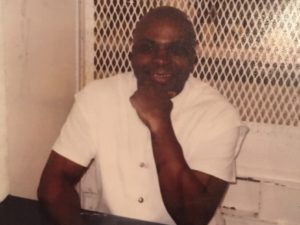

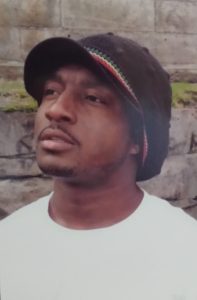

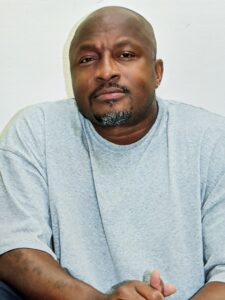

ABOUT THE WRITER. Terry Robinson is a long-time WITS writer who writes under the pen name Chanton. He is a member of the Board of Directors of WITS, and also facilitates a book club on NC’s Death Row. He has spoken to a Social Work class at VCU regarding the power of writing in self-care, as well as numerous other schools on a variety of topics, including being innocent and in prison.

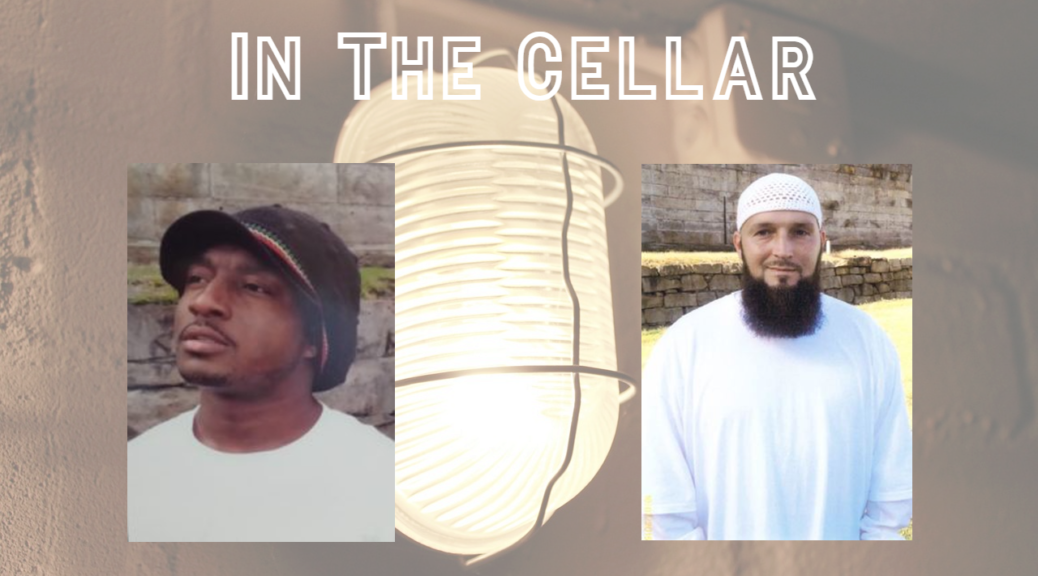

Terry Robinson’s accomplishments are too numerous to fully list here, but he is currently working on multiple writing projects, contributes to the community he lives in including facilitating Spanish and writing groups, and is co-author of Beneath Our Numbers: A Collaborative Memoir From Inside Mass Incarceration and also Inside: Voices from Death Row. Terry was published by JSTOR, with his essay The Turnaround, he was a subject of an article by Waverly McIver regarding parenting from death row, Dads of Death Row, and all of his WITS writing can be found here. In addition, Terry can also be heard here, on Prison Pod Productions and also as co-host of In the Cellar, a podcast that explores the challenges, tragedies and triumphs of living with a death sentence.

Terry has always maintained his innocence, and is serving a sentence of death for a crime he knew nothing about. WITS is very hopeful Terry Robinson’s innocence will be proven, and we look forward to working side-by-side with him.

Terry can be contacted at:

Terry Robinson #0349019

Central Prison

P.O. Box 247

Phoenix, MD 21131

OR

textbehind.com

His writing can also be followed on Facebook and any messages left there will be forwarded to him.

![]()