It’s the look in his eyes as he spits some slick disrespect in my face, not bothering to stop at my cell, casually flaunting his freedom. It shouldn’t come as a surprise to me. It was such seemingly casual violence on my part that saw me into a cage after all.

But the sting of helplessness, of a raw, exposed nerve, the vulnerability, leaves a metallic, blood-like taste in my mouth, slashes at my soul… It’s a feeling I quickly cover with splashes of rage, the most potent form of emotion I can find. Funny that it lives next door to passion and across from love in me.

It’s a child’s reaction to the inability to deal with a moral responsibility seeking to overwhelm me, to rise in me until it covers my nose and I can’t breath for the insanity in my mind… a refuge denied to a man with a gun in his face.

The greater the fear, the thicker the lid of the angry outburst needs to be to hold it down, the fear of being at another’s mercy, subject to their whims, their madness.

This is what people felt when a kid stuck a gun in their faces and took their money, their freedom, boldly stomping through their lives as if they didn’t matter. Was my stride the same as George Zimmerman’s, the officers’, the guards’? Did I have the same ‘fuck you’ strut and that same look in my eyes?

“It ain’t no fun when the rabbit’s got the gun.”

I fall back on my bunk, into the prison of my life, swallowing the taste in my mouth. Life is about the connections you make, if and when you are able to put the pieces together. An I.Q. test measures how quickly a person can pick up a concept, make a connection, spot a pattern. Is there a test to show whether someone cares enough to make the attempt? That info seems more valuable to me somehow.

This isn’t who or where I wanted to be, living within circles within circles of violence, violence with no goal of shaping me into the dreams of my grandmother, my father.

Change. That’s what’s left after trans-for-mation. No matter what I change, or who or what I forge myself into, the things that truly confine my life will not budge. They’re built to outlast me. Despair? No, reality.

Hear me. Most people live in a world of ‘potential’. Some one(s) planned on me being in this cage more than eighty years before I was born. How do I change that? How did they know that I would shoot that white man? That my seventeen year old black face wouldn’t be remembered by him in either rage or fear?

In the face of such forgiveness, how could I fail to forgive the guard? His ignorance hadn’t left me with a bullet in my spine, unable to walk or live without pain. I couldn’t say the same for my own.

Moral culpability is the substance that adulthood is made of, the mortar that binds the actions of our lives together like so many river stones. But the energy of such a powerful emotion – rage – doesn’t simply evaporate under the heat of responsibility. It was only then, after I pulled that trigger, that I recognized the extreme danger – Quicksand!

This is where brown boys who are guilty get reduced to numbers in boxes, like lotto balls, to consume what is left of themselves. It happens in secret – a private meal washed down with a grandmother’s tears, as the child she loves crumbles under the weight of a basketball score in years.

That’s all that was left after I sacrificed my childhood’s hopes with the blast that shattered multiple lives, only to rise like smoke on the winds of reason. I couldn’t to this day tell you why I pulled the trigger. Reason will ever be the enemy of children.

It’s what was left after the white D.A. and my white attorney saw a seventeen-year-old brown boy agree to plead guilty and to ninety years in prison.

It’s what was left after the white judge refused to find anything redeemable in my childish eyes. I was guilty, nothing more.

What is left is twisted into this callous on my soul. Armor. A thickening of the skin, instinctively grown to protect the child in me from what I’d done – what was being done to me. An act that none of the only white faces, save my three people, in the courtroom seemed to look interested in, watching the judge hand down a ninety year sentence for a non-homicide offense to the brown kid that I was.

Should race have excused or defended me? Never. But when the lines of brown boys waiting to be sent to prison by predominantly angry white judges stretches into the horizon… and has done for decades…

If you are looking for the stereotypical black rage found in the ink of most prison pens that allows one to dismiss the words as broken, to look away from the destruction by fire of brown skinned boys measured not by the love and mercy due a child at their worst but in metric tons – this is not that.

To not look away is to see, to see is to know, and to know as an adult makes us morally culpable to act. Adults should expect the morals of their justice system to reflect their own values. It’s the only way the American system works.

There are white people standing with the black lives movement, armed with their own rage at what they have seen and know to be deadly and murderously wrong with what is being reflected back from our justice system. “What are they doing out there?” is what some ask. What should be asked now that they’ve seen and know is, “What am I doing in here?”

It’s what I ask myself every day.

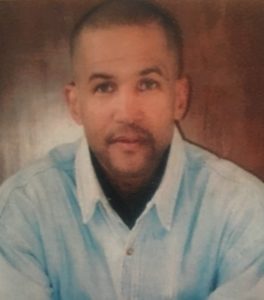

ABOUT THE WRITER. Mr. Jones is one of the newest writers in this family. His writing is brutally honest, and although being vulnerable might not be comfortable, he goes there every time with his writing – setting him apart. I don’t think he could write anything I wouldn’t like.

Mr. Jones has served 32 years for a crime he committed when he was seventeen years old. He can be contacted at:

DeLaine Jones #7623482

82911 Beach Access Road

Umatilla, OR 97882

![]()

A week before Christmas, 2013, one of my female students lost her fifteen year old brother to suicide. He had been bullied through elementary and middle school and decided he didn’t want to live anymore. My student, along with her family, found him dead in his bed – no note, no explanation. Just gone.

A week before Christmas, 2013, one of my female students lost her fifteen year old brother to suicide. He had been bullied through elementary and middle school and decided he didn’t want to live anymore. My student, along with her family, found him dead in his bed – no note, no explanation. Just gone. Days turned into weeks – weeks turned into months. Finally, the day came when he asked me, “Darrell, do you think that I can write good enough to send my dad a letter?” Without saying a word I slid him a blank piece of paper and handed him a pen. As I sat and watched, he painstakingly printed on the paper…

Days turned into weeks – weeks turned into months. Finally, the day came when he asked me, “Darrell, do you think that I can write good enough to send my dad a letter?” Without saying a word I slid him a blank piece of paper and handed him a pen. As I sat and watched, he painstakingly printed on the paper…