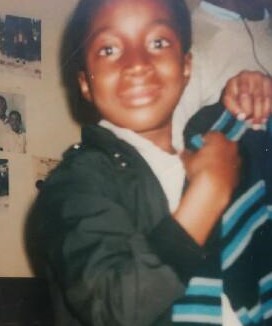

Felicia was a ‘round-the-way girl, someone everyone knew. She was constantly on the go and always in the mix of making moves that were typically illegitimate. The younger sister of a local tough who was known for his street brawling during the 80’s, Felecia did not command the ruggedness and knack for violence her brother had. Instead, she was an enigmatic young woman, rather timid and reserved, with striking natural beauty.

I first met her in September ’97 after my release from prison, where I was introduced to radical concepts about Blacks and Whites, many of which I refuted. Still, I was inspired by the talk of Black Empowerment. At that time, I needed to believe in something, but having spent 31 months wrongfully convicted, I was too bitter for decent living.

Felicia came through the block, headed toward the school yard, her steps seasoned with haste. She was on her way to cop some dope. Felicia was addicted to crack cocaine, still in the early stages from the looks of her. Clean fingernails. Stylish hair. Yet her name had reached the lips of every hoodlum with the lowdown as they wove her sordid reputation.

Rejection is a common occurrence ‘round-the-way. Everything from character flaws to unpopular choices may result in one being devalued and mistreated. Felicia was different. She was salvageable and brimming with potential. Why no one seemed to be trying to help her, I couldn’t figure. Surely she had a family somewhere with tear-soaked pillows and calloused knees who prayed for her sobriety. To the dealers and other addicts though, Felicia was a lost cause, good only for her prettiness to squelch their own insecurities and quench their broken desires. Well, not me. I resolved to make a difference in her life. The only problem was, I, too, was broken.

The more prominent I became in the dope game, the more I saw Felicia, zipping here and there while on a mission. Her taught lips in a forever smile were the mark of someone special. Here eyes sparkled with hope. I spoke to her often, expecting to be ignored, though I found that she reciprocated. I challenged her choices and she revealed to me the letdowns that had driven her to dark places. Erroneously, I gave her some crack cocaine because I wanted to help. I vowed never to accept her money. But was I really helping Felicia, or was I quieting my own conscience?

As the weeks and months wore on Felicia, she looked tawdry and unclean. The sparkling hue in her eyes extinguished by an unrelenting pain. She held up in abandoned corners too dark for shadows and took refuge in a glass stem while the johns sought after her day and night, devouring what dignity she had left.

After my joy of being out of prison ran its course, all that remained for me was resentment. Consumed by the feeling of self-worthlessnes, I mirrored how I felt. I woke up angry, dressed in vengefulness and headed out in the world to detonate. I dismissed Felicia’s sickness and potential for hope, and I accepted her money for drugs.

One night I was cooped up in my apartment alone, when someone rapped on the door. It was Felicia, glancing over her shoulders with her eyes weary and strained. She jabbed at her ponytail with one finger, scratching away at her scalp as she clutched onto a fistful of bills and said, “Lemme git a dime.”

I took a twenty-dollar piece of crack rock, split it in two and dropped half in her hand.

I’ve got eight dollars,” she revealed after handing over the money and eyeballing her purchase.

Expecting the funds to be short, I didn’t bother to fuss. I put the money away and closed the screen door, but Felicia didn’t leave. She stood there and plopped the crack rock in her moth, taste-testing the product. “You got something bigger?” she asked.

“What! Man, go on somewhere, Felicia,” I chided, frustrated with her antics. “I’ve already given you more than what you paid.”

“I know, but that’s my last eight dollars. You can’t gimme another piece?”

I refused. She persisted. Suddenly, we argued, the tension growing with every second.

“Just gimme back my money,” she demanded. “If not, I’ll call the police.”

I should’ve just given her the money and cut ties. What was only eight dollars to me – was worth so much more to her. Yet, I was insulted and spurred by anger. I hocked saliva and spat in her face. “Bitch! Git the fuck off my porch before I come out there and beat yo ass!”

Gone was her moment’s sense of defiance, replaced by hurt and shame. She looked on me until I looked within myself, and all I saw was guilt. Unable to bear the sight of my depravity, I slammed the door shut while peering out the window as she wiped away the froth and vanished.

I sat at the kitchen table in the dark of night in the company of self-reproach, wondering how much Felicia suffered at the disdain of heartless men. Men like myself who objectified women and perpetuated machoism, men who willfully victimized the weak and defenseless. A man who would spit in a woman’s face and hide behind the door – though I couldn’t hide from my own disgrace, and I am still ashamed today.

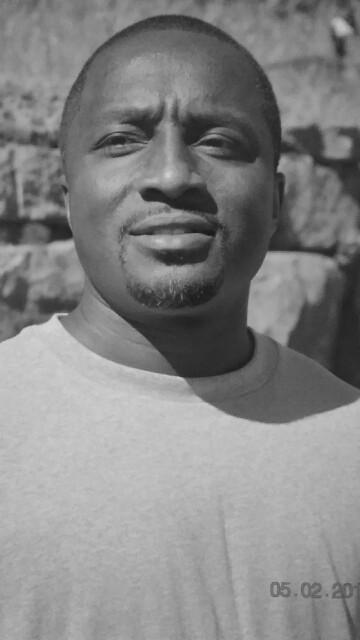

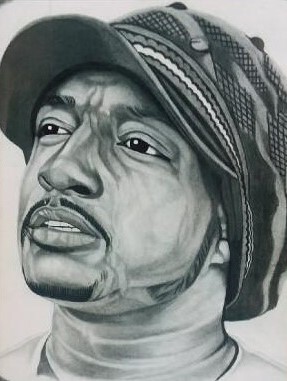

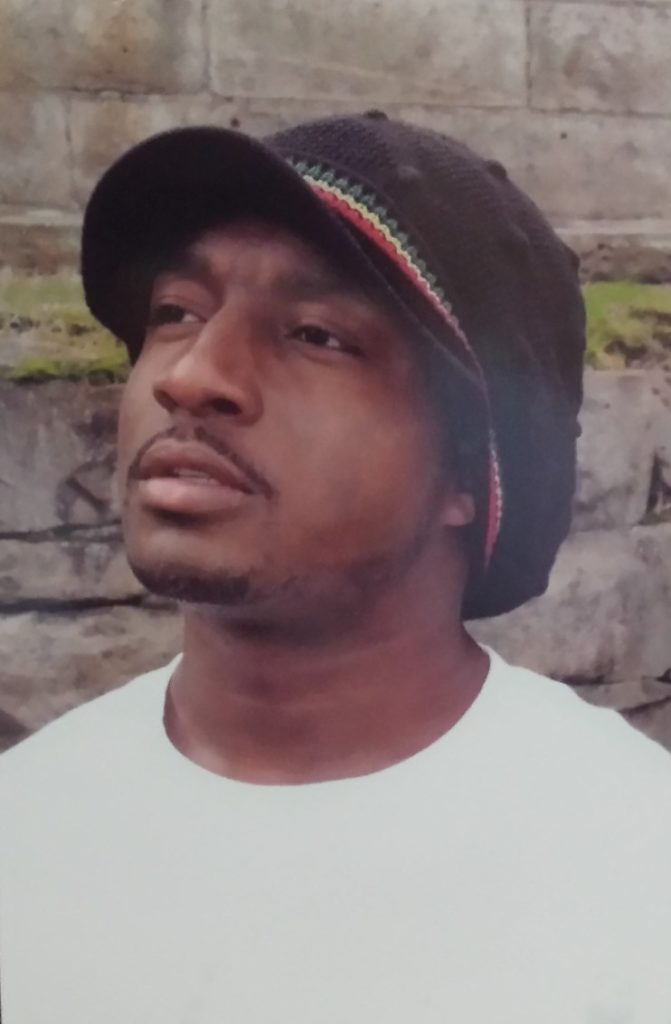

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Terry Robinson writes under the pen name ‘Chanton’, and this year he has seen the release of Crimson Letters, Voices From Death Row, in which he was a contributor. He continues to work on his memoirs, as well as a book of fiction. Terry Robinson has always maintained his innocence, and hopes to one day prove that and walk free. Mr. Robinson can be contacted at:

Terry Robinson #0349019

Central Prison

4285 Mail Service Center

Raleigh, NC 27699-4285

![]()