When my family and I moved to E. B. Jordan Homes in 1980, it was like a ghost town in the woods – rural, secluded, somewhat lawless and all the perks of country living. There were ditches to scour, trees to climb, fields to rove; and also the not-so-friendly white people to consider. It was the early period of gentrification in Wilson, when underprivileged families were uprooted from the inner city and relocated to areas where we were less welcome.

E.B. Jordan Homes was a project housing community on the outskirts of town between a predominantly white neighborhood and a motorcycle club. We had the n-word flung at us from some few cars passing by, but other than that, it was a great place to live, and my mischief began when I was young. At seven I cussed, bullied and vandalized. I stole candy almost everyday from the old service station across the street. I wasn’t afraid of getting caught, nor was I bothered by the obscenities of some whites, but no matter how tough I acted, I was always scared of one thing… London Church.

That was all I knew about the old creepy church that sat several yards from our front door. It was called London Church. It was faded white with chipped paint and shutters on the windows and guarded by towering oak trees. The older kids told stories about London Church being built atop a cemetery and the funerals for those graves were held inside London Church; that alone kept me up many a night staring over at the church grounds waiting for something to move. I spent the first few years trying to forget all the scary stories I’d heard, but often enough I would pass by London Church and wonder – yet throw a pretty girl in the mix and just like that, I was ready to confront my fears.

It began one day with some silly notion that was caught on the wind. We were hoping to impress some neighborhood girls when someone said, “Let’s break into London Church.” At the time, I associated the name London with England, and I thought of him as some ancient white man, one whose spirit would not take kindly to a bunch of Black kids running around in his church. But then the thunder crackled and the lightning flashed, and the break-in seemed like the perfect thing to do, as though God himself was saying, “I’mma lookout for y’all little bad asses this time, but you owe me one.”

So we headed over to London Church, one foot-step coaxing the other with the acoustics of thunder to incite our false courage. We told tall tales of ghosts and demons and old white slave masters, who would shackle not our bodies but our spirits. When we got there, all the wide-eyed looks turned my way, and unanimously I was elected the scapegoat… so I shimmied open the window and with a boost I climbed inside, in effect breaking into London Church. What happened next is spotty and irrelevant as the events of that day are now but a haze in my distant past, but what I did was dishonorable and has left me with lingering regret as I would come to learn more about the man called London.

On Valentine’s day, 1970, three years before I was born, the Wilson Daily Times published a full-page article on London Woodard, a man who was born a slave, yet died as a pivotal figure in Black history. London was born in 1792, the whip-cracking era when black bodies were deemed no more than chattel in an economy driven by cruelty. A time when Black heritage and Black identities, like the names of London’s parents, were snuffed out of existence and did not survive the passage of time. Much of London’s young life was unknown, but at 24, he was recorded in the estate of Asa Woodard, and later at 34 with Julan Woodard, indicating the familial passing down of his enslavement. On March 22, 1827, just one year later, London would be sold again. He was bought at an auction by Administrator James B. Woodard for $500. London would spend the majority of his adult life on the Woodard plantation as the slaves in those days seldom strayed far from the “good master”. London was 35 when he met another Woodard slave, a woman named Venus, and the two found marital bliss and would remain a union for 18 years, until Venus died in 1845.

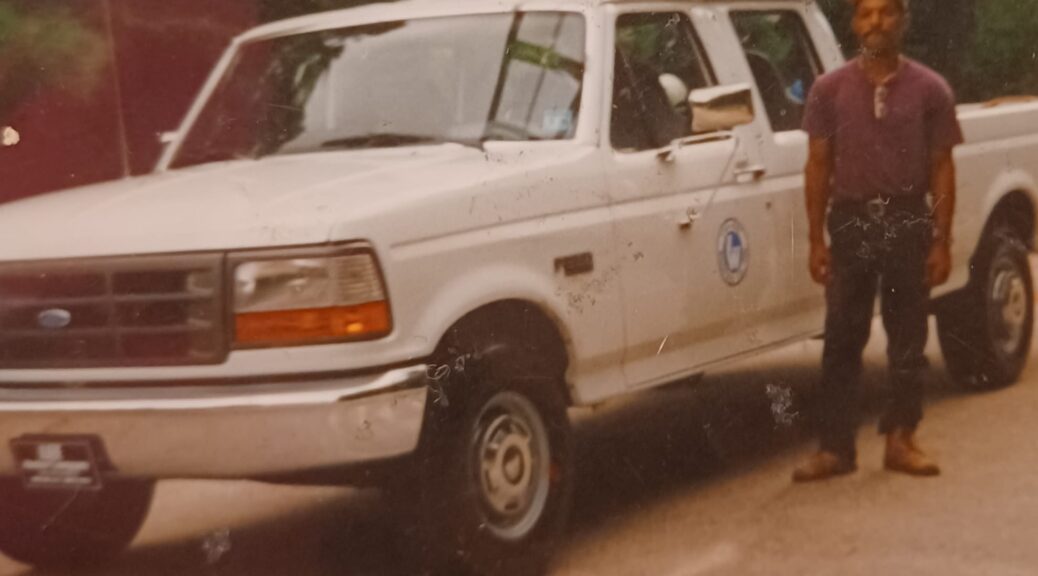

London was recognized as a distiller in fine fruit brandies, providing a euphoria to the other slaves to best deal with the day’s long heat and the lash of the master’s tongue. He was baptized on August 24, 1828, as a member of the Tosneot Baptist Church, a site located some few miles from the E.B. Jordan projects where I grew up and established as the oldest church in Wilson. From there London was promoted to the Overseer, tending to the slaves for the master, a discovery to which I felt indifferent to old London, but unfair since I don’t know what it’s like to be a slave.

It was, in fact, as the Overseer that London caught the eye of Penelope Lassiter, a woman born free in 1814. When she was 29, Penelope was hired as the housekeeper and surrogate mother to the children of James B. Woodard after the death of his second wife. Woodard would again marry 4 years later, but by then Penelope had become vital to the rearing of the children, and so she was kept on as she would come to be known as Aunt Penny. It was while working on the plantation that Penelope’s admiration for London grew, and in 1845, the same year his wife Venus died and London was left with 9 children, he and Penelope married. London was 58. He and Penelope had 6 kids together.

Penelope was born the daughter of Hardy Lassiter, a mulatto who owned a farm south of Wilson. Penny, herself, would prove to be business minded, and at 39, she bought 106 acres (five miles east of Wilson on Tarboro Road) for $242. It was then 1853 and she and London had been married 9 years. The next year, she paid $150 to James B. Woodard and bought London’s freedom.

But freedom would come at a far greater price when enslavement was all that one knew, and London would stay on at the Woodard plantation for another 11 years until he was officially emancipated. He did, however, continue to thrive, and on December 11, 1866, just one year after his emancipation, London bought 200 acres of his own. He also continued in his devout membership at Tosneot Baptist Church until after the Civil War, and on April 22, 1866, he was granted permission to preach amongst his “acquaintances only”.

Elizabeth Farmer, who was also a member of the Tosneot Baptist Church, donated one acre of land for $1 for the purpose of building a Black church. The stipulation was as recorded, “…in the event that said premises be used for secular affairs, either by concord or trustees, then deed was null and void.” London went on to preach in Black homes and other circles of his peers for 4 years, until he was officially licensed to preach and saw the construction of the Black church completed.

London Primitive Baptist Church was opened for service on Saturday, October 22, 1870. It was regarded as the first Black church in Wilson County. London was 78 and unfortunately he would preach at the church for only 3 weeks. His last sermon was on November 13, 1870. The next day he suffered a stroke and fell into an open fireplace. Burned beyond recovery, London lived long enough to dictate a will, leaving his wife Penelope much of his furnishings and equipment, and to his children, his beehives and a tenth of the residue each, valued at $7 a share. He dictated the will before the Woodard brothers (William, James Simms, and Calvin) as witnesses, though London was too weak to sign the will himself. He died the next day, November 15, 1870. His will was attested and probated one week later.

And that was the story of old London Woodard, who was best known as Uncle London. But it was only the beginning of his lasting legacy as his church would stand more than 100 years later.

The history of London Church was declared murky for the next 25 years until it was rebuilt in 1895. It’s new location was on Herring Avenue, some 50 yards from the original site on London Church Road and even less than that from my childhood home. It was recognized under the umbrella of the Turner Swamp Primitive Baptist Church in 1897, and it is still in use today, making it a prestigious landmark for Black spiritual practice.

So that day when I broke into London Church, I broke the seal on something sacred – a place where Black ancestors far and wide once congregated in holy union. I’d passed under the threshold and stood in the halls of an ex-slave and survivor, whose name would now defy the passing of time. And though I’d trodden on the floors of Black excellence, desecrated by my youthful ignorance but made whole I would hope by my earnest accountability, I pray that my egregious offense to Black history and my blundering childhood ways are pardoned by the spirit of Uncle London.

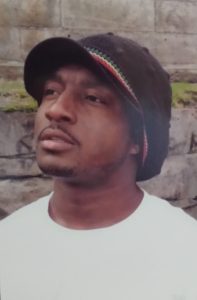

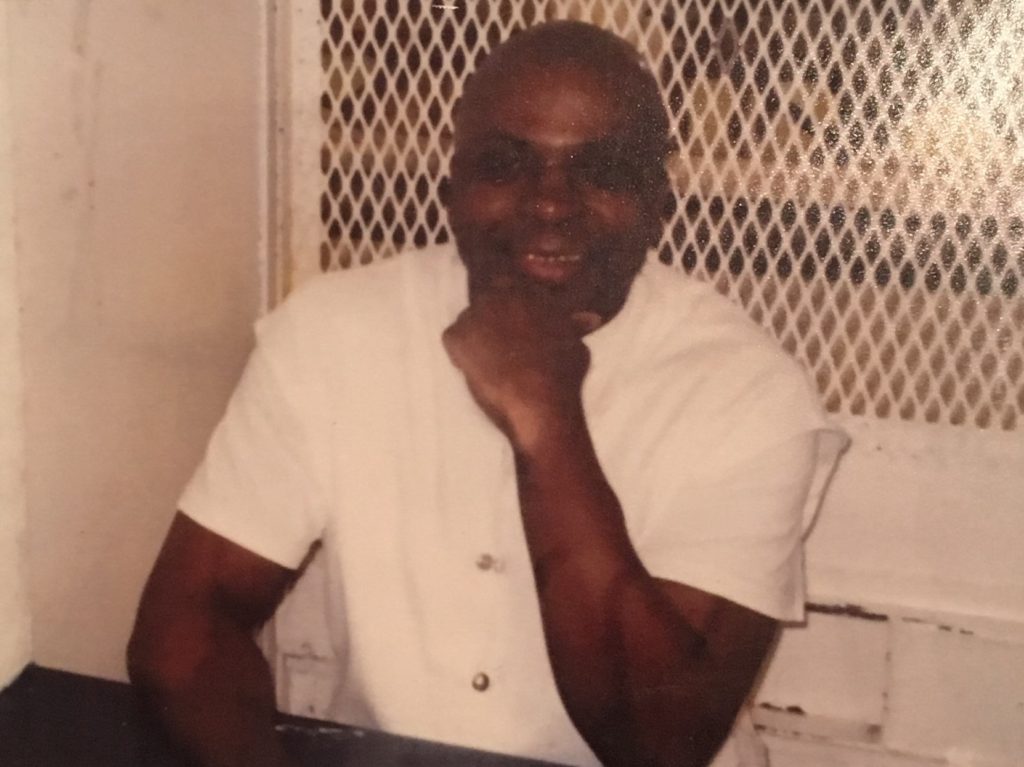

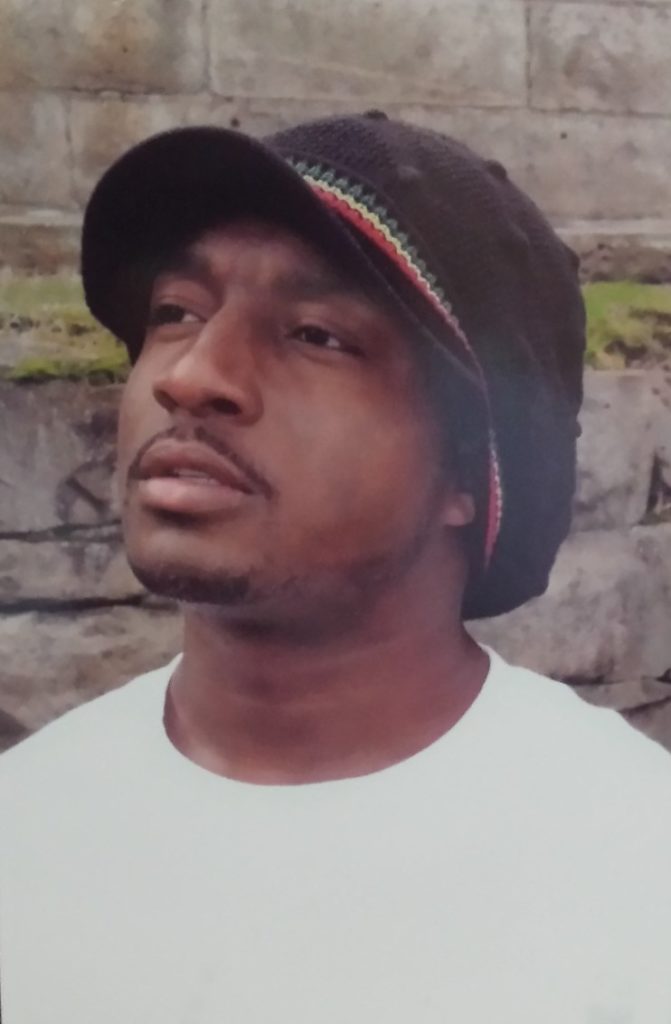

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Terry Robinson writes under the pen name ‘Chanton’, is a member of the Board of Directors of WITS, and heads up a book club on NC’s Death Row. He is currently working on a work of fiction as well as his memoir, and he is co-author of Beneath Our Numbers: A Collaborative Memoir From Inside Mass Incarceration. He has always maintained his innocence, and WITS will continue to share his story and his case.

Terry can be contacted at:

Terry Robinson #0349019

Central Prison

P.O. Box 247

Phoenix, MD 21131

OR

textbehind.com

There is also a Facebook page that is not maintained by Terry, but does share all his work, Terry ‘Duck’ Robinson. Any messages left there for Terry will be forwarded to him.

![]()