I spent years not knowing who I was on the inside, a state that is its own form of prison. From age fifteen on, I felt insecure about my past, the crime that brought me to prison, the lack of having ever actually done anything in my young life of meaning or enjoyment, and even about not fitting the ideal of what a ‘real’ prisoner should look like. I did all I could to mask those feelings, put on a front and hold myself together in prison.

I spent my first few years of incarceration in a prison for Youthful Offenders. There was plenty of violence there, and knowing I would later be going to an adult prison until I was forty, I decided to put on some size. I worked out like crazy to make up for the fact that I couldn’t make a convincing ‘mean’ face if my life depended on it. I tried to compensate with the amount of weight I could throw around, which was considerable until I injured myself so badly I couldn’t do a pushup for a couple years. I learned the habits of hypermasculine men, things like eating a banana by breaking it into pieces first so no one could sexualize it. I learned how to talk to others, and in some ways I found part of the person I could have been if I had not destined my future to incarceration.

Getting locked up before I came into my own, I had a bad habit – among others – of trying hard to fit in with all groups and all people, trying to find what we had in common and how we were alike. I’d talk about money with bank robbers, drugs with addicts, smuggling with cartel members… I’d discuss God during the years I was agnostic, leave behind a conversation over a television show with a supremacist to talk politics with a member of the Nation of Islam. Looking back, I recognize that some of that was because I was just interested in other people and their perceptions, having come from an isolated background. But some of it was because I didn’t want to be the odd man out, and some because I feared being alone in a very hostile and dangerous environment. Guys who didn’t fit in didn’t tend to have a lot of friends, and guys who were too different were targeted. I was already of small stature, childish features, and I wore glasses. I had twenty-five years to do, and I didn’t want that to be how my life was defined on the inside.

After enough time locked up, even a kid from the suburbs can talk gangster, and I could even pass, in short spurts, as ‘hood. I hadn’t done many drugs on the outside, but experienced a fair share after getting locked up, and growing up around the people I did, I knew more about guns than most people locked up for shooting someone. Those things and women are the things discussed most in prison.

I was smart enough and read a lot, so I knew at least a little about most things. This got me a job tutoring in the prison GED school when I was still too young to have graduated high school. Teaching and helping others from all walks of life helped me to relate to others, and my time in prison was easier for a while. Some Bloods stood up for me, some Crips tried to recruit me, some Skinheads liked me, some Latin Kings had my back, and some members of other religions tried to convert me, though I never chose to join any of them. I could get along with just about anyone, but who was I really? Did any of them know the real version of me? Did I even know me for sure?

It’s hard to quite know who you are when your own history is something you’d prefer to escape, and your present is… well, also something you’d prefer to escape. It’s like being lost in the woods at dusk with no way to find your way backwards and the vague understanding that you likely have a thousand miles to go. You’re left only to push forward, survive the journey, and along the way, search for the soul that crashed like a meteorite in the wilderness years ago.

I spent my first few years learning to survive without the future in sight. My high school class graduated while I was locked up, and the few friends who had written moved on as we grew apart and they went on to college. Smartphones connected everyone, loved ones passed away, guys I knew on the inside were released and came back, and all the while I stayed in one place. I lived in the moment a lot, getting lost in them and the days and years, lost in stories told by those around me of their lives and dramas. I remember the names of girlfriends of my first five cellmates, and I remember the prison-friends I made as a teenager much better than almost anyone I’ve known in the fourteen years since. It was like high school in some ways, those early memories seeming a big deal and sticking with you because they were a part of your formation as an autonomous individual. Those who were there were part of the concrete of your identity during the final churning in the mixer.

I felt most insecure in the experiences I knew nothing about, never living on my own, never having a driver’s license. I never had a serious girlfriend, never went off to school or moved around, or saw much of anything except some childhood trips around the country. I didn’t know how to cook or eat healthy, didn’t know how to pay taxes. The few wild stories I had took place in prison. Listening to others around me, I couldn’t relate, nor could they relate to me unless I avoided the subjects completely, so I asked questions and listened a lot.

What began as defense mechanisms turned out to help me as I was fortunate enough to meet a handful of new friends on the outside, usually through my dad. I could not meet anyone without that person making the choice to open up to me, and when they chose to, they found someone who was genuinely interested in everything they had to say. I gained understanding of life that way, of the things normal people deal with on a day-to-day basis. These friends helped me remain human, rather than turn into a toxic caveman.

Within prison, I discovered people often actually liked me as a person. Sometimes I found myself, especially in my early twenties, trying to act cool, or what I thought was how someone who was cool would act, and made a fool of myself more than once. I went through a period when I used a fair amount of substances to deal with depression and the chronic anxiety that came from feeling I’d wasted my entire life. That feeling defined me for a couple years, because it was so true in many ways. I committed an adult crime with a child’s mind, I harmed people I loved and created the whirlwind I fell into. At times I did not know who I was, but whoever I was, that was all a part of me. It was my life, and there was no running from it.

I was a loser. Not to be self-deprecating, but I was, because I sure hadn’t acted like a winner. But even in prison things grow, whether they be noxious weeds or better things. I decided I didn’t want to be like that my entire life, and though I struggled through the years, bored and occasionally terrified with a few moments of wonder, I managed to grow myself. I became quite an amazing cook as part of an introductory culinary arts vocational class, and later became a tutor/chef. I learned enough about law to help a teen get out of prison. I started writing, creating, drawing and constantly reading. Eventually, I learned about so many things I would have had an interest in had I not been locked up. I learned about what I wanted, began to see what I had the ability to create instead of the destructive tendencies that brought me to prison. I made friends, and I started having more experiences and more to talk about. I trained dogs, wrote for books, and performed with bands in prison concerts.

Though I still preferred to listen, I started to discover who I was, to find myself in the shadows despite being behind bars for the majority of my life. I still can’t make a mean face even if it meant my early parole, but I don’t really care. I still get stares from the predators when I eat a banana the regular way, but my beard makes me less appetizing and at 33 they know not to mess with me. I know how to get along with everyone, but I’m much more discerning about who I choose to talk to. The biggest thing that has changed about me in here is getting rid of my ego, which took work, and giving up on trying to fit in. When I did, I found that more people took to me than ever before. Maybe that’s what becoming an adult is, as opposed to a child. I grew up, and I did it in prison. It’s possible to find out who you are behind bars… but it can be a bit harder.

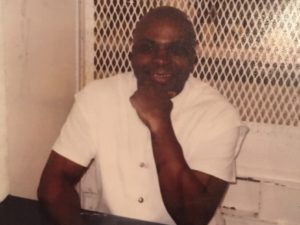

ABOUT THE WRITER. This is Chris’ first time writing for WITS, but he has been writing for some time. He wanted to share his perspective on what it is like to grow up in prison. If you would like to contact Chris, you can do so at:

Christopher Dankovich #595904

Thumb Correctional Facility

3225 John Conley Drive

Lapeer, MI 48446

![]()