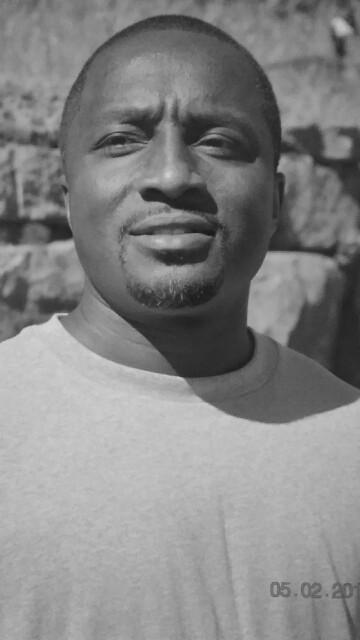

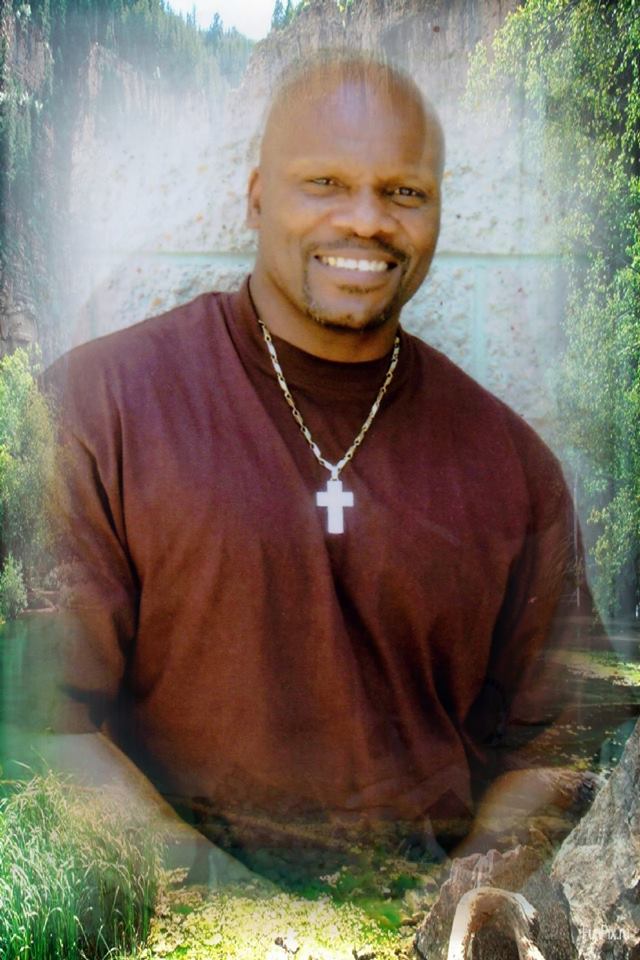

When a person comes up for parole in Alabama, they don’t get a chance to speak for themselves and aren’t present when their fate is decided. A lot is left out of the equation. Some of the reasons for Louis Singleton’s most recent denial – ‘Release will depreciate seriousness of offense or promote disrespect for the law’, ‘Severity of present offense is high’, ‘ORAS level is moderate risk of reoffending’.

What they probably didn’t discuss…

On January 11, 1994, Louis Singleton was seventeen years old and still attending high school when he shot three men in a McDonald’s parking lot, killing one, and paralyzing another. He was sentenced to life – with the possibility of parole. He has since been denied parole four times and has been incarcerated for a quarter century. The Parole Board will revisit his case in January of 2023.

Prior to the shooting, Singleton had been the sort of kid most parents would be proud of. Boys will be boys, but his life was on track and he had positive goals. He had a speeding ticket once because he was driving too fast to get to summer school. He also got in a fight when he was sixteen.

The neighborhood knew Louis as a ‘good kid’ who dreamed of football superstardom. He might not have been the most academically focused, but he had goals and maintaining some standard of education was required, so he towed the line. After his arrest he was evaluated by the Strickland Youth Center, who determined he ‘did not appear to be a behavioral problem’. In the transcripts, he was described as enjoying a ‘favorable reputation within his community’. Louis Singleton wasn’t known as a threat to others then – and he hasn’t been known as a threat to others since his incarceration. He did have a problem at the time though – a threat was pursuing him.

One of Singleton’s close friends, Derrick Conner, was dating another man’s ex-girl. By association, Singleton became a target of that man’s anger. Had it happened today, things would most likely not have gotten as far as they did twenty five years ago.

Over the many months prior to the shooting, Louis Singleton was shot at on several occasions by the ‘ex-boyfriend’, Kendrick Martin, and his friend, Nelson Tucker. On one occasion, Singleton was inside a car when Martin was beating the vehicle with a crow bar. Louis recalls one time when Martin pulled a gun from a book bag and pointed it at his head.

The violence and bullying were no secret. Louis Singleton tried to get it to stop by talking to parents, school officials and even the police. Nothing was resolved, and on that winter night in that parking lot when Louis ran into Kendrick Martin and his friends – no one will ever know exactly what happened, but the boy who had been shot at and pursued for months – shot at those who had been terrorizing him.

But for the months leading up to that night – it never would have happened. Louis Singleton would have continued living his normal, average life. The entire incident is tragic. It’s tragic for the man who died. It’s tragic for the man who will never walk again. And it’s tragic for the seventeen year old kid who didn’t know how to deal with something he should have never had to. The adults who were aware of what was going on not only let Singleton down – but the victims as well.

Louis Singleton has spent a quarter of a century in the brutal Alabama prison system. He lost all his dreams. He lost his youth. He lost his mother and has lived with the regret and memory of having to tell her what he did that night.

Some feel no amount of time will suffice. Forgiveness will never come for those. Remorse has though.

Alabama prisons are barbaric. A typical prison is an inhumane warehouse of people, many dangerous, bodies packed in on top of one another in a sea of bunks, sheets hanging to try and give a semblance of privacy, a random individual laying on the floor at any given moment, having taken whatever they can get their hands on to escape the reality of their nonexistence, and there is not a moment that goes by you aren’t aware you have no value. Your life can be lost in the blink of an eye.

In the southern heat, there is no air conditioning and very limited staff. As someone once told me – the inmates police themselves. In spite of the place he lives, Singleton has not had a disciplinary action that involved violence since 2010, when he got in trouble for ‘Fighting Without A Weapon’.

Before the hearing this year, Singleton was hopeful. The board doesn’t think he’s suffered enough yet though. One look in his eyes would tell them different, but they will never see him. He’s exists only on paper to them. A couple years ago, Singleton shared what happened right after the shooting.

“My mind was racing with thoughts that I couldn’t even grasp mentally. I just went home and sat in the house with all the lights out, scared to move, don’t know what to do nor to say. My mom was gone to a choir convention in Mississippi during the time of the incident. While I sat in our house quietly and somberly in the front room, my mother pulled up with no clue of what just happened. When she came in the door, turned to lock the door, I was sitting there in the dark room. I scared her out of her wits. As a mother who knew her child, she instantly asked me, ‘Boy, what’s wrong with you sitting in here with all the lights out?’ I was so discombobulated I honestly couldn’t speak, it seemed like somebody had my soul…”

Those are the thoughts of a seventeen year old boy – who has suffered enough. The wrong will never be made right, and that seventeen year old boy no longer exists. He’s paid the price. Those who let it get that far never did – but Louis Singleton did. My heart goes out to those who have been touched by this tragedy. More suffering won’t heal that pain.

Would I even be writing this if Louis Singleton had been a promising white high school athlete? I doubt it. The school and authorities would have resolved the issues long before they got to that point.

Louis Singleton can be contacted at:

Louis Singleton #179665 0-24

Donaldson CF

100 Warrior Lane

Bessemer, AL 35023-7299

![]()