October 15, 1999 – it was three days after my best friend, Jeremiah, committed the heinous act of killing three police officers and wounding two others, before taking his own life.

At approximately 2:30 am, while sleeping fitfully on a pallet of couch cushions and blankets on the living room floor at my parents’ home, I was easily awakened by the phone ringing loudly in the other room. I glanced over at Sara, the mother of my son, lying next to me. She stirred in her sleep, as though having a troubling dream. Understandable. The events of the past three days left me quite troubled as well. ‘What the hell was Jeremiah thinking?’ I lament to myself.

At approximately 2:30 am, while sleeping fitfully on a pallet of couch cushions and blankets on the living room floor at my parents’ home, I was easily awakened by the phone ringing loudly in the other room. I glanced over at Sara, the mother of my son, lying next to me. She stirred in her sleep, as though having a troubling dream. Understandable. The events of the past three days left me quite troubled as well. ‘What the hell was Jeremiah thinking?’ I lament to myself.

I feel as though I failed my friend in some way. The news stories about the incident keep flooding my mind – pictures and video of the crime scene; bright yellow police tape everywhere, blocking roads and nearby properties; blood stains on the ground; a police car splattered with blood and riddled with bullet holes; police officers combing the area for evidence; little yellow cones all over the ground marking numerous bullet casings…. I squeeze my eyes shut, and try to think of something else. The phone rings several more times as I lie in the dark with my eyes shut before it stops. Either someone answered it, or whoever was calling hung up.

A minute later I feel someone lightly nudge my shoulder before whispering my name, “Kenny, wake up.” It’s my mom. She’s kneeling next to me with a scared and worried expression on her face, holding the phone out for me. As I reach for it she says in a shaky voice that it’s the police, and they have the house surrounded. I was so damn tired, and now confused. I accepted the phone and slowly stood up. As I look around I see bright lights shining through the curtains in the front and rear of the living room windows. ‘What the fuck is going on?!’ I think to myself. “Hello?”

In a professional, no-nonsense tone, a male voice identifies himself as a Texas Ranger, says he has a warrant for my arrest, the house is surrounded and I need to come out right then, with my hands up. “What? Why? What’s going on?” I ask, bewildered.

“Just come on out, right now, and we’ll explain everything to you. Don’t make us come in and get you,” responds the Ranger.

“Can I at least put some clothes on first?” At this point, I’m wearing nothing but silk boxer shorts.

“No,” replies the Ranger. “Just come on out how you are, and we’ll get your clothes for you. Come out slowly. Do exactly as instructed. If you make any sudden movements, you will be shot.”

‘Holy shit! This is serious!’ I think to myself in a state of disbelief. Now, I am fully awake, my heart beating like it was just injected with a syringe full of adrenaline. Anger begins to mix with the confusion. “Okay,” I respond in a tone that sounds sure and unafraid as I hang up feeling shaky and scared.

Everyone in the house is awake now and watching me. I take a deep breath and quickly struggle into a pair of dark green cargo pants, there is no time to locate my shirt and shoes, while I repeat everything the Ranger said. We are all frightened and in a state of bewilderment. We immediately discuss what to do.

Obviously, I have to comply. They are not going to just go away. Mom says she’ll call an attorney we know, first thing in the morning. I can feel my time running out, so I hug everyone goodbye. First, Dad, with just a quick hug. Then Mom. She embraces me a bit longer and tighter. I can feel her trembling a bit. Finally, Sara. She clings to me like a child clings to their parent on the first day of school – afraid and not wanting to let go. But, alas, it is time to go. We softly kiss one last time. To this day, I can still feel the warm embrace of everyone that ominous night.

My hand shakes slightly as I turn the knob of the front door and pull it open. I turn back to face my family, take a deep, shuttering breath, muster a smile, turn slowly back to the open doorway, and raise my hands up to the sky before I begin my very slow descent down the three front steps.

Little did I know this would be the end of our physical contact for many years to come. Had I known, I would have lingered awhile longer. Hell, I may have even made that Ranger and his goon squad come in and get me! To pry my arms from around my family. Sigh. But I didn’t know. How could I? I didn’t know the so-called justice system would use me as a scapegoat.

There was a light, cool breeze carrying the scent of fall as I descended the steps to my unknown fate. It rustled the hair on my chest and under my arms, giving me goose-bumps. The sight of all the police cars surrounding my parents’ home was staggering. I got the urge to run, like a startled gazelle being chased by a hungry lion. ‘Is this really necessary?’ I thought to myself. Along with the breeze, I detected a faint, foreign smell. ‘What is that?’ I pondered from somewhere in the recesses of my overloaded mind. It did not dawn on me until much later – fear! It was the scent of my own fear. I’ve come to know this scent very intimately throughout the course of my battles with the justice and penal system.

There was one officer standing slightly in front of all the others, as though he was the one in charge. The bright headlights pointing at me from all the police cars, made it difficult to make out any details. As I turned to him, he told me to keep my hands up and walk towards him very slowly. The grass beneath my feet felt cool, soft, and wet from the dew beginning to cover it. But that didn’t fool me, as I knew that grass was notorious for producing some pretty nasty stickers. I proceeded with caution.

There was one officer standing slightly in front of all the others, as though he was the one in charge. The bright headlights pointing at me from all the police cars, made it difficult to make out any details. As I turned to him, he told me to keep my hands up and walk towards him very slowly. The grass beneath my feet felt cool, soft, and wet from the dew beginning to cover it. But that didn’t fool me, as I knew that grass was notorious for producing some pretty nasty stickers. I proceeded with caution.

When I reached about halfway to the lead officer he told me to stop, turn around, and walk backwards the rest of the way to him. Slowly. ‘Seriously!? What is this guy’s problem!’ I wondered to myself.

As soon as I began my backwards walk, I stepped on a damn sticker. Shit, that hurt! I had to fight my instinct to reach down and pull the offending sticker out of my foot. That might be construed as a “sudden movement”, and therefore an excuse to shoot me. I wouldn’t give them that pleasure. So I forced myself to keep going, hoping like hell I wouldn’t step on any more.

I was told to stop again. When I did, I was immediately surrounded by officers with hate written all over their faces pointing their guns at my head and chest. The lead officer harshly grabbed my hands, one at a time, twisting them down to my lower back, and snapping cold, steel handcuffs on my wrists. Click, click, click – left wrist. Click, click, click – right wrist. There is something about being handcuffed that’s very unnerving. It’s a feeling like no other. A feeling of doom. Of finality…

The lead officer roughly searched my pants for weapons. When none were found, he guided me with an iron grip by my neck and cuffed hands to the already open back door of his patrol car, before shoving me, not so gently, onto the cold, hard back seat. “Hey, watch it asshole!” I instinctively blurt out. He just smirks and slams the door shut.

I took that time to brush the sticker out from the bottom of my foot, using the toe of my other foot. Ah…that felt better, especially as I massaged the puncture area with my toe. The lead officer got into the driver’s seat, and another officer filled the passenger seat. Both put their seatbelts on. Police jargon was spoken into a police radio by the lead officer. He received a similar response within seconds, and then we were off. A few patrol cars went first. We took the middle, followed by who knows how many behind us. They were all driving well over the posted speed limit, even around corners. All I could make out was taillights and headlights, and the roar of all the engines reminding me of being at a car race. Since the lead officer didn’t bother to buckle me in, I was able to entertain him by roughly sliding around at each turn on the cramped, tan colored, hard plastic seat that smelled heavily of disinfectant. I caught his damn smirk looking at me several times through the rear-view mirror. After about 25 minutes, which felt like hours, we arrived at the County Jail.

To be continued…

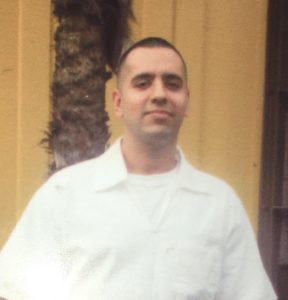

ABOUT THE AUTHOR. Kenneth-Conrad Vodochodsky is a gifted writer, serving a 30-year sentence in Texas, based on the “Law of Parties”. He can be contacted at:

ABOUT THE AUTHOR. Kenneth-Conrad Vodochodsky is a gifted writer, serving a 30-year sentence in Texas, based on the “Law of Parties”. He can be contacted at:

Kenneth-Conrad Vodochodsky

#01362329 – Pack 1 Unit

2400 Wallace Pack Road

Navasota, TX 77868

![]()

Days turned into weeks – weeks turned into months. Finally, the day came when he asked me, “Darrell, do you think that I can write good enough to send my dad a letter?” Without saying a word I slid him a blank piece of paper and handed him a pen. As I sat and watched, he painstakingly printed on the paper…

Days turned into weeks – weeks turned into months. Finally, the day came when he asked me, “Darrell, do you think that I can write good enough to send my dad a letter?” Without saying a word I slid him a blank piece of paper and handed him a pen. As I sat and watched, he painstakingly printed on the paper…

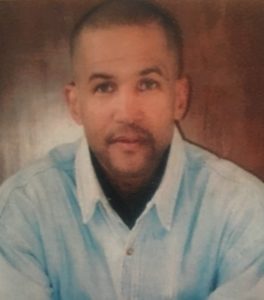

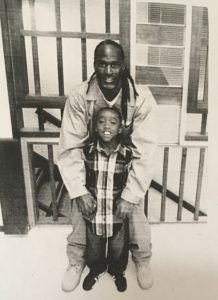

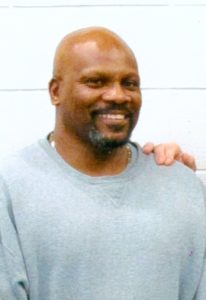

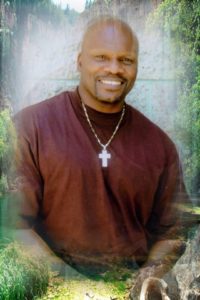

This is Ernest Parker, proud father and grandfather. His warmth runs deeper than the smile. His friends speak of him fondly, and I recently had the privilege of reading a letter he wrote, in which he described a fellow inmate. Of his friend, he said, “His smile is like a beacon of light shining in the valley of despair.” While speaking so highly of his friend, Ernest Parker also described his home as the ‘valley of despair’. His home of nearly three decades has been a federal prison.

This is Ernest Parker, proud father and grandfather. His warmth runs deeper than the smile. His friends speak of him fondly, and I recently had the privilege of reading a letter he wrote, in which he described a fellow inmate. Of his friend, he said, “His smile is like a beacon of light shining in the valley of despair.” While speaking so highly of his friend, Ernest Parker also described his home as the ‘valley of despair’. His home of nearly three decades has been a federal prison.

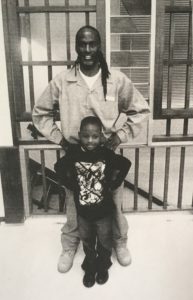

Yet, Robert Booker remains in prison to this day. He is serving his time as a trusted inmate, walking the halls of what used to be a college campus in Yankton and watching the geese fly by. He continues to miss all of the ‘firsts’ with his grandkids, walking in endless circles around a track, and writing. And the government continues to fund his incarceration in order to punish a man who has already been punished, reform a man who has already been reformed, and keep a man they know is not a threat to anyone far removed from those who love him. For what? Robert Booker is the face of the fallout of the failed war on drugs.

Yet, Robert Booker remains in prison to this day. He is serving his time as a trusted inmate, walking the halls of what used to be a college campus in Yankton and watching the geese fly by. He continues to miss all of the ‘firsts’ with his grandkids, walking in endless circles around a track, and writing. And the government continues to fund his incarceration in order to punish a man who has already been punished, reform a man who has already been reformed, and keep a man they know is not a threat to anyone far removed from those who love him. For what? Robert Booker is the face of the fallout of the failed war on drugs. When my family moved to Texas, we had only been there a week when it became apparent I was so lucky to have been raised in such a diverse environment. My dad and I drove from our home in the countryside to a small East Texas town to pick up construction material and a few groceries. On the way out of town, we stopped at a grocery store. It was one of those old country stores – small, well lit, clean. It had the smell of fresh bread baking and home.

When my family moved to Texas, we had only been there a week when it became apparent I was so lucky to have been raised in such a diverse environment. My dad and I drove from our home in the countryside to a small East Texas town to pick up construction material and a few groceries. On the way out of town, we stopped at a grocery store. It was one of those old country stores – small, well lit, clean. It had the smell of fresh bread baking and home. I don’t understand why people treat others differently because of the color of their skin or their religion. When I read Andre’s story, I cried – especially when I saw him standing there with that big smile and his arms around his family.

I don’t understand why people treat others differently because of the color of their skin or their religion. When I read Andre’s story, I cried – especially when I saw him standing there with that big smile and his arms around his family. There he sat, surrounded by Rocket haters, watching Houston destroy Orlando in four games – a sweep. I’ve watched and loved the Rockets since I was eight years old. My Uncle Mike was stationed in San Diego at the time, and he took me to my first pro basketball game. In their first two seasons, they were the San Diego Rockets, and they moved to Houston in 1970. I’ve been a Houston Rockets fan ever since.

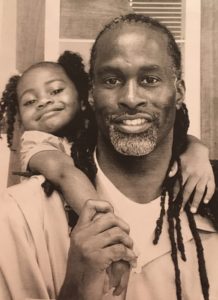

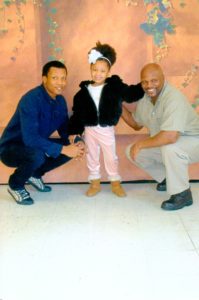

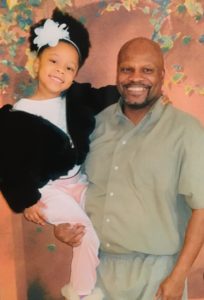

There he sat, surrounded by Rocket haters, watching Houston destroy Orlando in four games – a sweep. I’ve watched and loved the Rockets since I was eight years old. My Uncle Mike was stationed in San Diego at the time, and he took me to my first pro basketball game. In their first two seasons, they were the San Diego Rockets, and they moved to Houston in 1970. I’ve been a Houston Rockets fan ever since. Twenty four years ago, I had four kids, my youngest a newborn son. Now that son has a newborn of his own and a beautiful five year old daughter. He brought her to visit me this past weekend. She proved to me she could count all the way up to fifty before she bit into her corndog. She hadn’t even finished if before she was asking to go to the playroom with the other kids. When my son told her she had to finish her food first, she killed it. I washed up her hands and mouth before she hopped down, ready to go.

Twenty four years ago, I had four kids, my youngest a newborn son. Now that son has a newborn of his own and a beautiful five year old daughter. He brought her to visit me this past weekend. She proved to me she could count all the way up to fifty before she bit into her corndog. She hadn’t even finished if before she was asking to go to the playroom with the other kids. When my son told her she had to finish her food first, she killed it. I washed up her hands and mouth before she hopped down, ready to go. Robert Booker was born and raised in Detroit, Michigan, but has spent nearly twenty-five years in federal prison. He is the author of Push, Tony Jones, The Janitor, Tales From The Yard: Volume One, and Who Is Karma?

Robert Booker was born and raised in Detroit, Michigan, but has spent nearly twenty-five years in federal prison. He is the author of Push, Tony Jones, The Janitor, Tales From The Yard: Volume One, and Who Is Karma?