I was about fifteen years old when we moved into a yellow, three-story country home in an upper-middle-class community in Georgia. It was a new house in the type of neighborhood where good southern people waved as they drove or walked past. Lots of teenagers lived in the neighborhood, and there were times when it didn’t matter that I was the only black kid around… and then there were times when it did.

My mom had been married for a few years by then. The success of her and my stepfather’s careers as computer engineers was beginning to show. They drove nice cars and wore business suits to work. They spoke the speech of the successful, not the patois of the impoverished black communities that spawned them, and our new home was the first sign that my parents were living the Black-American dream.

I was living the Black-American dream, too, for the most part. I loved that house. It had a wraparound porch with an old-style swing, a basement, and a two-car garage. The front and back yards seemed endless. Across the street lay a pond where people sat in lawn chairs, with fishing lines slung into the water when the sky was blue and the clouds were few. Some nights I swung on the porch watching the sun set over the shimmering pond, a whisper of wind chimes clanking on the peaceful breeze from a far off house serenading me.

It was the early nineties, the golden age of the Super Nintendo, Trapper Keeper, and America Online. It was an era of societal reconstruction, and most of the country thought of racism and prejudice as ancient relics, only worthy of a few paragraphs of study during Black History Month, not a current in-your-face injustice. Most white people considered African-Americans equal because we had gained the right to live where we wanted, as long as we could afford it. Some would say it was true, and my parents were living proof.

Their success didn’t make my social life easy, although I didn’t have the problems a lot of black children had. Our refrigerator was always stocked full, our lights were never cut off, and my parents’ cars were never repossessed. Drug addicts in my area were privileged, white teenagers who smoked joints or rifled through their medicine cabinets for pain killers, not the stereotypical black crack heads depicted in the media as lazy midnight burglars hoisting themselves into unlocked windows in the dark of night.

Growing up around kids that didn’t look like me, added to my fragile, teenage insecurities, as did the way some of those kids felt about me. All of them weren’t heinous bullies. A few kids in my neighborhood made me feel welcomed and accepted… most of the time, but not always.

Our school bus picked up many kids from other housing complexes, and those other kids became my problem. By the middle of the first semester I had been called nigger so often that the bus driver didn’t know my real name. When he wanted to speak to me, he would say, “Hey, you.” My tormentors sat in the back and shouted up at me in the front. “I bet you want some fried chicken and watermelon, huh? You black-ass, pucker-lipped mule. Come on back here, and we got some grape soda to wash down your chitterlings. Nigger! I know you hear me, Nigger! Nigger! Nigger! NIG-GER!” Sniggering hissed all around me, even from some kids I considered my friends.

I sat straight with my eyes forward, determined to look dignified, as if what they said didn’t bother me and I was above it, but my bullies were bloodhounds, tracking timidity like fresh game. They never interpreted silence for strength. They rode me, and the bus, to and from school for months, until finally, I could take no more. One day I stood up, ready to confront a boy who regularly addressed me as Tarbaby. Four of his friends stood up to challenge me along with him. I plopped back down and rode home, holding back tears puddled in my eyes as they whooped and laughed at my cowardice.

It didn’t matter if I cried, or fought them, or shouted at the top of my lungs – none of it would have done any good. If those boys dished out brutal beatings, battering my body instead of splashing acidic insults burning me to my core, I wouldn’t have stopped them. I felt too weak.

Unfortunately, I was too embarrassed to tell anyone about the bullying. I didn’t think my parents could stop it, and I knew they wouldn’t try. They were too concerned with their careers and rocky relationship to worry about me being picked on by a few rednecks.

I heard my parents’ arguments, muffled accusations and skirmishes escaping the crack beneath their bedroom door most every night. I sensed their pain like a wild animal senses a hurricane, and like a wild animal, I headed for the hills, fleeing as far away from their storm clouds as possible. I rarely spoke to my mother, and she sought me out only when she received a copy of my failing report card in the mail or if I did something wrong. Because I didn’t think telling them would do any good, I kept my pain concealed behind the outgoing façade of an obedient teenager who was quiet and always did his chores.

In a way, it didn’t matter. Once the school year ended, I didn’t have to worry about those kids anymore. I was free from their torture for a few months, the wounds they had inflicted becoming faint scars, the sting of which I no longer had to endure.

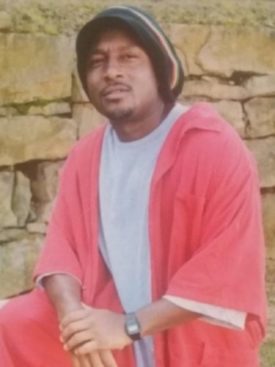

ABOUT THE AUTHOR. Phillip Smith is an accomplished writer, and the above is an excerpt from his autobiography. I hope to be able to share more of it here. Phillip Smith is a student, an advocate, author of NC HB 697, and also editor of The Nash News. His accomplishments are extensive, and he has no intention of slowing down. I am grateful to be able to share his work.

Mr. Smith can be contacted at:

Phillip Vance Smith, II #0643656

Nash Correctional Institution

P.O. Box 247

Phoenix, MD 21131

![]()