I’ve never thought of myself as extra ordinary. Like many born into a family of poverty, I desired more than I’d been shown in my life.

In my family the acme of success was my uncle who’d been hired by the state as a janitor in my grade school. The job came with benefits, union wages, and security. He helped two of his brothers get jobs as well – one of the rare times I’d seen the slow moving man smile.

When people discover I’ve been in prison more than thirty-two years on a ninety year non-homicide sentence – I was seventeen years old at the time – they assume I made some bad decisions. I point out people’s moves in life can only be judged by their options at the time, and their eyes climb their foreheads in shock, as if to say, “Surely, you had better options than to shoot someone!”

On a rare occasion, I’ll see a head tilt to the side, a body’s way of reflecting the brain’s strenuous attempt to see an issue, the world, me? from a different angle.

Sadly, if there is one thing visible in me, it’s my anger. Most people who live in a cage as long as I have come to a place where, for the sake of sanity, a balance has to be struck that allows reason. I’ve always rejected it, that tipping point between the retention of hope, the most valuable of things seen and unseen, on one side and the slow carving off of pieces of myself as I sit on the opposite scale.

Some give chunks of their souls away in an attempt to boost the economy. The more you have, the more you spend, right, hoping it may come back around… Call it karma, or simply planting different seeds in the hope of just a little rain, the effort and sacrifice no less noble because of its desperation or timing. Outside of either, few will lay so much of themselves on the alter for another.

Some toss pieces of self on the fiery blaze of their rage, seeking to stave off the icy bleakness of reality through violence, drugs, and homosexuality, anything to dodge being deprived of human touch and love, the ever thirsty phantoms of hope.

So, my little cousin paroled today with tears in his eyes and a very detailed business plan that I helped him with. I’ve studied for more than fifteen years now, connecting dots of knowledge to create plans that I may never touch myself. I pray I have done all I can to teach him how to do the same for himself. We fought three times before I had his attention, each blow given and received costing me another piece of myself.

I sent him back to a family of poverty, the same one that once set my options before me, but this kid had all the hope that I could give in his pocket. Don’t worry. I’ll find more somewhere… After all, what are any of us worth without it?

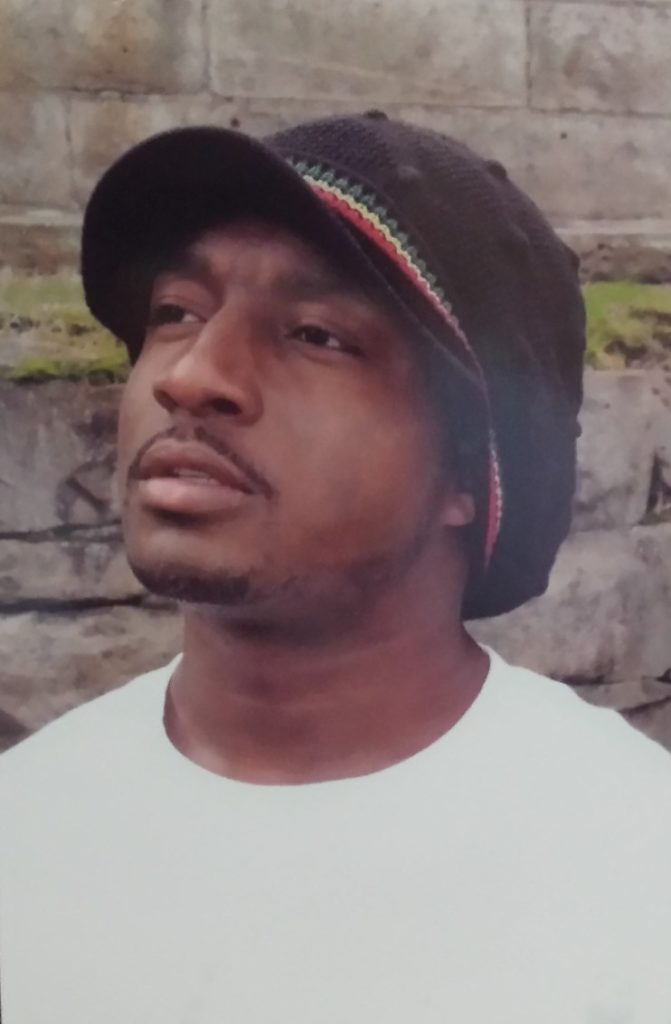

ABOUT THE WRITER. When a gifted writer submits their work to WITS, it is the fuel that keeps this going. Writing that shares the human heart is what we look for, which is exactly what Mr. Jones shared with us. Mr. Jones has served 32 years for a crime he committed when he was seventeen years old. He can be contacted at:

DeLaine Jones #7623482

777 Stanton Blvd.

Ontario, OR 97914

![]()