It was an early Saturday morning along our town’s main street, a brisk chill in the air carrying discordant chatter. Revelers gathered shoulder to shoulder in heavy jackets and mittens, braving the joyous winter air of Christmas. Popcorns, candies, grilled franks, and 10¢ soda in paper cups pleased tongues and tummies alike, and hearty smiles reflected on the faces of people from all walks of life, differences put aside for another day. Utility trucks crept along at a snail’s pace, bearing floats decorated with scenes of the Nativity, and community volunteers put their talents on display, from dance troops to horseback riders. Everyone had come out for the arrival of Santa, but my anticipation lay elsewhere.

I was nine and hardly interested in the frills and cotton generated snow that day. It was the first time I was going to see my big cousin in a parade, marching in the high school band, a moment sure to put our family on the map. Before then, there hadn’t been anything noteworthy about our family, nothing in the history books to mark our plight.

We were the typical fishing trips, backyard cookouts, and holiday get-together family, with the occasional in-house drama kept to a whisper. But that day, I felt like we were a noble clan in a swell of common folks giving praise to the man of the hour in his bloated red suit, while we celebrated the achievement of one of our own.

Santa cruised by in a decked out jeep loaded with knapsacks marked ‘Salvation Army’; the star attraction, he was, with his cherry stained cheeks and grin that promised to fulfill Christmas wishes. Workshop elves and other parade hopefuls poured through in the unfortunate shadow left by Santa’s star power. Then it came, the thundering percussion and blaring notes stretched gloriously around the corner – the Beddingfield marching band was on the move.

I craned my neck and stood tiptoed, but the crowd was thick and blinding. Taking the steps three at a time, I found the greatest shoulders on which to stand to be the top landing of the Superior Court building. From on high, I watched the drum major appear with his juking dance moves, the middle of the street his stage. He was flanked by darling majorettes in spandex and twirling batons, and behind them came the marching band in their swanky blue uniforms and bedazzling gloves glinting golden in the morning sun. They swayed with synchronicity, the woodwinds flittering their fingers while the brass raised their horns to the sky in devotion. Lastly were the percussionists, their booming sounds causing windows to shudder as the sidewalks threatened to crumble under dancing foot soles. I recognized the confidence of one drummer as his wooden sticks rapped on with fluidity, passion, and wonder; it was my big cousin – the drummer boy.

A lover of music for as long as I can remember, Big Cuz fostered an inner relationship with beats that ran deeper than any 3-minute song track. Everything from pencils, pens, and twigs transformed to drumsticks in his hands as he conjured up sounds that were funky and raw. I was there when he was gifted his first drum set on Christmas morning when I was five, and he woke me up early to watch him play. He was a one-man band, convinced that he would someday make a living off the drum beating in his head. He sat me down at his station that day and taught me a 4-count combination, one that would evolve into my own fondness for the craft. And now, there he was, drumming in the Christmas parade with a flare that riveted the crowd and a spirit that stole the show.

The marching band fanned out for a halting performance as I waved exuberantly from my courthouse perch. Big Cuz drummed like it was nobody’s business, except ours… his song was an anthem of our family. He beat his drums with a fierceness that was nothing short of a statement to the world that said he had finally arrived. The band commenced playing medleys of current hit songs until the exhilaration in the crowd was spent, then the drum major carried on with his marching cadence, grooving on down the street with majorettes and marching band in tow. I watched as Big Cuz faded from view with his sound so distinguishable that everything else was background noise. His was an extraordinary talent that nestled in the hearts of listeners. Soon the parade was over, the streets swept clean as the crowds returned to life as normal…

Normal until 17 years later. This time, the spectacle would play out inside the courthouse. There would be no drum major that day, only a judge with a strict reputation and a lone majorette to his right, wearing a tweed jacket and plucking keys on a stenograph. The band included the raging prosecutor, spewing accusations on the woodwinds, and the sub par defense attorneys blowing smoke on the brass. And the crowd, twelve faithfuls hand-picked from the jury pool, their perspectives would scream the loudest. I was the star attraction this time, sitting at the defense table, charged with 1st degree murder. The stage was set. One by one the witnesses paraded before the jury, a prelude to the main event as the door opened behind the judge’s bench and in walked the State’s star witness – the drummer boy.

Big Cuz must’ve shed his confidence somewhere, along with his uniform, because he spent much of his walk looking down trying to find it. His eyes swung low like pendulums with a razor’s edge, ready to slice my character to pieces. He climbed the steps to the witness stand where he could see me from up high, his passion now gone, replaced by desperation. He then placed his hand on the Bible, this wooden stick stained and hollow, as he swore to play a song of truth.

I then listened as Big Cuz wove a tale of robbery, murder, and confession, drumming up lie after lie to the amusement of the jury. They rewarded him with their steadfast concentration, it was a sound they hadn’t heard before. The questions poured in from the prosecutor who proved masterful at conducting testimony, while my brass tongue attorneys sowed woeful discord with their blaring objections. The encore fell to the prosecutor when he asked Big Cuz, “Is the defendant there the man who told you he killed someone?”

“Yes”

“And who is he to you?”

“My cousin. Terry Robinson.”

With that, Big Cuz drummed his final note and scurried out the door, his beats reverberating throughout the courtroom long after he was gone. The jury found him credible and applauded him with their guilty votes; it didn’t matter that I was innocent, to them I was background noise. Once again, I was impacted by the drummer boy’s performance, except this time in the very worst way, costing me more than a biting chill, 10¢ sodas and spent legs laboring up the courthouse steps – this time it cost me my life.

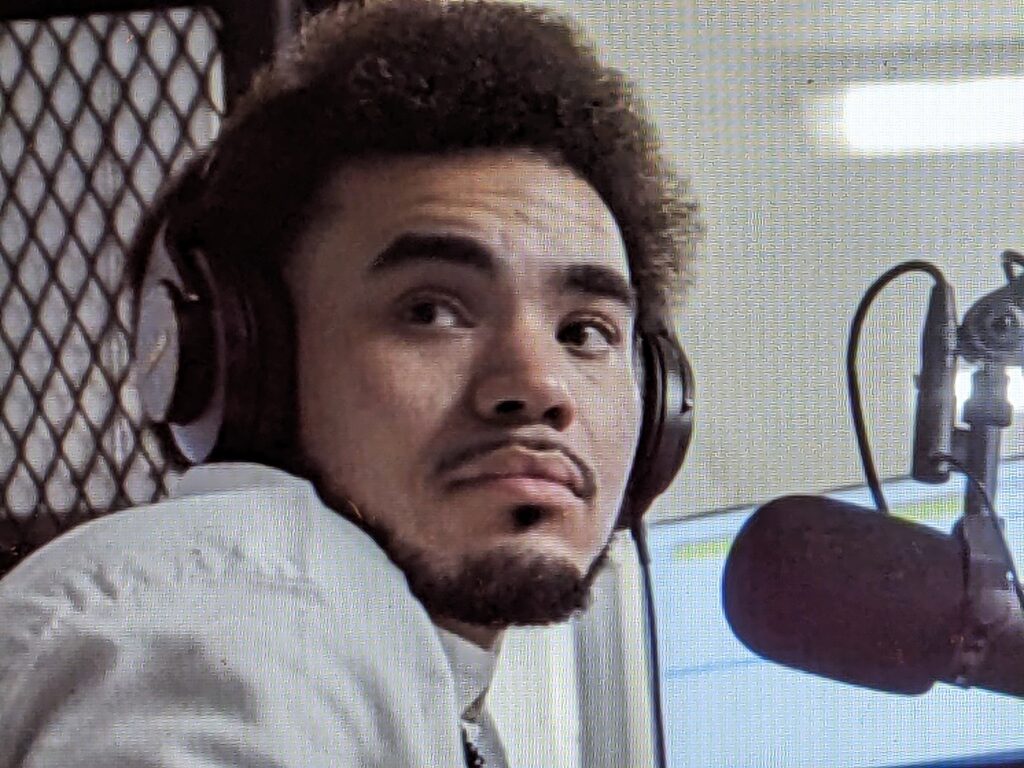

ABOUT THE WRITER. Terry Robinson is a long-time WITS writer who writes under the pen name Chanton. He is a member of the Board of Directors of WITS, and also facilitates a book club on NC’s Death Row. He has spoken to a Social Work class at VCU regarding the power of writing in self-care, as well as numerous other schools on a variety of topics, including being innocent and in prison.

Terry Robinson’s accomplishments are too numerous to fully list here, but he is currently working on multiple writing projects, contributes to the community he lives in including facilitating Spanish and writing groups, and is co-author of Beneath Our Numbers: A Collaborative Memoir From Inside Mass Incarceration and also Inside: Voices from Death Row. Terry was published by JSTOR, with his essay The Turnaround, and all of his WITS writing can be found here. In addition, Terry can also be heard here, on Prison Pod Productions.

Terry has always maintained his innocence, and is serving a sentence of death for a crime he knew nothing about. WITS is very hopeful Terry Robinson’s innocence will be proven, and we look forward to working side-by-side with him.

Terry can be contacted at:

Terry Robinson #0349019

Central Prison

P.O. Box 247

Phoenix, MD 21131

OR

textbehind.com

His writing can also be followed on Facebook and any messages left there will be forwarded to him.

![]()