What happened after the shooting on Lantern Point Drive? Witnesses testified Charles Mamou’s driver left without him. He then jumped in their blue Lexus with Mary Carmouche in the backseat and fled the scene. Mamou has always maintained he followed his driver, Samuel Johnson, back to an apartment complex where he was staying and where the Lexus was found by police with a flat tire. Witnesses have also put Samuel Johnson driving into the parking lot prior to Mamou, although the jury never heard that.

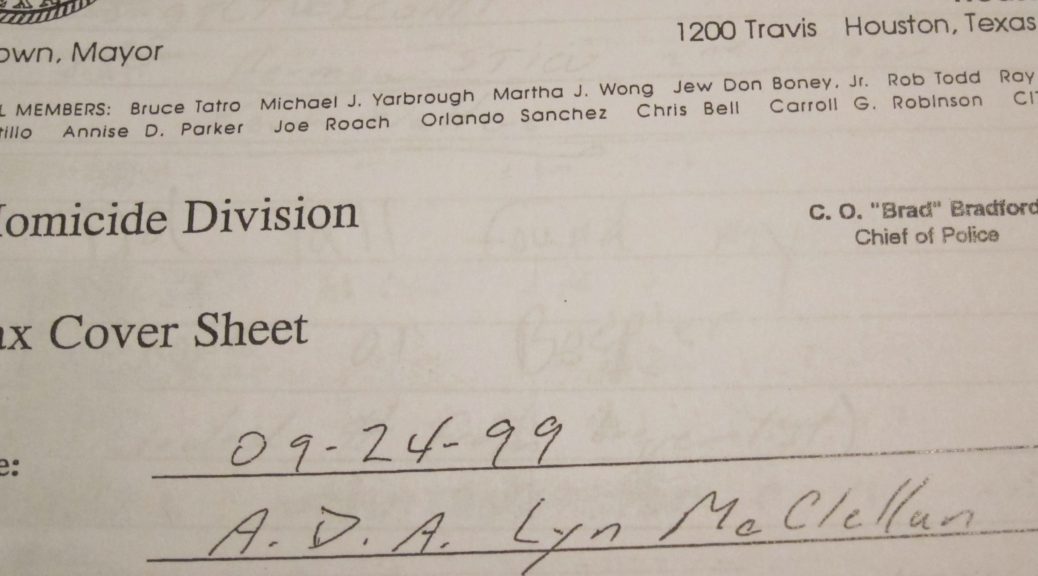

Samuel Johnson supported the D.A.’s version, testifying Mamou drove away from Lantern Point and Johnson simply went home to sleep after the shooting, never speaking to anyone. Contradicting that testimony and unknown to Mamou or the jury, an HPD investigator faxed phone records to the District Attorney’s office indicating Johnson used his cell phone at 2:37 a.m. to call Howard Scott’s apartment – another individual witnessed in the parking lot that night.

Early in the investigation detectives heard the name Shawn Eaglin and were so interested in his involvement, they placed him in a photospread. (HPD Incident Report Supplement 9).

Eaglin’s name surfaced multiple times in witness statements. One witness described investigators going to Eaglin’s home, “Last night while we were at my father-in-law’s house, Shawn Eaglin came to the house. While Shawn was there, we discussed the homicide division coming to my job, my apartment, Ced’s job (Ced is Shawn’s little cousin) and Shawn’s house.”

The witness continued, “At this time, Shawn stated that he needed to check on a friend of his by the name of Bug. I then asked Shawn why did he have to check on Bug [Samuel Johnson]? He never answered why. I asked them who did they know with a red Intrepid car. Shawn started to answer me, but then he said, ‘No, I better not.’”

Detective Novak, in his testimony, referred to Shawn Eaglin as the third individual he was looking at as a ‘potential suspect’.

Q. At a later time did you look for more than one individual other than Mr. Mamou?

A. Yes.

Q. What is that person’s name?

A. We – there was an individual that –

Q. Can you just give me his name?

A. Terrence Dodson.

Q. Other than Terrence Dodson and Mr. Mamou, was there a third individual you were looking at as a potential suspect?

A. Shawn Eaglin.

(Volume 18 of the Reporter’s Record at page 189)

Detective Novak had a thirty year career with HPD at the time. He described Shawn Eaglin as a potential suspect, yet there are no records of any interviews with Eaglin. According to Samuel Johnson’s testimony, Eaglin was responsible for connecting him with Mamou.

Q. Where did you meet him?

A. I met him at a friend of mine’s.

Q. And this friend’s name is what?

A. Shawn Eaglin.

Q. Shawn Eaglin?

A. Right.

(Volume 19 of the Reporter’s Record at page 17)

Q. And where was it that you first met Mr. Mamou?

A. Shawn Eaglin’s home.

Q. And this is the same home that you just referred to as off of West Airport?

A. Right.

Howard Scott, the man who’s apartment Charles Mamou stayed in, was transported to HPD for a statement on Tuesday, December 8, 1998. That statement is not in the Incident file so we may never know what Scott told investigators that day, but Scott also mentioned Eaglin in his testimony.

When asked about the first time he met Mamou,

A. Through a mutual friend.

Q. And that being who?

A. Shawn Eaglin.

(Volume 19 of the Reporter’s Record at page 123)

Q. How long have you known Bug (Samuel Johnson)?

A. Just a few years through – like I said, I met him through the same person, Shawn Eaglin.

Q. Shawn Eaglin?

A. Yes, sir.

(Volume 19 of the Reporter’s Record at page 126)

Q. From between that first time and December 6th, how many other times do you meet him or see him?

A. Just a few other times. Like I said, at Shawn’s house we met. You know, that’s it.

Q. So – and this is before the time that he comes and stays at your house?

A. Yes, sir.

(Volume 19 of the Reporter’s Record at page 132)

Q. So, we get through Friday. Now Saturday, are there people coming over to your apartment while he’s there?

A. Yes, sir, Shawn and, you know, just mutual friends that come over from time to time.

(Volume 19 of the Reporter’s Record at page 139)

Q. You ever meet a fellow by the name of Samuel Johnson?

A. No, sir.

Q. That’s a person they’re referring to as Bug?

A. No, I know Bug.

Q. Did you know Bug before you met Mr. Mamou?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. How you been knowing Bug?

A. Through Shawn, the same person.

(Volume 19 of the Reporter’s Record at page 140)

Specifically describing the night of December 6, 1998, and the apartment complex, Howard Scott testified,

A. We are outside on the front porch.

Q. You said, ‘we’re’. Who is the group?

A. It was me, Ken, Shawn and that’s it.

(Volume 19 of the Reporter’s Record at page 147)

Q. Any discussion going on between you and Shawn?

A. No, sir.

Q. Are you making any comments to any of the people that – your company there – that Chucky and Bug been gone for a long time?

A. No, sir.

(Volume 19 of the Reporter’s Record at page 148)

Scott is specifically asked about his phone.

Q. So are you awoken by telephone calls even after you go to bed?

A. No, sir, no more phone calls. After awhile it wasn’t no more phone calls.

(Volume 19 of the Reporter’s Record at page 149)

Q. Is that because you pulled a plug out of the phone or –

A. No, it just stopped ringing.

(Volume 19 of the Reporter’s Record at page 150)

According to a fax sent to the District Attorney’s office from HPD while the court proceedings were underway, Howard Scott’s phone was ringing that night. That information was not shared with the jury or Charles Mamou.

Howard again refers to Shawn Eaglin being at the apartment complex that night.

Q. Mr. Scott, you talked about Shawn Eaglin being there at your house with his kids for a while, and then he left. When Shawn came back around midnight or a little after, how long did he stay before he left again?

A. I guess about thirty to forty minutes.

Q. So, he left again about 12:00, 12:45 or 1:00 o’clock?

A. Yes, sir.

(Volume 19 of the Reporter’s Record at page 152)

Repeatedly, Shawn Eaglin is placed at the apartment complex that night.

Q. Well, when Shawn is there, I mean, is it right at midnight? It is 1:00 o’clock? Do you know what time it is?

A. I can’t recall the time.

(Volume 19 of the Reporter’s Record at page 153)

Q. So, it could have been anywhere from about midnight to 2:30 in the morning?

A. Yes, sir, could have been.

Q. And when you say he then leaves, do you say good-bye to him at your front door and you close the door and go back to bed?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. So you don’t actually see where he goes to at that point? He’s not inside your apartment?

A. No, sir.

(Volume 19 of the Reporter’s Record at page 153)

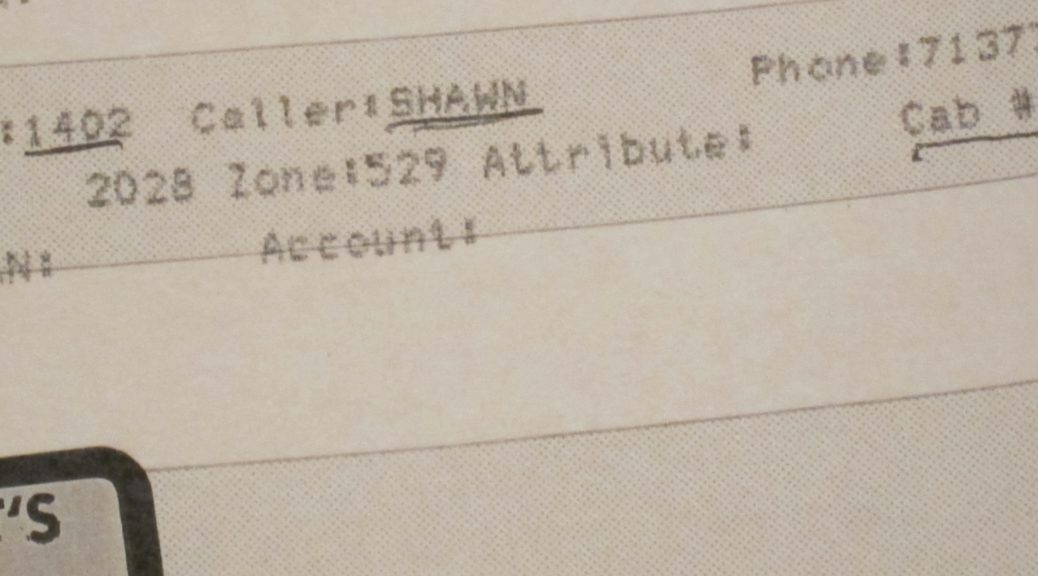

Court testimony wasn’t all that indicated Shawn Eaglin was at the apartment complex that night. A Yellow Cab employee was called to the stand during the trial and questioned about a call the company received that night. As an exhibit, he brought with him a printout from December 6, 1998.

Q. Let me hand back to you Defendant’s Exhibit No. 9. With regard to the call that is reflected at the bottom of that sheet, again, the location where the call was made to the cab driver that went out to a location, what location did he go to?

A. He went to 10800 Fondren.

Q. Was there a particular apartment unit number?

A He was given Apartment Number 1402. (Howard Scott’s apartment number)

Q. And the name of the caller?

A. The caller said his name was Shawn.

(Volume 20 of the Reporter’s Record at page 134)

The prosecutor did his best to discount that testimony and exhibit. He questioned the Yellow Cab employee about many things.

Q. And there is no indication by that record that anybody went to Apartment 1402, is there?

A. No.

Q. In fact, they went to a big box? Isn’t that what there is a notation at the side and—

A. The directions say, yes.

(Volume 20 of the Reporter’s Record at page 136)

Q. Okay. So when a person calls in you don’t know if they’re giving you the apartment number they’re in or they’re just giving you an apartment number?

A. That is true.

(Volume 20 of the Reporter’s Record at page 136)

Q. I understand you assume. Now it says a name there, Shawn. Do you know how many Shawns live over in the 10800 block of Fondren?

A. No, sir.

Q. Do you know who that Shawn is?

A. No.

(Volume 20 of the Reporter’s Record at page 138)

Charles Mamou has maintained he drove the Lexus from the drug deal to the apartment complex. He also said he later saw Shawn Eaglin leave Howard Scott’s apartment and get in a Yellow Cab vehicle. There is very little evidence in this case, but the little there is, is consistent with Mamou’s recollection of events.

The D.A. tried to call into question the reliability of the Yellow Cab report, and even asked about how the phone number was recorded – which turned out to be caller I.D. The prosecutor did not ask the witness about the particular number itself or share what was known about the phone number on the report. The jury never knew, nor did Charles Mamou, that the phone number requesting the cab came from inside Howard and Robin Scott’s apartment, which is consistent with exactly what Charles Mamou said he saw twenty years ago.

The jury was also not told Shawn Eaglin lived five minutes from Howard Scott’s apartment – the exact amount of time the taxi’s meter was running, from 4:04 a.m. until 4:09 a.m.

Harris County dominated the field when it came to racking up death sentences, and Lyn McClellan was an MVP. The case he built against Mamou was built on one man’s statement – a statement investigators knew didn’t match up to actual events and described a confession in a phone call from Louisiana when Mamou was actually in Houston.

It appears anything that contradicted that statement either didn’t make it into the file or was removed, and anything investigators or the D.A. knew that contradicted that statement – was not shared with Mamou or the jury.

The fax HPD sent to the D.A. didn’t just contain a record of Samual Johnson’s calls, it also showed phone calls from Shawn Eaglin.

There is not one record of any interview with Shawn Eaglin in the case file. He was at one time considered a suspect. He was present on the night in question. He was described as talking about investigators going to his home in a witness statement. He had his name on a cab report for a cab ordered from inside Scott’s apartment. He was referred to by almost everyone involved as the party that introduced them all. His name, ‘Shawn’, is handwritten several times in the HPD file. And he was calling Howard Scott as late as 3:12 a.m. on a Sunday night – the jury never heard that.

There comes a point when sloppy record keeping turns a corner…

Like any record of an interview with Howard Scott at HPD on Tuesday, December 8, 1998, there are no records of any interviews with Shawn Eaglin.

Anyone with information regarding this case can contact me at kimberleycarter@verizon.net. Anything you share with me will be confidential.

All related posts detailing all I have learned over the last two years are available at Charles Mamou.

TO CONTACT CHARLES MAMOU:

Charles Mamou #999333

Polunsky Unit 12-CD-53

3872 South FM 350

Livingston, TX 77351

![]()